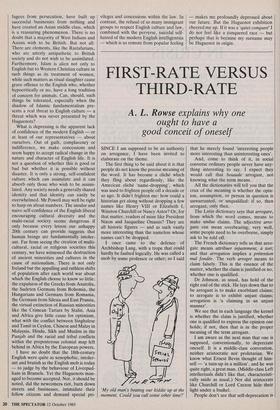

FIRST-RATE VERSUS THIRD-RATE

A. L. Rowse explains why one

ought to have a good conceit of oneself

SINCE I am supposed to be an authority on arrogance, I have been invited to elaborate on the theme.

The first thing to be said about it is that people do not know the precise meaning of the word. It has become a cliché which they fling about regardlessly, like the American cliché `name-dropping', which was used to frighten people off a decade or so ago. It didn't frighten me: how could a historian get along without dropping a few names like Henry VIII or Elizabeth I, Winston Churchill or Nancy Astor? Or, for that matter, readers of mine like President Nixon and Jacqueline Onassis? They are all historic figures — and as such vastly more interesting than the nameless whose names can't be dropped.

I once came to the defence of Archbishop Lang, with a trope that could hardly be faulted logically. He was called a snob by some professor or other; so I said 'My old man's beating our kiddie up at the moment. Could you call some other time?' that he merely found 'interesting people more interesting than uninteresting ones'.

And, come to think of it, in social converse ordinary people never have any- thing interesting to say. I expect they would call that boutade arrogant, not knowing what the term means.

All the dictionaries will tell you that the crux of the meaning is whether the opin- ion, assumption, or person in question is unwarranted, or unqualified: if so, then arrogant, only then.

The Latin dictionary says that arrogare, from which the word comes, means to make undue claims. The adjective arro- gans can mean overbearing; very well, some people need to be overborne, simply ask to be told off.

The French dictionary tells us that arro- gate means attribuer injustement, a tort; and that arrogation implies a pretention mal fondee. The verb arroger means to claim falsely. This is the essence of the matter, whether the claim is justified or no, whether one is qualified.

Dr Johnson, as usual, has hold of the right end of the stick. He lays down that to be arrogant is to make exorbitant claims; to arrogate is to exhibit unjust claims; arrogation is 'a claiming in an unjust manner'.

We see that in each language the kernel is whether the claim is justified, whether one is qualified to express the opinion one holds; if not, then that is in the proper meaning of the term arrogant.

I am aware as the next man that one is supposed, conventionally, to depreciate oneself. It is a middle-class convention, neither aristocratic nor proletarian. We know what Ernest Bevin thought of him- self — 'a turn-up in a million', and he was quite right, a great man. (Middle-class Left intellectuals didn't like that, characteristi- cally snide as usual.) Nor did aristocrats like Churchill or Lord Curzon hide their light under a bushel.

People don't see that self-deprecation is a ploy to recommend oneself; French moralists like La Rochefoucauld and Chamfort realised that perfectly well. Cyril Connolly made a literary career out of running himself down. It appeals to other people's self-esteem, who were fools enough to be taken in by it — I never was. Even dear John Betjeman had a way of calling himself an ant, a 'mere emmet', etc: it was partly genuine in his case, partly a way of sucking up to the public, an element in this far-from-demotic figure really be- coming a cultural idol, a mascot of the large-hearted people. I find this convention of depreciating oneself too obvious, and a bore: I think it beneath me. It strikes me as ludicrous when the great historian Froude finds it proper to be 'extremely humble' when addressing a lot of county antiquarians. It is simply portentous when George Eliot refers to her 'little personal share of life in the world' as 'mere standing room'.

Note that both these were middle-class Victorians. The historian knows that the habit of understatement, the humour of under-emphasis, is rather late-Victorian and essentially bourgeois. It is certainly not Elizabethan or Georgian — think of Hogarth; or Regency — think of Rowland- son; nor is it lower-class — think of Dickens. Historically, English humour has been that of over-emphasis, exaggeration rather than under-emphasis.

So — under-emphasis, self-depreciation etc are apt to be colourless, reducing everything to grey monochrome. It is modern English, middle-class, and very public school. Since I am none of these things, I do not subscribe to it; as a historian I know how limited, and restric- tive, the convention is, and never allow myself to be controlled by it. Fancy think- ing that such people have any authority!

Yet, when my first personal book, A Cornish Childhood, came out Raymond Mortimer, after a paean of praise, in- structed the young author that one ought not to betray a good opinion of oneself. One ought to write oneself down, so that when people give themselves away by mistake, one may then have the laugh on them. Can't one see the silly sissies, like Raymond, having a nice little giggle?

Young as I then was, I saw no reason why he should lay down the law for me. Nor have I ever allowed myself to be frightened off by inferior people thinking to set the standards — I know how historically short-lived they are. Dr John- son would not have allowed himself to be put off by them. In fact, psychologically, it is good for people to have a good conceit of them- selves. I have known several people of real gifts who have never fulfilled them simply for want of confidence in themselves. They should be encouraged to have a good opinion of themselves, not be discouraged by the instinctive way the inferior have of frustrating, sapping, undermining, if they can.

Myself, I never pay the slightest atten-

tion to what the third-rate think throughout human history it has always been mostly nonsense. The only thing that is of interest is its sociological aspect. A third-rate society naturally has third-rate standards (if that is the word for it). Throwing around the word elitist as if it were pejorative is an obvious ploy to elide the difference between the first-rate and themselves.

A well-known authority on literacy, in an illiterate society, told me that on the Arts Council people couldn't bear to think that any writer was better than themselves. That shows the absence of standards, besides being a great bore. Throwing around the word 'arrogant', without any idea of its proper meaning, has the same sociological significance: they hate the first-rate and want to bring it down to their own level of insignificance.

Had William Shakespeare a good con- ceit of himself?

No one in the whole wide world of Shakespearean writing had ever spotted the autobiographical nature of The Two Gentlemen of Verona, until I got to work on it. That is the reason why it had no known source: the two friends competing for the love of the same woman were evidently Shakespeare and the young Pat- ron in rivalry for Emilia Lanier. Shakespeare recognisably describes the young man turned to folly, losing his promise, etc, while love turns the head of `the finest wits of all'. That is what William

Shakespeare thought of himself — justifi- ably, even quite early on, 1592, for I was able to settle the date along with the relevant Sonnets.

All these findings and discoveries by the leading authority on the age are quite unanswerable and definitive. The third- rate of the Shakespeare industry canot bear to think that they were not made by themselves.

A kindly American professor said, 'I think that if you had come to the Eng. Lit. people, with your cap in your hand, and said "I submit all this to your better judgment", they would be better pleased.' Rather taken aback, I said: 'But I can't say that: these are the answers, and they are right.' He replied, 'I know — but think what they would have done to you, if you had been wrong!'

Professor Ricks wrote that, if I hadn't been so aggressive, they would have fol- lowed me 'like lambs'. But how could one not be aggressive, when faced by such obtuseness and obstruction? They can't answer any of it, and they never will.

`Arrogant'? The simple test is that given by the authorities at the outset, i.e. whether the claim is justified or not. One does not respect the reaction of the third- rate as to that — it is they who do not qualify. After a lifetime spent in Eliza- bethan research, the necessary qualifica- tion for knowing about Shakespeare, I should not be worth my keep if I were not qualified — as they are not.

Previous page

Previous page