JAM VINDICATED

A report this week from Islington Council's chief executive demonstrates the truth of my 1995 article, writes Leo McKinstry THE LONDON Borough of Islington, long a byword for municipal incompe- tence, has grown used to hostile criticism, but few attacks on its management have been more brutal than the one which has emerged this week. In a verbal assault, Labour-run Islington is described as 'self- serving, disempowered and bureaucratic', riddled with staff who 'neither know nor care that the services they provide are well below the standard the public has a right to expect'. The council is 'badly lacking in corporate leadership', has a 'dysfunctional neighbourhood office system' and a 'histo- ry of shocking failures in providing services to the most vulnerable'.

Who is the author of this philippic? Not some Tory Central Office spin doctor, nor an opposition councillor, nor a disgruntled ex-employee. It is Islington's own £90,000- a-year chief executive, Leisha Fullick. Ms Fullick, who took over the top job in the council only two years ago, is appalled at what she has found in the organisation. In her report, 'Modernising Islington', which is to be debated by elected council mem- bers next month, she depicts a world of buck-passing, cynicism and ineptitude. 'The term customer may have got into our vocabulary but it certainly isn't informing our collective thinking,' she writes.

As a former Islington Labour councillor, I recognise all too clearly Ms Fullick's scathing analysis. Indeed, in January 1995, almost a year after I lost my seat on the council, I wrote an article in The Spectator making very similar criticisms of the bor- ough. In that piece, I referred to the 'cock- tail of political correctness, bureaucracy and abuse of public money' which charac- terises its work. Attacking the gross ineffi- ciencies of the workforce and manage- ment, I exploded the myth that the coun- cil's problems were due to `underfunding', the excuse so often used by officials to explain away their every failing.

The article created something of a storm, featuring in both Prime Minister's Questions and Tory party political broad- casts. From the Labour side, my words were dismissed as the bitter rantings of a failed politician. It was said by Labour press officers that I wanted my 'five min- utes of fame', while Islington council claimed that I, motivated by spite, had wil- fully ignored the great improvements the borough had made in the Nineties.

But now, according to the chief execu- tive, I was right. And Ms Fullick says in her report that the kind of response made to my Spectator article was all too typical of council attitudes. For too long, she says, the Town Hall has refused to acknowledge its mistakes. 'We have wasted precious years being defensive about the indefensible.'

Defensiveness is certainly not one of the chief executive's faults. Rather, she lays into her own organisation with a gusto . which would make Gerald Ratner blush. No department is spared her invective. The borough's housing section, for example, has some of 'the worst performance indicators in the country'. Islington schools are 'held in low esteem by parents' and are constant- ly vilified in the press'. A record of 'poor financial decision-making and manage- ment' has led to 'high levels of debt, no financial stability and constant public criti- cism'. Overall, the council 'lacks vision', is 'predominantly provider-driven' and is 'vul- nerable to lobbying groups'. Attempts at change have failed because staff feel that 'if you ignore them for long enough they will simply go away to be replaced by the next management fad. The old, dysfunctional systems, processes and cultures survive them all.'

There is a wealth of recent evidence to back up Ms Fullick's claims. Islington's schools, far from improving, are becoming worse. GCSE results showed that this year only 23.4 per cent of pupils gained five or more passes graded A to C, a fall of 2 per cent compared to 1997. The national aver- age is 45 per cent, putting Islington amongst the most dismal local education authorities in the country. As usual, one headmaster tried to explain away these atrocious results by claiming they were linked to poverty. If that were true, then why does neighbouring Camden, a bor- ough with much the same demographics as Islington, score 47.8 per cent on GCSE passes?

The continuing dominance of political correctness is reflected in Islington's policy of refusing to co-operate with the Home Office or immigration officials in tackling benefit fraud, a stance which the borough's fraud manager argues is preventing proper investigations and is costing local taxpayers a fortune. Most seriously of all, the dis- graceful arrogance of some employees towards the public has been revealed in two recent tragic cases.

