CHESS

Master class

Raymond Keene

the 1960s and early 1970s were a period of wasted talents. The most notable exam- ple was the tragic case of world champion Bobby Fischer who, on what appeared to be the verge of a brilliant career as champion, simply renounced chess. The syndrome extended to Tigran Petrosian who, though he twice won the world championship in 1963 and 1966, never realised his true potential. In his case, the handicap was excessive diffidence, which caused him to agree far too many anodyne draws. Mikhail Tal, who seemed set to dominate the chess world when he defe- ated Botvinnik to become champion in 1960, foundered on ill-health. Although he remains a formidable competitor, he suf- fered a debacle at the hands of Botvinnik in the 1961 revenge match, and since then he has never again challenged for the supreme title. Finally, Boris Spassky be- came a casualty when Fischer knocked the guts out of him in their 1972 match. Fischer was a monomaniac, up to that point a virtually monk-like recluse, devoted en- tirely to the 64 squares. As Spassky lamented during his 1972 match against Fischer, he himself had a wife and children and enjoyed music and literature. Spassky simply could not match Fischer's scorching concentration, and having flown too close to the chess sun, Spassky was burnt out himself.

Two books celebrate the best years of Tal and Spassky, Mikhail Tal's Best Games of Chess, 1951-1960, written by the En- glish Olympic player Peter Clarke, and Spassky's Hundred Best Games 1949-1972, written by Bernard Cafferty, the editor of the British Chess Magazine. Long out of print, these volumes have now been reis- sued by Batsford as Mikhail Tal — Master of Sacrifice and Boris Spassky — Master of Tactics. Two samples of play show what awaits the potential reader.

Spassky — Bronstein: Soviet Championship 1960; King's Gambit.

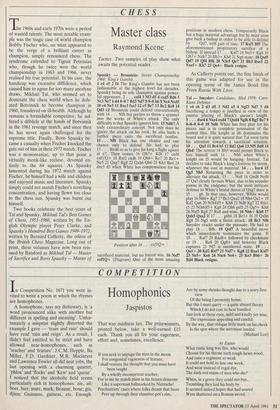

1 e4 e5 2 f4 The King's Gambit has not been fashionable at the highest level for decades, Spassky being its sole champion against power- ful opponents. 2 . . . exf4 3 Nf3 d5 4 exd5 Bd6 5 Nc3 Ne7 6 d4 0-0 7 Bd3 Nd7 8 0-0 h6 9 Ne4 Nxd5 10 c4 Ne3 11 Bxe3 fxe3 12 c5 Be7 13 Bc2 Re8 14 Qd3 e2 Bronstein could defend conventionally with 14 . . . Nf8 but prefers to throw a spanner into the works of White's attack. The only difficulty is that Spassky ignores him. 15 Nd6!! A truly extraordinary concept. Not only does he ignore the attack on his rook, he also hurls a further piece onto the sacrificial bonfire. 15 . . . Nf8 Black has one chance and one chance only to defend. He had to play 15 . . . Bxd6 so as to give his king a flight square at e7. Then comes 16 Qh7+ Kf8 17 cxd6 exfl/Q+ 18 Rxfl cxd6 19 Qh8+ Ke7 20 Rel + Ne5 21 Qxg7 Rg8 22 Qxh6 Qb6 23 Khl Be6 24 dxe5 d5 when White has compensation for his Position after 16 . . . exf1Q+ sacrificed material, but no forced win. 16 Nxf7 exf1Q+ (Diagram) One of the most amazing positions in modern chess. Temporarily Black has a huge material advantage but he must soon give back a bishop in order to be able to defend by . . . Qd7, with gain of time. 17 Rxfl Bf5 The aforementioned propitiatory sacrifice of a bishop. If instead 17 . . . Kxt7 18 Ne5+ Kg8 19 Qh7+ Nxh7 20 Bb3+ Kh8 21 Ng6 mate. 18 QxfS Qd7 19 Qf4 Bf6 20 N3e5 Qe7 21 Bb3 BxeS 22 NxeS+ Kh7 23 Qe4+ Black resigns.

As Cafferty points out, the fine finish of this game was adapted for use in the opening scene of the James Bond film From Russia With Love.

Tal — Smyslov: Candidates, Bled 1959; Caro- Kann Defence.

1 e4 c6 2 d3 d5 3 Nd2 e5 4 Ngf3 Nd7 5 d4 Sacrificing a tempo is justified in view of the passive placing of Black's queen's knight. 5 . . . dxe4 6 Nxe4 exd4 7 Qxd4 Ngf6 8 Bg5 Bel 9 0-0-0 0-0 10 Nd6 White has free play for his pieces and is in complete possession of the central files. His knight at d6 dominates the board and it is quite natural that Tal soon turns his attention towards a sacrificial solution. 10 . . . Qa5 11 Bc4 b5 12 Bd2 Qa6 13 Nf5 Bd8 14 Qh4! The retreat 14 Bb3 would permit Black to free himself with 14 . . . Nb6 when White's knight on f5 would be hanging. Instead, Tal decides to take Black's king's fortress by storm, whatever the cost in material. 14 . . . bxc4 15 Qg5 Nh5 Returning the piece in order to alleviate the attack. 15 . . . Ne8 16 Qxd8 Nef6 17 Qa5 clearly favours White, due to his sounder pawns in the endgame, but the most intricate defence to White's brutal threat of Qxg7 mate is 15 . . . g6. In that case, however, White would play 16 Nh6+ Kg7 17 Bc3 Qxa2 18 Nh4 Qal+ 19 Kd2 Qa6 20 N(h4)f5+ Kh8 21 Nd6 Kg7 22 Rfel c5 23 N(h6)f5+ Kg8 24 Qh6 gxf5 25 Qg5+ Kh8 26 Nxf5 Rg8 27 Re8 and wins. 16 Nh6+ Kh8 17 QxhS Qxa2 If 17 . . . gich6 18 Bc3+ f6 19 Qxh6 Rg8 20 Ng5 with a fierce attack. 18 Bc3 Nf6 Smyslov cracks under the pressure. He had to play 18 . . Bf6. 19 Qxf7 A beautiful move which immediately terminates the game. If 19 . . . Rxf7 20 Rxd8+ followed by checkmate or 19 . . . Re8 20 Qg8+ and however Black captures 21 Nf7 is smothered mate. 19 . . . Qal+ 20 Kd2 Rx17 21 Nxf7+ Kg8 22 Rxal Kx17 23 Ne5+ Ke6 24 Nxc6 Ne4+ 25 Ke3 Bb6+ 26 Bd4 Black resigns.

Previous page

Previous page