ARTS

Theatre

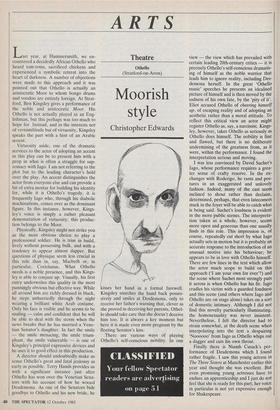

Othello

(Stratford-on-Avon)

Moorish style

Christopher Edwards

Last year, at Hammersmith, we en- countered a decidedly African Othello who heard tom-toms, sacrificed chickens and experienced a symbolic retreat into the heart of darkness, A number of objections were made to this approach and it was pointed out that Othello is actually an aristocratic Moor to whom bongo drums and voodoo are entirely foreign. At Strat- ford, Ben Kingsley gives a performance of the noble and aristocratic Moor. His Othello is not actually played as an Eng- lishman, but this perhaps was too much to hope for. Instead, and in the interests not' of verisimilitude but of virtuosity, Kingsley speaks the part with a hint of an Arabic accent.

Virtuosity aside, one of the dramatic services to the actor of adopting an accent in this play can be to present him with a prop in what is often a struggle for sup- remacy with Iago. I am not referring to the plot but to the leading character's hold over the play. An accent distinguishes the actor from everyone else and can provide a bit of extra mortar for building his identity for, while it is Othello's tragedy, it is frequently Iago who, through his diabolic machinations, comes over as the dominant figure. In this instance, however, Kings- ley's voice is simply a rather pleasant demonstration of virtuosity; this produc- tion belongs to the Moor.

Physically, Kingsley might not strike you as the most obvious choice to play a professional soldier. He is trim in build, lively without possessing bulk, and with a tendency to appear almost dapper. But questions of physique seem less crucial in this role than in, say, Macbeth or, in particular, Coriolanus. What Othello needs is a noble presence, and this Kings- ley is able to conjure up. Visually, his first entry underwrites this quality in the most punningly obvious but effective way. While all around him are richly dressed in black, he steps unhurriedly through the night wearing a brilliant white Arab costume. Only his face is visible and he seems to be smiling — calm and confident that he will be able to deal with the storm when the news breaks that he has married a Vene- tian Senator's daughter. In fact the smile — the smile menacing, the smile trium- phant, the smile vulnerable — is one of Kingsley's principal expressive devices and he uses it to good effect in this production.

A director should undoubtedly make us sense Othello's great and fatal jealousy as early as possible. Terry Hands provides us with a significant instance just after Othello has won over the Venetian Sena- tors with his account of how he wooed Desdemona. As one of the Senators bids goodbye to Othello and his new bride, he kisses her hand in a formal farewell. Kingsley snatches the hand back posses- sively and smiles at Desdemona, only to receive her father's warning that, clever as she proved in deceiving her parents, Othel- lo should take care that she doesn't deceive him too. It is always a key moment but here it is made even more pregnant by the fleeting Senator's kiss.

There are various ways of playing Othello's self-conscious nobility. In one view — the view which has prevailed with certain leading 20th-century critics — it is. precisely Othello's self-conscious dramatis- ing of himself as the noble warrior that leads him to ignore reality, including Des- demona herself. In the great 'Othello music' speeches he presents an idealised picture of himself and is then moved by the sadness of his own fate, by the 'pity of it'. Eliot accused Othello of cheering himself up, of escaping reality and of adopting an aesthetic rather than a moral attitude. To reflect this critical view an actor might register Othello as, say, a narcissist. Kings- ley, however, takes Othello as seriously as Othello does himself. The nobility is fine and flawed, but there is no deliberate undermining of the greatness from, as it were, within the performance. I found the interpretation serious and moving.

I was less convinced by David Suchet's Iago, whose performance requires a grea- ter sense of crafty reserve. In the ex- changes with Roderigo, he rants and pos- tures in an exaggerated and unlovely fashion. Indeed, many of the cast seem inclined to shout rather than declaim, determined, perhaps, that even latecomers stuck in the foyer will be able to catch what is being said. Suchet's loudness is evident in the more public scenes. The interpreta- tion taken as a whole, however, seems more open and generous than one usually finds in this role. This impression is, of course, repeatedly cut short by what Iago actually sets in motion but it is probably an accurate response to the introduction of an unusual motive into his behaviour; he appears to be in love with Othello himself. There are few lines in the text which allow the actor much scope to build on this approach CI am your own for ever'?) and the scene where Suchet most strongly puts it across is when Othello has his fit. Iago cradles his victim with a guarded fondness and this scene (and others where Iago and Othello are on stage alone) takes on a sort of domestic intimacy. Although I did not find this novelty particularly illuminating, the homosexuality was never insistent. Nevertheless, I felt the director had to strain somewhat, at the death scene when interpolating into the text a despairing `N000000' from Iago as Othello whips out a dagger and cuts his own throat.

Finally there is Niamh Cusack's per- formance of Desdemona which I found rather fragile. I saw this young actress in The Three Sisters at Manchester earlier this year and thought she was excellent. But even promising young actresses have to endure an apprenticeship and I just do not feel that she is ready for this part; her voice in particular is not yet expressive enough for Shakespeare.

Previous page

Previous page