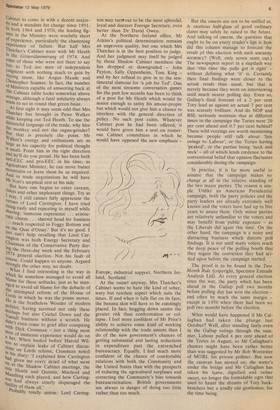

Mrs Thatcher's triumph

Ferdinand Mount

The unacceptable face of Toryism was quick to surface. It was still midafternoon on polling day when I saw a tall man of some fifty summers come out of Claridge's and begin shouting at the traffic. He was good-looking by oldfashioned standards,, like a morose Jack Buchanan, and 4, %%ire a blue pinstripe suit of antique Cie cut. At first, it seemed he was hailing a taxi, declining the service of the hotel doorman out of meanness or high spirits, but as he went on it became clear that what he was shouting and shouting with extraordinary force was 'If you odds and sods know what's good for you, you'll get off your arses and vote Con-serv-at-ive.' Who was this spectre of the '60s? A retired asset-stripper up from Weybridge for lunch with his accountant? A cashiered fringe banker prematurely celebrating the return of the bad old days?

Yet outside the antediluvian swamps of Mayfair and St James's, what jubilation there was remained muted and sober. There was never a more disenchanted victory. The moment the size of the Tory swing was known, the doubts began, not least among those hundreds of thousands who had voted Conservative for the first time in their lives. Would the unions allow Mrs Thatcher to govern? Would the promised tax cuts be blown in betting shops and strip clubs, instead of fructifying in the pockets of the people? Would investors once again be fatally attracted to the hustlers and twisters? Was there any way of bridging the growing gulf between North and South? Did the British people as a whole have any stuffing left in them? Could any government muster the zest to halt the de-industrialising of Britain? Was this to be yet another false dawn, a surrender to a fresh set of illusions?

This wary reaction is partly the legacy of the successive convulsions of failure, partly the legacy of Mr Callaghan's scepticism, for nobody has taught us better than our late and now lamented Prime Minister to distrust the pretensions of government and to expect little and receive less. And it is precisely this atmosphere which favours an incoming government dedicated to reducing its own role — in contrast to 1970, when people still believed that governments could cure economic ills without unpleasant sideeffects.

But it is just as important to see straight as to lower our expectations. It was a famous victory, the greatest swing since the 1945 general election (and the 1945 swing was exaggerated because there had been no election for ten years). This time, a party which had been divided, dispirited and bereft of policy or purpose and which had recorded in October 1974 its lowest percentage of the popular vote in living memory, has been returned to power within five years with a comfortable majority, a huge popular vote and a clear sense of direction. The Tories won over three million votes more than they had in October 1974. Had the constituency boundaries not been biased against them, they would have had a majority of nearer 100. And the percentage increase in their vote was much more evenly spread across the country than the poormouths have admitted, ranging from 9.3 in the South and West, 8.6 in Greater London, 8.8 in Wales, to 7.5 in East Anglia, 7.0 in the North and 6.7 in Scotland.

And if it is wrong to minimise the scale of the victory, it is even worse to trivialise the reasons for it. The feeling that 'it is time for a change' was neither vague nor unthought-out. There is no doubt that a great number of voters identified strongly with Mrs Thatcher's policies; and that is why it is indisputably her victory, not because she is charming or popular or a persuasive speaker but because people want what she wants.

Mr Callaghan and his colleagues are now consoling themselves with the explanation that 'it was all Moss's fault'. As the voters stepped inside the polling booths, they were suddenly reminded of the lorry-drivers with axe-handles, the rats in Leicester Square and all the other horrors of last winter. Had it not been for the bloody-mindedness of the union leaders and their failure to restrain their members for a few more months, we are told, Labour would have been saved.

