Art

Waking up in Washington

Giles Auty

Wliether or not travel broadens the mind, it can certainly help focus it. Why it took a recent stay in Washington to make me wake up to something which should have been clear to me all along, I cannot say.

To be fair, a suspicion of what I have later realised had been lurking in my mind since last January, when I attended the Opening of the giant survey American Art 1930-70 at Lingotto, the converted former Fiat factory in Turin. Four decades of American art were represented there by some 200 works from over 120 artists. From certain vantage points whole decades of American art could be taken in at a glance. This last is not just a most unusual facility, allowed by the singular proportions of Lingotto, but one which can prompt important insights. The message that came to me personally was: Is this all American art really amounted to over such a long peri- od? Acres of abstract expressionist, colour- field, hard-edge, Pop and minimal works seemed suddenly like a visual desert, lack- ing largely in human resonance or cultural Profundity. I grew up in an era of apparent American domination of contemporary visual culture. Could it be that our supine acceptance of this hegemony has been an error of considerable proportions and sig- nificance?

It would take an intrepid critic to assert that the art of an entire nation has been Consistently overvalued. No doubt many, in America especially, would be quick to ridicule such a view. In any case, the issue

would be hard to prove one way or the other. What I prefer to suggest is that an understandable American anxiety to claim international significance for their art obliged them to adopt art-historical argu- ments of a particularly tendentious nature. Until I was in Washington recently I had been inclined to forget that the hoary mod- ernist version of artistic evolution might still enjoy widespread credence anywhere. But a walk round Washington's museums and a glance at the catalogues they offered quickly demonstrated to me that this sim- plistic and misguided reading of art history is still very far from dead — in the capital of the United States, at least.

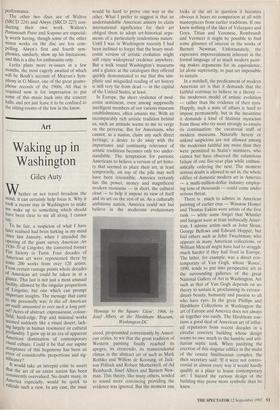

In Europe, the sheer virulence of mod- ernist sentiment, even among supposedly intelligent members of our various museum establishments, often amazes me. With an incomparably rich artistic tradition behind us, such an attitude seems to me to verge on the perverse. But for Americans, who cannot, as a nation, claim any such direct heritage, a desire to do away with the importance and continuing relevance of artistic traditions becomes only too under- standable. The temptation for patriotic Americans to believe a version of art histo- ry that seemed to place their art, at least temporarily, on top of the pile may well have been irresistible. America certainly has the power, money and magnificent modern museums — in short, the cultural clout — to help it impose its view of itself and its art on the rest of us. As a culturally ambitious nation, America could not but believe in the modernist evolutionary 'Homage to the Square: Glow', 1966, by Josef Albers, at the Hirshhom Museum, Washington DC creed, propounded conveniently by Ameri- can critics, to wit that the great tradition of Western painting finally reached its apogee, its crescendo, its transcendental climax in the abstract art of such as Mark Rothko and Willem de Kooning, of Jack- son Pollock and Robert Motherwell, of Ad Reinhardt, Josef Albers and Barnett New- man. This theory, like many others, tended to sound more convincing providing the evidence was ignored. But the moment one looks at the art in question it becomes obvious it bears no comparison at all with masterpieces from earlier traditions. If one knew nothing of the likes of Velazquez and Goya, Titian and Veronese, Rembrandt and Vermeer it might be possible to find some glimmer of interest in the works of Barnett Newman. Unfortunately, the expressive impoverishment inherent in the formal language of so much modern paint- ing makes arguments for its equivalence, let alone superiority, to past art impossible to sustain.

In a nutshell, the predicament of modern American art is that it demands that the faithful continue to believe in a theory — the modernist model of artistic evolution — rather than the evidence of their eyes. Happily, such a state of affairs is hard to impose permanently, but in the meantime it demands a kind of Stalinist mysticism from those who try most strongly to ensure its continuation: the curatorial staff of modern museums. Naturally heresy or unkind suspicions are not allowed among the modernist faithful any more than they were permitted to Stalin's ministers, who cannot but have observed the calamitous failure of one five-year plan while enthusi- astically ordering the next. The moment serious doubt is allowed to set in, the whole edifice of domestic modern art in America — a multi-million-dollar industry employ- ing tens of thousands — could come under serious threat.

There is much to admire in American painting of earlier eras — Winslow Homer and Thomas Eakins were artists of the first rank -- while some forget that Whistler and Sargent were at least technically Amer- ican. I admire artists such as John Sloan, George Bellows and Edward Hopper, but feel others such as John Twachtman, who appears in many American collections, or William Metcalf might have had to struggle much harder if they had lived in Europe. The latter, for example, was a direct con- temporary of Van Gogh, whose 'Roses', 1890, tends to put into perspective art in the surrounding galleries of the great National Gallery of Art in Washington. Art such as that of Van Gogh depends on no theory to sustain it, proclaiming its extraor- dinary beauty, humanity and passion to all who have eyes. In the great Phillips and Hirshhorn Collections in Washington the art of Europe and America does not always sit together too easily. The Hirshhorn con- tains a good deal of American art of inflat- ed reputation from recent decades in a circular concrete building whose design seems to owe much to the humble and util- itarian septic tank. When justifying the erection of this singular edifice in the midst of the ornate Smithsonian complex, the then secretary said: 'If it were not contro- versial in almost every way it would hardly qualify as a place to house contemporary art.' I hazard the curious design of the building may prove more symbolic than he knew.

Previous page

Previous page