Design

Raymond Loewy: Pioneer of American Industrial Design (Design Museum, till 19 May)

Styling America

John Henshall

Raymond Loewy was a gifted French designer who arrived in America in 1919, at the age of 26, sure of one thing: single- handedly, he would transform that coun- try's industrial design, and nothing would stand in his way. Self-confident to the point of megalomania, he was to work for 400 leading companies, open offices in New York, Paris and London, and start design's first market research department along the way. His name became synonymous with the artefacts which have become icons of brash, monied, post-second world war America. His clients included Coca-Cola, Greyhound buses, airlines, railways and oil companies — he designed the familiar logos for BP, Shell and Exxon.

Loewy's theories on design were beguil- ingly simple, as this exhibition of some 300 items shows. An unapologetic hedonist, ripe for the glitzy swings of taste and style which swept America with almost pre- dictable regularity, Loewy operated on the principle of 'beauty through function and simplification' and stated that 'between products equal in price, function and quali- ty, the better-looking will outsell the other'. Later he added: 'Industrial design keeps the customer happy, his client in the black, and the designer busy'.

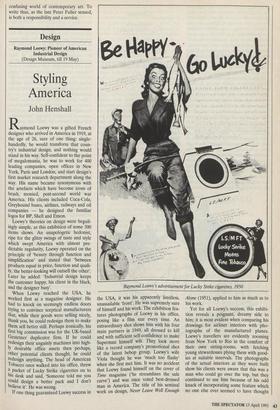

When Loewy reached the USA, he worked first as a magazine designer. He had to knock on seemingly endless doors trying to convince sceptical manufacturers that, while their goods were selling nicely, thank you, he could redesign them to make them sell better still. Perhaps ironically, his first big commission was for the UK-based Gestetner duplicator firm. If he could redesign their ungainly machines into high- lY desirable office assets then perhaps, other potential clients thought, he could redesign anything. The head of American Tobacco once walked into his office, threw a packet of Lucky Strike cigarettes on to his desk and said, 'Someone told me you could design a better pack and I don't believe it'. He was wrong. If one thing guaranteed Loewy success in Raymond Loewy's advertisement for Lucky Strike cigarettes, 1950 the USA, it was his apparently limitless, unassailable 'front'. He was supremely sure of himself and his work. The exhibition fea- tures photographs of Loewy in his office, posing like a film star every time. An extraordinary shot shows him with his four main partners in 1949, all dressed to kill and with sufficient self-confidence to make Superman himself wilt. They look more like a record company's promotional shot of the latest bebop group. Loewy's wife Viola thought he was 'much too flashy' when she first met him. It was no accident that Loewy found himself on the cover of Time magazine (`he streamlines the sale curve') and was once voted best-dressed man in America. The title of his seminal work on design, Never Leave Well Enough Alone (1951), applied to him as much as to his work.

Yet for all Loewy's success, this exhibi- tion reveals a poignant, dreamy side to him; it is most evident when comparing his drawings for airliner interiors with pho- tographs of the manufactured planes. Loewy's travellers are evidently zooming from New York to Rio in the comfort of their own sitting-rooms, with fetching young stewardesses plying them with good- ies at suitable intervals. The photographs of the actual interiors as they were built show his clients were aware that this was a man who could go over the top, but they continued to use him because of his odd knack of incorporating some feature which no one else ever seemed to have thought of. His work for the NASA space agency in the late 1960s exemplifies this: one thing the agency had apparently not included in the brief was a window. Loewy, ever the practical visionary, immediately realised the astronauts might like to see space whizzing by as they travelled through it. However, his overall concepts for the mod- ules were not used — which was hardly sur- prising, since to look at his mock-ups, if Ground Control had called these Major Toms, they'd have interrupted them swig- ging whisky and playing poker.

Angela Schonberger, of the International Design Centre in Berlin, curated the show and edited its excellent, large-format cata- logue (Prestel, f16.95). She told me: `Advertising and design have become the art form of the century; we are defined by them. For my generation, growing up in Germany after the war, Americana was everywhere. It was a shock to discover how much work went into these apparently effortless items. It was a bigger one to learn how many of them were the work of one man — Raymond Loewy.' She might have added that Loewy's output is the more remarkable because much of the material we associate automatically with successful, consumerist, post-war America was in fact first visualised, then designed in times of Depression and war. Loewy, who died in 1986 at the age of 93, would proba- bly have shrugged that off as coincidence.

. . and here's one of me just before we left Lilliput.'

Previous page

Previous page