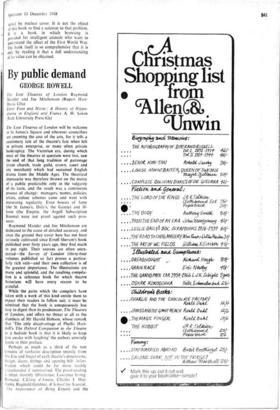

By public demand

GEORGE ROWELL

The Lost Theatres of London Raymond Mander and Joe Mitchenson (Rupert Hart- Davis 126s) Enter Foot and Horse : A History of Hippo- drama in England and France A. H. Saxon (Yale University Press 62s) The Lost Theatres of London will be welcome in St James's Square and wherever councillors are counting the cost of the arts, for it tells a cautionary tale of the theatre's fate when left to private enterprise, or more often private bankruptcy. The Victorian era, during which most of the theatres in question were lost, saw the end of that long tradition of patronage (from church, trade guild, crown, court and city merchant) which had sustained English drama from the Middle Ages. The theatrical impresario was therefore thrown on the mercy of .a public predictable only in the vulgarity °Pits taste, and the result was a continuous process of change: managers; names, 'policies, artists, colour schemes came and. went with depressing regularity. Even houses of fame (thei St James's, Daly's, the Gaiety) and ill- fame (the Empire, the Argyll Subscription Moms) were not proof against such pres- sures: 'Raymond Mander and Joe Mitchenson are dedicated to the cause of detailed accuracy, and since' the ground they cover here has not been seriously cultivated since Erroll Sherson's book published over forty years ago, they find much to put right. Their sources are often unex- pected—the Survey of London (thirty-four volumes published so far) proves a particu- larly rich vein—and their own collection is of the greatest importance. The illustrations are many and splendid, and the resulting compila- tion is a reference book for which theatre historians will have every reason to be grateful.

While the pains which the compilers have taken with a work of this kind entitle them to expect their readers to follow suit, it must be admitted that the book is conspicuously less easy to digest than its predecessor, The Theatres of London, and offers no threat at all to the slumbers of Mr Harold Hobson, whose remark that 'The only disadvantage of Phyllis Hart- foil's The Oxford Companion to the Theatre

as a bedside book is that it is likely to keep you awake with laughing' the authors unwisely quote in their preface.

Perhaps as much as a third of the text consists of verbatim description (mostly from the Era and Stage) of each theatre's dimensions, design, decor, fittings and opening bill—infor- mation which could be far more readily apprehended if summarised. The proof-reading is often slovenly (Diocletian, Lawrence Irving, Bernand. L'Elisia d'Amore, Charles J. Mat- theWs, Reginald Gerdner, A School for Scandal, The importance of Being Ernest). and the

authors tend to cast aside their customary accuracy in obiter dicta. Thus we are told Davenant (who died in 1668) 'took the name with him to his new Playhouse, designed by Sir Christopher Wren, opened in 1671,' and, despite the popularity in England of Johann Strauss, Suppe, Millocker and others, The Merry Widow, it is claimed, 'marked the intro- duction of Viennese operetta to London.' Even stranger is the comment on p. 141 that 'con- secutive runs had commenced in the theatre in the sixties,' although as early as 1810 The Blood Red Knight ran for 175 performances at Astley's, and runs of one hundred nights or more were regularly, though not frequently, achieved thereafter.

Asfley's, being a `transpontine' or. Surreyside theatre, is excluded from The Lost Theatres of London, but it was here and at the Royal Circus, its rival, that the 'hippodrama' of which Mr Saxon writes chiefly held sway. This mulish breed of entertainment, a cross between circus and theatre, though anathema to the genuine circus enthusiast, captured the imagination of the early nineteenth century audience and threw up such heroes as Philip Astley himself and Andrew Ducrow, famous for 'cut the cackle' (more accurately 'dialect' for 'dialogue,' it seems) 'and come to the 'osses.' Enter Foot and Horse borrows its title from Pope, but covers French equestrianism as well as English and shows convincingly how the Parisian ver- sion kept alive memories of the Napoleonic gloire miliiaire. Like all writers on Victorian drama, the author is sometimes defeated by the intractability of a purely visual genre on the printed page, but some of the more improbable episodes make lively reading. There was, for

example, an . equestrian Macbeth on which Punch commented:

'Nothing can be finer, more novel, too, than the appearance of Lady Macbeth in the sleep- ing scene on a Shetland pony. The quietude, the docility of the animal, shews that it perfectly enters into the feelings of the rider, and thereby evinces, for a pony, the most extraordinary sym- pathy with the profundities of SHAKSPEARE.'

The last years of 'hippodrama' were, of course, dominated by Adah Isaacs' Menlcen in Mazeppa, but the heroine of the book for me is a certain Charlotte Crampton, who played Richard III on horseback and was, according to a distinguished American historian, 'the only woman I ever saw who could satis- factorily impersonate such arduous characters as Richard III, Iago,-- Shylock, and Hamlet,' though, alas, her performance in the other three roles seems to have been wholly pedestrian.

Previous page

Previous page