Yesterday in Bohemia

CAFE ROYAL. By •Guy Deghy and Keith Waterhouse. (Hutchin- son, 21s.) 'I REMEMBER Romano's, just as it- used to be'—this was a line, often repeated, in a song sung at a revue a few years ago by Cyril Ritchards, which had a great success, and the nostalgic lilt of the music was not immediately forgotten, especially by me, who in fact do 'remember Romano's, just as it used to be.' It was in those happy days, when England's destinies were guided by the genial glow of good King Edward's large cigar, that I first visited Romano's, joining the throng of stage-door Johnnies, and it was there that in my late teens I ordered my second bottle of cham- pagne. The first bottle was ordered by me at the Café Royal on my seventeenth birthday, while still at Rugby, and I felt that the combination of the Café Royal atmosphere and my being already man enough to order champagne was a delightful blending. It was not the first champagne I had ever drunk—that had been on Mafeking night—but it was the first I had ever ordered off my own bat and I felt proud of myself.

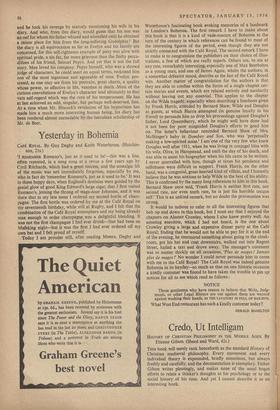

Today I am prouder still, after reading Messrs. Deghy and Waterhouse's fascinating book evoking memories of a landmark in London's Bohemia. The first remark I have to make about this book is that it is a kind of vade-mecum of Bohemia at the turn of the century in which references can be found to most of the interesting figures of the period, even though they are not strictly connected with the Cafe Royal. The second remark I have to make is to congratulate the publishers on their choice of illus- trations, a few of which are really superb. Others are, to me at any rate, remarkably interesting, especially one of Max Beerbohm as a young man, and one of James Agate, whdm the authors, in a somewhat defeatist mood, describe as the last of the Café Royal wits. Another matter of congratulation for the authors is that they are able to confine within the limits of a single chapter cer- tain stories and events, which are related entirely and succinctly without leaving out any essential. This applies to the chapter on the Wilde tragedy, especially when describing a luncheon given by Frank Harris, attended by Bernard Shaw, Wilde and Douglas as guests, at which Harris attempted (in genuine loyalty to his friend) to persuade him to drop his proceedings against Douglas's father, Lord Queensberry, which he might well have done had it not been for poor misguided Douglas's efforts to goad him on. The latter's behaviour reminded Bernard Shaw of Mrs. McStinger's baby in Dombey and Son, who was 'perpetually making a low-spirited noise.' I am-one of the very few who knew Douglas well after 1911, when he was living in conjugal bliss with his wife, Olive, in Hampstead, and until the day of his death, and was able to assist his biographer when his life came to be written. I never quarrelled with him, though at times his petulance and selfishness were difficult to support. Frank Harris, on the other hand, was a congenial, great-hearted kind of villain, and I honestly believe that he was anxious to help Wilde to the best of his ability. This is confirmed by the many long references to him in this book. Bernard Shaw once said, 'Frank Harris is neither first rate, nor second rate, nor even tenth rate, he is just his horrible unique self.' This is an unkind remark, but no doubt the provocation was strong.

It would be tedious to refer to all the interesting figures that bob up and down in this book, but I must say that I enjoyed the chapters on Alesteir Crowley, whom I also knew pretty well. An amusing anecdote, which I had not heard, is the one about Crowley giving a large and expensive dinner party at the Café Royal; finding that he would not be able to pay for it at the end of the evening, he murmured something about going to the cloak- room, got his hat and coat downstairs, walked out into Regent Street, hailed a taxi and drove away. The manager's comment was to mutter thickly on all occasions, 'Plus de mages! Jamais plus de mages !' No wonder I could never persuade him to come with me to the Café Royal! The Café Royal was indeed genuine Bohemia in its heyday—so much so that on one historic occasion a kindly customer was found to have taken the trouble to pin up notices for all to see which read as follows : NOTICE

Those gentlemen who have reason to believe that Writs, Judg- ments, or other Legal Blisters are out against them are warned against washing their hands, as THE LAVATORY IS FULL OF BAILIFFS. What West End restaurant has such a kindly customer today?

GERALD HAMILTON

Previous page

Previous page