Architecture

Art and Craft: Architectural Drawings of the Regency Period (RIBA Heinz Gallery, till 26 October)

Reassessing the Regency

Alan Powers

thought to learn great things: I found I had to act small ones. I had dreamed of columnar splendours, arcaded magnifi- cence, of firmamental domes, of "heaven- dictated spires": I found economic contrivance and a parsimonious minimum Of decoration, for cupolas, plain flat ceil- ings; for steeples nothing more elevated than chimney tops.' So wrote George Wightwick of his pupillage with Edward Lapidge in 1818. The architecture of the Regency encompasses both these extremes, and this exhibition, with an accompanying book, Architectural Drawings of the Regency Period, by the selector Giles Worsley (Andre Deutsch, £25 hardback, £14.99 Paperback), the first in a new series, avoids the temptation to pick only the plums from the British Architectural Library's drawings collection.

The concentration is not on drawings that were made to create an impression on Competition committees or Royal Academy crowds (although these are well represent- ed), but on those that indicate the develop- ment of the architectural profession. During this period, architects became more distinctly separated from surveyors, joiners and other trades to which they had previ- ously enjoyed a close relationship. By 1837, their institute had acquired its royal char- ter, although it took another hundred years to restrict the title of 'architect' to those who had achieved the official qualifications for registration. The drawings help to show the evolution from the architect's notes to himself, to the drawing intended to impress the client, and lastly to the contract draw- ing treated as a legal document. Although larger than most earlier drawings, those of the Regency remain of manageable size, and are often of exquisite workmanship themselves.

Mundane but necessary buildings are Included, such as William Burn's Crighton Royal Institution, a lunatic asylum in Dum- fries by the future master of Scottish Baro- nial, in which drawings allow for an intimate study of the water-closet and fire- guard. John Buonarotti Papworth, a dili- gent and accomplished if unoriginal architect, left a comprehensive archive of drawings which allow one into the working of the butler's pantry in a grand suburban villa, with a draining rack for 18 decanters. Papworth's drawings for shop fronts indi- cate the highly tuned elegance required by fashionable businesses, the equivalent of Eva Jiricna's shop interiors in Sloane Street.

Not everything was on this level of veneer and polished surface. C.R. Cock- erell was beginning his lonely quest for a modern classicism that was at once roman- tic and scholarly, in contrast to the bald- ness of the Greek Revival. The valediction to the extended Regency (1790-1837) is A. W. N. Pugin's watercolour of his house, St Marie's Grange, Salisbury, seen against the sunset, which stands out as a different way of seeing buildings and portraying them as architectural mass rather than planes and details, presaging the Victori- ans' overturning of the rule of taste.

The title Art and Craft refers to the craftsmanship of the drawings themselves but it is ironic that during this period every effort was made to exclude from architec- ture the evidence of human handwork which also merits the name of craft. After the Gothic Revival, Queen Anne and Arts and Crafts movements, English architects felt a strong pull back towards the smooth accomplishment of the Regency, and expressed it in numerous books and build- ings from the late Edwardian period through to the 1950s. This enthusiasm was transmuted by, among others, Giles Wors- ley's predecessor as architectural editor of Country Life, Christopher Hussey, into a genealogy for English modernism in the 1930s which presumed that if the threads of Sir John Soane's work could be taken up, the intervening years would vanish like a bad dream. I cannot therefore agree with Giles Worsley's assertion that 'Regency architecture has never been very fashion-

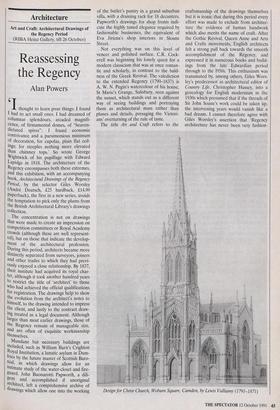

Design for Christ Church, Woburn Square, Camden, by Lewis Vulliamy (1791-1871) able', but he has provided a visually and intellectually stimulating reassessment of the period.

Previous page

Previous page