WYSTAN AUDEN WAS A SWEETIE'

Alasdair Palmer interviews Jack Hewit,

who was once, among other things, Guy Burgess's lover

`A WOMAN once swore to me that I was a Wykehamist. She was absolutely certain. The funny thing is, not long before, Guy put me in an Eton tie, and everyone swore I'd been to Eton.' Guy' was Guy Burgess, then Hewit's lover. The memory still makes Jack Hewit chuckle. Born 77 years ago to a working-class family in Gateshead, in a two-bedroom apartment with no bathroom, no electricity and an outside lavatory, he ran away from home at 15 after being told by his father that as soon as he finished school he would be down the pit or appren- ticed to be a plumber. `My childhood was about as far from Eton or Winchester as it's possible to imagine,' he says in impec- cably plummy tones.

During his life, Jack Hewit has zig- zagged his way across most of the barriers in the English class system, from the high- est to the lowest and the most solidly mid- dle. He can drop instantly from cut-glass English into pure Geordie whenever he feels like it. Where does he think he belongs now? `I'm not sure I belong any- where,' he says, smiling faintly.

When Jack Hewit arrived in London in 1932, he was a lithe northerner speaking with a thick Geordie accent. `All I wanted was to be a dancer. It wasn't the kind of thing you could do in Gateshead. I walked out of the house wearing two suits because I didn't want anyone seeing me leaving with a bag of clothes.' He slept rough for a couple of nights, then got a job in a Bayswater hotel as a page-boy. But he knew that if he wanted to get anywhere he would have to change his accent. 'So one day I said to the hotel's manageress, "Madam, where can I learn to talk like you?" She laughed, then gave me the name of an elocution teacher.'

Hewit pursued his aspiration to learn upper-crust English with undiluted deter- mination. His elocution teacher told him he'd have to have two of his back teeth removed if he was ever going to flatten his tongue sufficiently to bring out words like `count' properly. "'Count" is a difficult word. Lots of people from lower-class backgrounds have trouble with it . . . Edward Heath, for example. He can't say the word "count". He tries, but it comes out sounding like "ceeount", which is horri- ble.' Hewit had his two teeth removed, and has had no problems with enunciation since. But it wasn't his accent which elevat- ed him from the below-stairs world of hotel service. It was his sexuality.

`There was an enormously vibrant gay world in London in the Thirties. It may seem surprising, but there were scores of gay clubs then. You could meet some very interesting people. I remember Sir Paul Latham, Conservative MP for Scarbor- ough. He was a family man, but his inclina- tions were not heterosexual.' Sir Paul invit- ed Hewit to his family seat for a weekend, arriving in a Rolls-Royce to pick Hewit up. The weekend was not an unqualified suc- cess. `He had an artificial leg. How I stopped myself from giggling I'll never know,' Hewit recalls, giggling uncontrol- lably as if to make up for stifling his laugh- ter at the time. It goes without saying that Sir Paul was taking huge risks. `It wasn't just that homosexuality was illegal. It was also that I was still a minor — under six- teen. You can imagine what would happen if the Sun got hold of that now. But I doubt if anyone can imagine the scale of the scan- dal if such a thing had come out in 1932.' Then — as now — Sir Paul Latham was not the only Conservative politician willing to live dangerously in order to satisfy his sexual preferences. `I could name plenty of others, but I don't want to. They have fami- lies who might not know. No, it's not right that they should discover what their grand- father got up to by reading a copy of The Spectator.'

Hewit sounds a little like an old spymas- ter refusing to reveal the names of his agents. But then he spent ten years with Guy Burgess, the wildest, if not the most successful, of the Cambridge spies. `I met this Hungarian man in a bar,' Hewit recalls. `He asked me if I wanted to go to a party. I said yes, thinking I might get some food there.' The location of the gay party turned out to be the War Office. `And that's where I met Guy.'

Hewit moved in with Burgess soon after- wards. Burgess's way of life was something of a surprise. `He would get up, chew a clove of garlic. He'd have breakfast at the Reform Club, which would consist of a double port and a double brandy. Then he'd saunter off to the Foreign Office to read Top Secret documents.' And then he'd pass them on to the Russians.