In one, Edith Rockman, a pensioner in her eighties, was left to die in her burning flat when staff on the council's so-called 'Emergency Helpline' ignored her desper- ate pleas for help. In a similar incident, Charlie Gulmini, 85, died after `helpline' staff took 18 hours to go into his flat after he raised the alarm having suffered a stroke. An inquiry into the helpline's actions found 'circumstances which are beyond belief.

But such grim failures are all too believ- able for anyone who has had any acquain- tance with Islington. This is the 'caring' borough which allowed children in its care to be systematically abused by paedophiles on the payroll, and then refused to act against them because of fears of accusa- tions of 'homophobia'. This is the 'model' borough which has squandered tens of mil- lions on hopelessly flawed schemes for decentralisation, on politically correct ini- tiatives like the monumentally useless Women's Equality Unit, and on manage- ment structures designed to produce necrosis and irresponsibility. This is the borough more concerned about deals with the European Union than the collection of rent.

As Ms Fullick rightly says, this disas- trous state of affairs cannot continue. She is therefore proposing radical changes in the way the council operates. What is so fascinating is that her measures are pre- cisely those which municipal Labour has resisted for decades: privatisation, com- mercialisation, cutbacks in council-run ser- vices, and much leaner management. In crucial areas like housing and social work, she proposes 'a drastic reduction in the scale of in-house services and the number of people who work directly for the departments'. In every service, from libraries to planning, she argues for pri- vate-sector involvement, market testing and a tighter focus. Building services, for instance, are to see a 40 per cent fall in the workforce. In this programme of change, nothing is to be sacrosanct, not even the once cherished equal opportunities and race relations policies.

The council, she urges, should shift from being a direct 'provider' of services to being an 'enabler'. This is exactly the sort of language that was sneered at by Labour councillors when it was used by Tories like Nicholas Ridley in the past. But Labour's vision of the local authority as the all-pow- erful employer and provider can be seen to have hopelessly failed, sunk by its own moral and financial bankruptcy. The pro- gramme outlined by Ms Fullick is in line with the approach adopted almost two decades ago by those Tory London flag- ships, Westminster and Wandsworth. It is a delicious irony that Labour councillors may now be compelled to preside over the introduction of the very policies against which they railed so violently in the Eight- ies.

And here lies the great flaw in Ms Ful- lick's paper. She is asking the Labour rulers of Islington to defy all their instincts, to ditch everything they have believed in since they were first elected in 1982. Many of the borough's most senior councillors, like the leader Derek Sawyer and the chair of personnel Sandy Marks, have held top positions for those 16 years during which the current shambles was created. As the highly respected Liberal Democrat Margot Dunn told me, 'The people in power now are those who got us into this mess. Why would they change their spots now? They simply don't have the courage or the vision to take up this approach. All they want to do is demand more money.'

I am as guilty as anyone of failing to change Islington. During my years as chair of personnel until losing my seat in 1994, I became obsessed with trying to cut bureau- cracy and to boost productivity. But I suc- ceeded in neither objective. Making even the smallest improvement in the running of the organisation was like trying to push jelly up a hill. Resistance flared up at every quarter. I vividly recall one meeting with the trade unions when I was trying to make the case for a more customer-orient- ed approach. 'If you mention "changing the culture", I'll throw that glass at you,' said the leading trade union official as he eyed a tumbler sitting in the middle of the table.

This is the sort of mentality Leisha Ful- lick will be up against. She may have an easier task, given that Islington has now sunk so deep in the mire that the only way is up, but I wouldn't count on it. "Things can only get better' was Labour's slogan at the last election. For many Islington resi- dents, it sounds as empty as the borough's coffers.

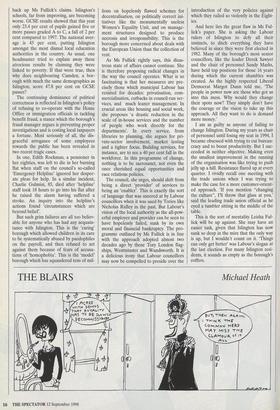

Previous page

Previous page