This is a shallow and dangerous delusion. The revulsion against the Labour government goes back further and deeper. The by-elections have shown a strong and steady swing to the Tories for about three years. Concordats are not enough. People expect more of their governments than the ability to pay hush money in a dignified and timely manner. The Labour Party must not conceal from itself its failure to identify Labour with any of the modern popular causes: lower taxation, home ownership, choice and quality in education. People wish to be what they call 'free'. And Mrs Thatcher is the only British politician, not just in this election but for a long time, who has been able to talk about freedom without embarrassment or ambiguity. She may grate upon refined susceptibilities, but voters know what she is talking about. She dominates this Parliament, not because she fought a dazzling campaign -she didn't — but because she has singlehandedly wrenched Conservative policy, against the instincts of a consensual shadow cabinet, in the direction of an individualist and populist Toryism. On the eve of the poll she quoted Andre Gide: 'All this has been said before but it's so important that it must be said again.' She may have called him Gheed, but how often is the old pederast quoted in Finchley anyway? And what matters is that she did say it again — and again and again, until there could scarcelY be anybody in Britain who was ignorant of the fact that she stands for less guyernment and lower taxes and for peoPle 'standing on their own two feet'. This clarity, this emphaticness is valuable In itself, for one of the things that have weakened the public faith in politics Is the predominance of convictionless, wind-blown politicians. Here is somebuclY, who believes in something or a set 01 somethings and who by her very comae' tion liberates her opponents to think and talk about the things that they believe. Whether Margaret Thatcher succeeds or fails as Prime Minister, there can be lie doubt that as leader of the opposition she has gingered up the argument. Will she succeed? Easily the most Sinificant appointment to her Cabinet Is that of Mr John Biffen as Chief Secret to the Treasury. Mr Biffen is the resigni ing type; he abandons office easily and I he thinks the government is printing tir spending too much money, he'll be ?III before you can say 'minimum lending rate'. At the same time, Mr Nigel Lawson, the No 3 in the Treasury team, Carl be relied on to expostulate volubly at 3,1 sign of financial imprudence. Not "la, anyone doubts that Geoffrey 140`ve„s, heart is in the right place; he has a I W a2.; been a secret monetarist; but among many amiable qualities is a preference fni the quiet life. To those like Mr Enoch Powell Iv° continue to argue that the new govern.ment will perform a U-turn within 51/4 months, one can only say thatthis.Par ticular Treasury triad — Howe, Differ); Lawson — is the most economically ht,e' ate Treasury team since the resignil triad of Thorneycroft, Birch and Powe t tha. himself. And it is important to note she has placed another triad of sr!: pathisers in the industrial department'', Keith Joseph at Industry, John Nott ha; Trade and David Howell at EnergY. S has carefully kept the paternalist silm sidisers and interveners well away fre s the economic departments. The soft egt — Whitelaw, Carlisle, Jenkin — are a engaged on humane missions. this But the best thing to be said about ed Cabinet is that it is the most experiefic Cabinet to come in with a decent majority and a mandate for change since 1951. In both 1964 and 1970, the leading figures in the Ministry were woefully short of experience, particularly the chastening experience of failure. But half Mrs Thatcher's Cabinet were with Mr Heath in the GOtterdiimmerung of 1974. And sonic of those who were not there to say b.00 to Ted are men of independent Judgment with nothing much to gain by staying mum, like Angus Maude and Christopher Soames. In fact, the number Of Ministers capable of answering back at this Cabinet table looks somewhat above average, although a fatal solidarity always tends to set in round that green baize. At first sight it may seem odd that Mrs Thatcher has brought in Peter Walker While keeping out Ted Heath. To use the distasteful language of the trade, why hire the monkey and not the organ-grinder? But that is precisely the point. Mr Walker's energy and enthusiasm are as i.arge as his capacity for political thought is small. Point him in the right direction and he'll do you proud. He has been both anti-EEC and pro-EEC in his time; as Agriculture Minister, he can move butter mountains or leave them be as required. And in trade negotiations he will have Mr Nott's sceptical zest at his side. . but here one begins to enter caveats, riders and other unpleasant things. Try as 1.May, I still cannot fully appreciate the vn-tues of Lord Carrington. I have tried using early and repeating to myself while shaving: 'immense experience ... aristoc ratic charm ... shrewd head for business ' • much respected in Foggy Bottom and 90 the Quai d'Orsay.' But it's no good. I Just can't help recalling that Lord Carrington was both Energy Secretary and C. hairrnan of the Conservative Party during the three-day week and the February 1974 general election. Not his fault of Course. Could happen to anyone. Argued stroll „1.. s. y the other way, no doubt. What I find interesting is the way in ,W,Ineh he somehow managed to avoid all °lame for these setbacks, just as he managed to avoid all blame for the debacle of the attempted reform of the House of Lords in which he was the prime mover. lie. is the Scatheless Wonder of modern Pn.litics, having survived not only these rn_ishaps but also Crichel Down and the y.assall business without a scratch. He al.dn't even come to grief after conspiring With Dick Crossman — not a thing most in en of immense experience would do on a bet. When hauled before Harold Wilsnd to explain leaks of Cabinet discus 00 Lords reform, Crossman noted his diary: 'I explained how Carrington n_ad given me every detail of what went r°11 at the Shadow Cabinet meetings, the “nle Heath and Quintin, Macleod and !vlaudling each played, and how Caningtun. had always utterly disparaged the futility of them all.' Probably totally untrue. Lord Carring ton may turttout to be the most splendid, loyal and discreet Foreign Secretary, even better than Dr David Owen.