Burgess knew most of literary London. And so, after a time, did Jack Hewit. spent a weekend in Brussels with Christo- pher Isherwood. Wystan Auden was a sweetie. E.M. Forster was delightful, a kind, gentle and humane man. Maynard Keynes and Benjamin Britten I liked too. I didn't care for Victor Rothschild. He was rich enough to be very dangerous. And he lied about many things. And then there was Anthony, of course . . . "Anthony' was Anthony Blunt, who lived with Hewit and Burgess during the war. 'Anthony was very well connected. He faded beautifully into the royal background. He was very good friends with Queen Mary. One Christmas, she sent him a present with a note written in her own hand: "Dear Mr Blunt, I do hope this reticule will prove useful."' It is hard to know what would have shocked Queen Mary more: Blunt's spying or his time in gay bars. 'Actually, Anthony didn't really like gay bars that much,' adds Hewit quickly. `He preferred contemplat- ing Poussin.' Like Queen Mary, Hewit knew nothing of Burgess's and Blunt's secret work for the Russians, or even of their pro-Soviet sympathies. 'The only time I got an idea of it was when the three of us went to the first performance of Shostakovich's Leningrad Symphony. Guy was in floods of tears. For a tone-deaf, cloth-eared brute like him, that was remarkable. I suddenly thought: he really cares about what this stands for.' What about socialism? 'Guy made a couple of attempts to talk to me about it. I told him that the only people who could afford to be socialists were rich people like him. He just laughed.' Hewit had lost his proletarian origins, his Geordie accent and Geordie friends. But he never felt completely at home with the 'Tony Boys', his generic term for Eto- nians and other products of the English public- school system. 'They were almost never rude or unpleasant. And yet . . . I was never really part of that life. They were so confident in their stature, and I was so desperately unsure of mine. When Guy escaped, suddenly, to Russia, they all dropped me. I returned home to the flat and found everything had gone except my clothes. It was beautifully done. But it hurt.' Burgess's disappearance was as big a shock to Hewit as it was to MI6. His eyes still moisten in recalling it. 'I never saw him again. I had one letter saying I should go and see Anthony if I needed anything. But that was it. Finish.'

Hewit decided to rejoin the army, essen- tially because it would ensure that he was anonymous. 'They sent me to Colchester and made me a bombardier. Then one morning I walked into the Naafi and picked up a copy of the Daily Mirror. There was my picture on the front page with the headline "Have you seen this man?" The news was my connection to Burgess, and some insinuations that I could be a dangerous spy. I was immedi- ately summoned to the War Office. I went in a corporal, and came out a civilian. It was that or going to Korea.'

Hewit has no bitterness about the fact that Blunt, who was suspected of spying from the moment Burgess fled, was not merely protected but promoted: he was allowed to take up an appointment as sur- veyor of the Queen's pictures, and no one outside MI6 knew anything of the suspi- cions of his treachery. And even when MI6 had irrefutable proof that Blunt had been a traitor, and Blunt himself confessed to it in 1963, the scandal was hushed up for 16 years. Indeed, it would never have come to light had not an enterprising journalist unearthed it in 1979.

Hewit's fortunes were very different. He was thought to have been only an entirely innocent bystander to the Tony Boys' treachery. But no official attempt whatever was made to protect him. He was left to face the full glare of publicity on his own, and twice had to resign jobs in the Fifties because of it. 'Anthony had powerful friends,' Hewit says calmly, 'and I had none.' So whilst Blunt continued to advise the Queen and enjoy banquets in Whitehall and Buckingham Palace, Hewit was pound- ing the pavement in the rain in search of a job. He eventually .landed one with the Inland Revenue. 'I started as a clerical assistant, which is the lowest form of life.' It was quite a change from parties with Guy at the War Office and the Reform Club. But he stayed with the Tax Office, filling in forms and checking files, until his retirement in 1977.

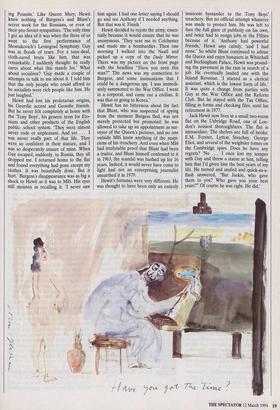

Jack Hewit now lives in a small two-room flat on the Uxbridge Road, one of Lon- don's noisiest thoroughfares. The flat is immaculate. The shelves are full of books: E.M. Forster, Lytton Strachey, George Eliot, and several of the weightier tomes on the Cambridge spies. Does he have any regrets? 'No . . . I once lost my temper with Guy and threw a statue at him, telling him that I'd given him the best years of my life. He turned and smiled and quick-as-a- flash answered, "But Jackie, who gave them to you? Who gave you your best years?" Of course he was right. He did.'

Previous page

Previous page