ARTS

Bilbao's imperial masterpiece

Martin Gayford is impressed by the flamboyantly eccentric new Guggenheim Museum Aone walks down Calle Iparraguirre, a perfectly normal street in central Bilbao, an extraordinary sight looms up. Billowing curves, and jutting overhangs of titanium, shining in the sun; a vast baroque jumble of forms, twisting and undulating unexpected- ly beyond the perspective of foursquare 19th-century and drab modern blocks. It looks at first glance like some weird craft just landed from a planet circling Andromeda. In fact, this is the Guggen- heim Museum Bilbao — or, if you prefer it in Basque, the Guggenheim Bilbao Museoa — the masterpiece to date of the Los Angeles-based architect Frank 0. Gehry, and latest manifestation of a late 20th-cen- tury phenomenon: the imperial museum.

Once upon a time, museums were found- ed in imperial centres. Napoleon took all the art in Europe — or as much as he could possibly shift — to the Louvre, whence after his defeat most of it was transported back to where it came from. I vividly recall the tone of respect in which a group of Japanese I once took round the British Museum declared, Ilhhar! England must once have been very powerful to take all these things from other countries!' Now all that has changed, and it is the museum itself that has become imperial, sending out off-shoots and outposts to the furthermost reaches of the world. In exact reverse of the Napoleonic procedure, the works of art are sent out from the centre to patrol the world.

We have seen something of the sort in this country with the ever-proliferating Tate (on Millbank, in St Ives, Liverpool and soon Bankside). But the Tate is small potatoes compared to the international expansionism of the Guggenheim. Once that museum was confined to the famous building by Frank Lloyd Wright on Fifth Avenue in New York (famous not only for its spiral design, but also as a disastrously ill-suited space for the display of pictures).

Then, in the Seventies, it took over the Peggy Guggenheim Collection in Venice. Under its present director, Thomas Krens, its Upper East Side headquarters are being substantially and controversially expanded. A few years ago, it threw out a new branch in downtown SoHo (the Guggenheim SoHo). Now it has leapt the Atlantic to Berlin, where the Guggenheim Deutsch- land has just opened, and also, but spectac- ularly and surprisingly, the Guggenheim Bilbao.

Naturally, Krens's Napoleonic progress has not gone uncriticised, especially when several paintings by artists such as Chagall were sold to help finance a collection for yet another project — a huge museum of contemporary art to be housed in a disused textile factory in rural Massachusetts (due to open next year). There are, indeed, some dubious aspects of the imperial Guggen- heim, of which more below. But the first point to register is that as a building and a project the whole is a stunning success.

The building — and Gehry's other previ- ous works — also have their detractors. Fundamentalist early modernists, of whom there are quite a lot still around, among architects, are peeved that the design is not a Mies van der Rohe box — in fact, there is scarcely a straight line to be seen. Others carp about its lack of relation to its sur- roundings, which consist, apart from Calle Iparraguirre, of a large lorry-park and sus- pension bridge on a stretch of post-indus- trial dereliction beside the River Nervien.

Both objections dwindle away when one sees it on the spot. Though perhaps the wildest, most completely and extravagantly bizarre structure ever built, even in Spain, Gehry's building is not without a context either cultural or environmental.

Indeed, if his building looks like anything — and the mind flails in the attempt to find an analogy — it resembles some of the more outré of the creations of the Catalan master of the mystical art nouveau, Antoni Gaudi. Gehry's architecture, like Gaudi's, is based on natural forms; in this case snakes, fish and sails just taking the wind (one wonders what Gaudi might have come up with given computer-aided design and the ability to conjure walls from 1/3 mil- limetre titanium skin). At any rate, Gehry's creation looks completely at home in the land of over-the-top gothic, baroque and art nouveau extravaganza. It also looks splendid on the river bank, activating the site in the way that a cathedral, sprouting towers, can animate a city.

It has stimulated Bilbao in another sense, too. Previously a rather drab indus- trial spot — a sort of Basque Middlesbor- ough — now the place is full of tourists. In fact, the queues at the Guggenheim when I was there — admittedly on a weekend but- tressed by two Spanish national holidays — made it almost impossible to get into the place.