At the Northern Ireland office, Mr Atkins's political determination remains an unproven quality, but one which Mrs Thatcher is in the best position to judge. And her judgment may itself be judged by those Shadow Cabinet members she has dropped or downgraded — John Peyton, Sally Oppenheim, Tom King — and by her refusal to give in to the sentimental clamour for 'a job for Ted'. One of the most tiresome conversation games for the past few months has been to think of a post for Mr Heath which would be senior enough to satisy his amour-propre but which would not give him a chance to interfere with the general direction of .policy. No such post exists. Whatever Cabinet post he had been offered, it would have given him a seat on numerous Cabinet committees in which he would have opposed the new emphasis — Europe, industrial support, Northern Ireland, Scotland.

At the outset anyway, Mrs Thatcher's Cabinet seems to have the kind of sober, wary but resolute aspect which suits the times. If and when it falls flat on its face, the banana skin will have to be cunningly placed. In fact, bogging down seems the greater risk than confrontation or collapse. I feel more confident of Mr Prior's ability to achieve some kind of working relationship with the trade unions than I do of the new government's chances of getting substantial and lasting reductions in expenditure past the entrenched bureaucracy. Equally, I feel much more confident of the chance of comfortable relations with both the Community and the United States than with the prospects of reducing the agricultural surpluses and correcting the Community's bias towards bureaucratisation. British governments are always in danger of doing too little rather than too much. But the omens are not to be sniffed at. A cautious half-glass of good ordinary claret may safely be raised to the future.

And talking of omens, the question that ought to be on every reader's lips is how did this column manage to forecast the result of this election with such uncanny accuracy? (Well, only seven seats out.) The newspapers report in a slapdash way that 'this time the polls got it right' — without .defining what 'it' is. Certainly their final findings were closer to the actual result than usual, but that is merely because they went on interviewing until much nearer polling day. Even so, Gallup's final forecast of a 2 per cent Tory lead as against an actual 7 per cent was scarcely brilliant. And do NO? and RSL seriously maintain that at different times in the campaign the Tories were 20 per cent ahead and 0.7 per cent behind? These wild veerings are worth mentioning because people still talk about 'late swings to Labour', or the Tories having 'peaked', or the parties being 'neck and neck' — all of which lends credence to the conventional belief that opinion fluctuates considerably during the campaign.

In practice, it is far more useful to assume that the campaign makes no change at all in the relative standing of the two major parties. The reason is simple. Unlike an American Presidential campaign, both the party policies and the party leaders are already extremely well known and the voters have had up to five years to assess them. Only minor parties are relatively unfamiliar to the voters and may benefit from public exposure — as the Liberals did again this time. On the other hand, the campaign is a noisy and distracting business which distorts poll findings. It is not until many voters reach the deep peace of the polling booth that they regain the conviction they had settled upon before the campaign started.

The proof is to be found in the Two Month Rule (copyright, Spectator Entrails Analysis Ltd). At every general election since the war, the party which has been ahead in the Gallup poll two months before polling day has won the election — and often by much the same margin — except in 1950 when there had been no poll two months before the election.

What would have happened if Mr Callaghan had taken the plunge last October? Well, after standing fairly even in the Gallup ratings through the summer, Labour pulled 4 per cent ahead of the Tories in August, so Mr Callaghan's chances might have been rather better than was suggested by Mr Bob Worcester of MORI, his private pollster. But now the caravan has moved on, the water's under the bridge and Mr Callaghan has taken his leave, dignified and rather sweet, no longer the formidable ogre that used to haunt the dreams of Tory backbenchers but a kindly old gentleman, for the time being.

Previous page

Previous page