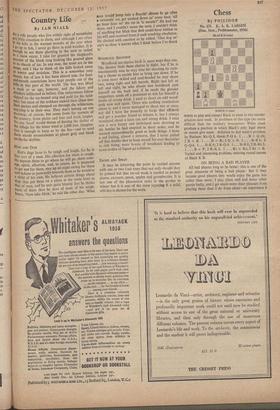

Chess

No. 131. K. A. K. LARSEN (Hon. Men., Problemnoter, 1956)

Will 1 F. (5 men)

wiirrE to play and compel Black to mate in two moves: solution next week, In problems of this type (no more difficult than the ordinary two-mover) White must produce a position in which Black's only legal move or moves give mate. Solution to last week's problem by Poulsen: Kt-Q 8, threat P-Q 6. I B x Q ch; 2R x B. 1 ...B x R; 2 Q x P, 1 . . . B-B 6; 2 Q-Q 6. I B-K 6; 2 R-Q 4. I B-B 8; 2 R-Kt 2. 1 ... B x P; 2 R-K 8. 1 . Kt x Kt; 2 Kt x B. Varied and interesting problem, centring round moves of Black K B.

ON B.EING A BAD PLAYER

All bad players long to be better: this is one of the great pleasures of being a bad player. But if they became good players they would enjoy the game less rather than more; I play chess well and many other games badly, and I get much more sheer pleasure from playing these than I do from chess—an experience I

am quite sure is widely shared in all games and sports. Why is this?

There are so many reasons I hardly know where to begin, so to be in good company I will start with two remarks by the best of all essayists, Hazlitt, in 'Whether Genius is conscious of its powers?' These are, first, 'He who comes up to, his own idea of greatness, must always have had a very low standard of it in his mind,' and second, 'It is only where our incapacity begins that we begin to feel the obstacles, and to set an undue value on our triumph over them.' When the rabbit thinks, 'How wonderful to play like Smyslov,' he is imagining that; if he were Smyslov, he would continue to admire his skill as much as he does now—but he wouldn't: he would take for granted what he could do and be more conscious and critical than ever of what he could not do. The weak player who wins a game full of unnoticed blunders on both sides will view his victory with more unquestioning satisfaction than the master whose deeper vision is likely to see flaws in even the finest victory. An even more serious drawback that the master suffers from is that the game is. important to him in a much more fundamental way than can be the case for the most enthusiastic rabbit; because he is so good and has put so much of his life into chess (he will not be a master if he has not), defeat means a painful loss of 'face' in his own eyes and those of the chess world as a whole—this makes an important game far more of a purgatory than a pleasure.

Then why try to become a good player at all? For three reasons. First, because it is impossible not to do so; it is not in human nature to playa game and not try, however feebly, to get better. Secondly, because the good player, although he may get less pleasure than the bad one, lives more intensely while he exercises his skill, and this is something intrinsically worth while whether it is pleasant or not. Finally, because whether or not it is agreeable to be a good player, one of the greatest of all satisfactions is to be improving; in short, 'it is better to travel hopefully in the right direction] than to arrive.'

Previous page

Previous page