Notebook

I n one of the last articles which he wrote from Egypt for the Spectator before his death earlier this year, Desmond Stewart quoted approvingly from a biography of Nasser: 'The monstrous structure he controlled — the Egyptian State — tends to transform any well-intentioned ruler into a tyrant, unless he is prepared to limit its and his own powers.' President Sadat, of course, has had no wish to limit either, with the predictable consequences. The repressive measures of the past few days have only provided further evidence of his tyranny. But they were spectacular nevertheless. 'President sacks Pope' is a stirring headline with Napoleonic overtones. When I read it, I wondered if President Sadat might not have been influenced by Mr C. H. Sisson's recent series of articles in the Spectator about the proper relationship between Church and State. But whatever may have persuaded Mr Sadat to boot out the Coptic Patriarch, it is strange how nobody seems to mind about it. Imagine the fuss there would be if a Cardinal were similarly treated by a secular ruler. According to Wednesday's Times, there is more outrage at the detention of the journalist Mohammed Heikal. Do the Copts have no friends? I must say that on the one occasion when I attended a Coptic service in Cairo, I was not very favourably impressed. It was all mess and muddle and Arabic wailing. It was, I imagine, a Christian service, but it was difficult for a westerner to recognise it as such. However, the Coptic Church has an ancient tradition. Its Patriarch has been received by the Pope in Rome. It is curious that nobody is standing up for him.

For once, lzvestia seems to have got it right. There was indeed `no proof or evidence' for the theory, aired in a television documentary and in the Guardian, that the KGB was behind the assassination attempt on Pope John-Paul II. The paper was properly outraged that a horrid little Turkish hit-man — 'this riff-raff', as hvestia called him — should have been mistaken by anybody for a Communist agent. Communist agents, one is led to assume, are recruited from a better class of person. Despite the Guardian's extraordinary claim that `thc Vatican intelligence sources are among the best in the world', the Vatican also denies having ever suggested there was an international plot to kill the Pope. Being presumably short of intelligence agents in Turkey or Bulgaria, it probably knows very little more than the rest of us. Still, the temptation to construct a plausible conspiracy theory around the attempt is understandable, even if — in the absence of any evidence whatsoever — it is surprising of the television and the Guardian to make such a meal of it. The fact is, however, that the KGB theory is not the only plausible one available. The Spectator's team of experts — i.e. Peter Hebblethwaite — finds one major flaw in it. It reduces the assassin, Mehemet Ali Agca, to an unheeding instrument of the KGB, ignoring the significance of his Moslem background. When, for example, Ali first threatened to kill the Pope in November 1979, he referred to him as 'that Christian crusader' — not the sort of description one would expect from an agent of the KGB. Altogether more plausible, if equally unproven and unprovable, is the theory that Ali was acting on behalf of the Libyans. Under interrogation, Ali became nervous at any mention of Libya and denied indignantly that he had ever been there. Even if he was telling the truth, he had come close enough to arouse suspicion. He admitted to having been in Tunisia, which has a common frontier with Libya, and of having been commissioned there to murder Dom Mintoff and President Bourguiba; commissions he declined because, he said, 'they did not fit in with my ideals.' So he had ideals, some reason for trying to kill the Pope and some reason for not killing Bourguiba or Mintoff. He was not an undiscriminating 'gun for hire'. Following his trip to Tunisia, he made another mysterious journey last April to Palma, Majorca, only a few days before he shot the Pope in St Peter's Square. Might he not, once again, have been making contact with his backers? To support this theory is the fact that Ali, as a secularised Moslem, would be more likely to turn tó Libya than to the Communists. He also shared with Gaddafi a misunderstanding of the nature of the Vatican City State, both of them having on different occasions referred to it as if it were a conventional state governed, as in Moslem countries, according to the principles of the holy book. If, indeed, Ali was acting on behalf of Gaddafi, the motive is clear enough. He would have been contributing to the 'destabilisation' of the West, which is the object of Libyan policy. None of this may be true, but it is at least as good a theory as the other.

I t is particularly satisfying to find oneself paraded on the Guardian's Woman's page as an example of a male chauvinist pig for a remark which was obviously intendea as a joke, it being the assumption behind all attacks on Guardian-reading feminists that they have no sense of humour. I was afforded this satisfaction last Monday for a comment upon the high cost of buying female slaves in India. Although they have for some time been the laughing stock of the country, these extraordinary Guardian women are more and more in evidence. They are even, according to our reporter in Blackpool, to be found in ever increasing numbers among trade unionists. Typical of them is the lady from the local government union NALGO, who complained at the TUC congress on Wednesday that there were still men in the movement who did not recognise that 'hot flushes during the menopause are a trade union issue.' In contrast, there are still very few black trade unionists to be seen. Against the dreariness of the proceedings, Michael Foot's speech on Tuesday must have been thrilling. But even he managed to leave the union men feeling restless and unhappy. His defence of Labour government experiments in incomes policy was, as far as his audience was concerned, a serious gaffe. Free collective bargaining now rules, even though its union, devotees do not appear to have realised that dependence on the free market mechanism can lower their members' living standards just as effectively as any incomes policy. None of Mr Foot's Old Testament oratory made much impact after he had committed this great heresy. Our reporter suggested to the leader of one Civil Service union that it had been a fine Burkean oration. 'My young delegates,' he replied (with the new brutalism much more common among the white collar trade unionists than among the miners and dockers), 'thought he made a right berk of himself.' Mr Foot's oratory is at least preferable to that of Mr Benn, who, particularly since his illness, sounds like a robot — monotonous and relentlessly unpausing. He sounds as if he was reading from a television autocue.

I f it is not too late, which it probably is, I would urge Mrs Thatcher not to dismiss Sir Ian Gilmour in her imminent cabinet reshuffle. I can well see why she might feel tempted to do so. He is not perhaps the most committed of ministers. He is certainly not among the most loyal of her supporters. He even spends summer holidays in Italy with Mr Roy Jenkins. But apart from the fact that, as a former editor of the Spectator, he deserves special consideration, it would be rash of her to exclude him from her government. Being a much less sentimental man than Mr Norman St John Stevas, he would not hesitate to stir up opposition to the Prime Minister and he would present a more attractive rallying point for other Tory wets'. Perhaps his friend Mr Jenkins might even persuade him to join the SDP.

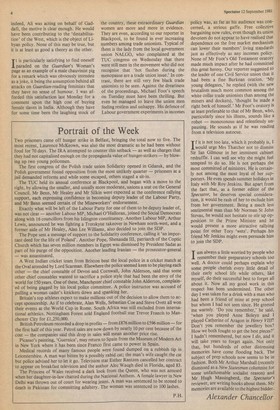

T am always a little worried by people who 1 remember their preparatory schools too well. A doctor could perhaps explain why some people cherish every little detail of their early school life while others, like myself, do their successful best to forget all about it. Now all my good work in this respect has been undermined. The other day I was taken for a drink with a man who had been a friend of mine at prep school but whom I had not seen since. He greeted me warmly. 'Do you remember,' he said, 'when you played Anne Boleyn and I played Catherine of Aragon in Henry VIII? Don't you remember the jewellery box? How we both fought to get the best pieces?' I hadn't remembered, but now I do, and it will take years to forget again. Not only that, but hundreds of other distressing memories have come flooding back. The subject of prep schools now seems to be in fashion. Both Mr Arthur Marshall (recently dismissed as a New Statesman columnist for some unfathomable socialist reason) and Mr Hugh Massingberd, the Spectator's reviewer, are writing books about them. My memories are available to the highest bidder.

Alexander Chancellor

Previous page

Previous page