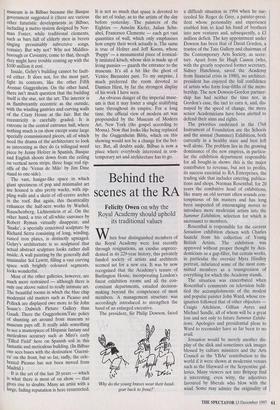

Thomas ICrens's theory is that today, in the era of mass travel, the museum doesn't have to be in a great centre. It can be virtu- ally anywhere, and the public will travel to it. Clearly, so far, the theory works. The A fantastic and meticulous building: the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, photographed by Aitor Ortiz museum is in Bilbao because the Basque government suggested it (there are various other futuristic developments in Bilbao, including a metro system designed by Nor- man Foster, while traditional elements, such as bars full of elderly men in berets singing presumably subversive songs, remain). But why not? Why not Middles- borough or Coventry, come to that, though they might have trouble coming up with the $100 million it cost.

Inside, Gehry's building cannot be fault- ed either. It does not, for the most part, fight its contents, like the other Fifth Avenue Guggenheim. On the other hand, there isn't much question that the building itself is the star, not the art. The interior is as flamboyantly eccentric as the outside, with the winding gantries and curving walls of the Crazy House at the fair. But the eccentricity is carefully graded. It is extreme in the central entrance hall, where nothing much is on show except some large specially commissioned pieces, all of which need the drama of the architecture to look as interesting as they do (a trilingual word piece by Jenny Holzer in Spanish, Basque and English shoots down from the ceiling on vertical neon strips, three huge red rip- offs of the 'Venus de Milo' by Jim Dine stand to one side).

The vast, hangar-like space in which giant specimens of pop and minimalist art are housed is also pretty wacky, with rip- pling walls and a skein of off-centre arches in the roof. But again, this theatricality enhances the half-acre works by Warhol, Rauschenberg, Lichtenstein et al. On the other hand, a trio of all-white canvases by Robert Ryman virtually disappear, and 'Snake', a specially conceived sculpture by Richard Serra consisting of long, winding, rusted iron plates, is distinctly upstaged. Gehry's architecture is so sculptural that actual abstract sculpture looks rather dull inside. A wall painting by the generally dull minimalist Sol Lewitt, filling a vast curving space with brightly coloured segments, looks wonderful.

Most of the other galleries, however, are much more restrained — although there is only one alcove suited to really intimate art. The beautiful rooms in which the blue chip modernist old masters such as Picasso and Pollock are displayed owe more to Sir John Soane's Dulwich Picture Gallery than Gaudi. There the Guggenheim/Tate policy of shunting art around from museum to museum pays off. It really adds something to see a masterpiece of Hispanic fantasy and meticulous accuracy such as Miref s early 'Tilled Field' here on Spanish soil in this fantastic and meticulous building. (In Bilbao one sees buses with the destination `Guerni- ca' on the front, but so far, sadly, the cele- brated Picasso has not been moved from Madrid.) It is the art of the last 20 years — which is what there is most of on show — that gives rise to doubts. Many an artist with a large, fading reputation is here resurrected. It is not so much that space is devoted to- the art of today, as to the artists of the day before yesterday. The painters of the Eighties — Anselm Kiefer, Julian Schn- abel, Francesco Clemente — each get vast quantities of wall, which only emphasises how empty their work actually is. The same is true of Holzer and Jeff Koons, whose 'Puppy' — a monumental piece of ironical- ly imitated kitsch, whose skin is made up of living pansies — guards the entrance to the museum. It's all a bit like the ghost of Venice Biennales past. To my surprise, I much preferred the room devoted to Damien Hirst, by far the strongest display of his work I have seen.

An obvious danger of the imperial muse- um is that it may foster a single stultifying taste throughout its empire. For a long time, the official view of modern art was propounded by the Museum of Modern Art, New York (the gospel according to Moma). Now that looks like being replaced by the Guggenheim Bible, which on this showing would not be a change for the bet- ter. But, all doubts aside, Bilbao is now a place where everybody interested in con- temporary art and architecture has to go.

Previous page

Previous page