PARTY AND ECONOMICAL POLITICS. THE state of parties, arising out

of the new policy of the Tories, is at length so well understood, that we are disposed to drop the subject until some new fact shall occur to alter the complexion of things. Ministers must soon determine their own fate, as well as the course which it will behove the Reformers to pursue. For six months incessantly we have laboured to enlighten the Whigs as to the feelings of the country and the dangerous position in which they are placed by the LYNDHURST tactics. It will pre- sently be seen whether, in the words of Mr. HUTT, they are "equal to this great occasion for the display of statesman-like qualities." But in no event shall we despair of the cause of Re- form. If the Whigs will lead the Reformers, so much the better; but if not, Radicalism, which looks to the removal of "practical evils innumerable,r* can set up for itself. Whether or not assisted by the Whigs, the Tories will not be able to withhold from us much longer the natural and necessary consequences of the Reform Bill. The People are awake, whatever Ministers may be ; and a period of strong political agitation is approaching, from which the triumph of the popular cause may be confidently anticipated. Meanwhile, a new state of economical circumstances will force itself upon the attention of all men ; and for two distinct reasons,— first, because nearly all men must be affected in some of their private interests by a change from prosperity to adversity in re- spect to profits and wages ; and secondly, because of the great influence which economical circumstances have upon party or pure politics. A very clever party politician, Mr. CROKER, opposed the

Reform Bill upon one ground in particular. He asserted, and with perfect truth, that for several years before 1830, there had been no demand for Parliamentary Reform. But either he did not discover, or did not choose to say, that the indifference of the People to the state of the representation was in appearance merely. True it is that Reform of Parliament was seldom named in the petitions of the People for several years previous to the death of GEORGE the Fourth ; but during those years the People did petition most earnestly for the removal of "practical evils innumerable." Those petitions were entirely neglected ; and this gradually produced a general conviction of the necessity of obtaining for the People a real representation in the House of Commons. Still, Reform of Parliament was not demanded. No; because the demand would then have been treated with scorn by the aristocratic order of both parties. Opportunity was wanting. And it should be observed of the masses, that they ap- pear to be guided by a sort of instinct which tells them when to agitate with effect. The opportunity for agitating with effect was given by the death of GEORGE the Fourth and the French Revo- lution of July ; and then, as Mr. CROKER (probably) said in the Quarterly Review, there was a sudden "chaos of unanimity" for Parliamentary Reform. The people seized the first opportunity of demanding with effect the removal of that which a total ne- • Nadu ood's admission.

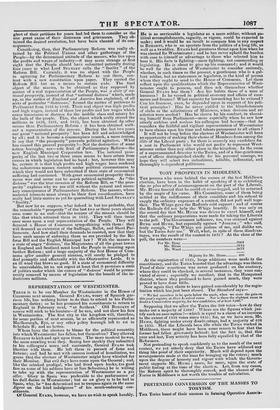

glect of their petitions for years had led them to consider as the one great cause of their distresses and grievances. They ob- tained the desired revolution, but have been cheated of its con- sequences. Considering, then, that Parliamentary Reform was really ob- tained by the Political Unions and other gatherings of the People—by the determined attitude of the masses, who live upon the profits and wages of industry—it may seem strange at first sight that the People should have submitted patiently during

four years to what Lord STANLEY calls the " finality" of the

Reform Bill. Certainly, it was no object with the People in agitating for Parliamentary Reform to rest there, con- tent with a new constitution upon paper. They carried the Reform Bill but as a means to certain ends. The final object of the masses, to be obtained as they supposed by

means of a real representation of the People, was a state of na- tional prosperity, instead of that "national distress" which, made up, as the author of England and America has explained, of all sorts of particular "distresses," formed the matter of petitions to Parliament from 1816 to 1830. Their real object was high profits and high wages, instead of those low profits and low wages which cause uneasiness or distress for the middle class and misery for the bulk of the people. This, the object which really stirred the millions in 1830, 1831, and 1832, has been obtained by other means than Parliamentary Reform : it has been obtained with- out a representation of' the masses. During the last two years our great "national prosperity" has been felt and acknowledged by all ; and it is become a commonplace remark, a mere truism, to say that "the prosperity" prevents political agitation. What has caused this general prosperity ?—Not the destruction of some rotten boroughs, nor—sole fruit of Parliamentary Reform—the new English Municipal Corporation law. The national pres- perity of the last two or three years seems to have arisen from causes in which legislation had no hand ; but, however this may be, certain it is that high profits and high wages have rendered the industrious masses content under political circumstances to which they would not have submitted if their state of economical suffering had continued. With great economical prosperity there never was and never can be much political agitation. As 'the distress "was the true occasion of the Reform Bill, so "the pros- perity" explains why we are still without the natural and neces- sary consequences of Parliamentary Reform. The masses, whose material interests must always be their first consideration, have really had little motive as yet for quarrelling with Lord STANLEY'S "finality." But now let us suppose, what indeed is but too probable, that the remarkable " prosperity " of the last two or three years should soon come to an end—that the temper of the masses should be like that which actuated them in 1832. They will then insist once more upon a real representation of the People. They will demand a House of Commons sympathizing with them : they will demand an extension of the Suffrage, Ballot, and Short Par- liaments. And how shall their demands be resisted, now that they have such means of enforcing them as are provided by the Re- form Bill and the English Municipal law ? With the masses in a state of angry "distress," the Magistrates of all the great towns in England and Scotland must head the People in insisting upon further Reform ; and a large majority of the first House of Com- mons after another general election, will surely be pledged to deal promptly and effectually with the Obstructive Lords. It is an ill wind that blows no good. If a state of economical difficulty be unavoidable, let us not regret at least that it promises a state of politics under which the causes of "distress" would be perma- nently removed by means of legislation for the benefit of the in- dustrious millions.

Previous page

Previous page