Architecture

The Building of an 18th-Century City: Bath Spa (RIBA Heinz Gallery, till 3 August)

Beauty of Bath

Alan Powers

For all its tourist coaches and twee shops, Bath remains a glorious place. `Goodbye to old Bath! We who loved you are sorry/They're carting you off by devel- oper's lorry,' wrote John Betjeman in 'The Newest Bath Guide', in the metre of the Georgian versifier Christopher Ansty, but although what has gone cannot be returned, there is nowhere else in England with the same concentration of good build- ing, such as one finds in an Italian hill town.

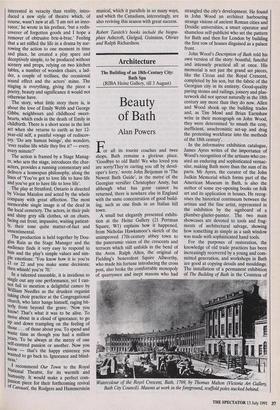

A small but elegantly presented exhibi- tion at the Heinz Gallery (21 Portman Square, W1) explains how it happened, from Nicholas Hawksmoor's sketch of the unimproved 17th-century abbey town to the panoramic vision of the crescents and terraces which still unfolds in the bend of the Avon. Ralph Allen, the original of Fielding's benevolent Squire Allworthy, who made his fortune introducing the cross post, also broke the comfortable monopoly of quarrymen and inept masons who had strangled the city's development. He found in John Wood an architect harbouring strange visions of ancient Roman cities and Druidic universities, a smart operator and shameless self-publicist who set the pattern for Bath and then for London by building the first row of houses disguised as a palace front.

John Wood's DescnPtion of Bath told his own version of the story: boastful, fanciful and intensely practical all at once. His memorial is not just the grand set pieces, like the Circus and the Royal Crescent, completed by his son, but the fabric of the Georgian city in its entirety. Good-quality paving stones and railings, joinery and plas- terwork did not sprout naturally in the 18th century any more than they do now. Allen and Wood shook up the building trades and, as Tim Mowl and Brian Earnshaw write in their monograph on John Wood, they were determined 'to smash the cosy, inefficient, anachronistic set-up and drag the protesting workforce into the methods of the 18th century'.

In the informative exhibition catalogue, James Ayres writes of the importance of Wood's recognition of the artisans who cre- ated an enduring and sophisticated vernac- ular, making Bath more than the sum of its parts. Mr Ayres, the curator of the John Judkin Memorial which forms part of the American Museum in Bath, is also the author of some eye-opening books on folk art and its application in houses. He recog- nises the historical continuum between the artisan and the fine artist, represented in the exhibition by the signboard of a plumber-glazier-painter. The two main showcases are devoted to tools and frag- ments of architectural salvage, showing how something as simple as a sash window was made with sophisticated hand tools.

For the purposes of restoration, the knowledge of old trade practices has been increasingly recovered by a young and com- mitted generation, and workshops in Bath are good at copying details and mouldings. The installation of a permanent exhibition of The Building of Bath in the Countess of Watercolour of the Royal Crescent, Bath, 1769, by Thomas Malton (Victoria Art Gallery, Bath City Council). Masons at work in the foreground, scaffold poles stacked behind. Huntingdon's Chapel, of which the Heinz show is a foretaste, will educate both potential artisans and, one hopes, patrons.

The study and practice of traditional building techniques has importance for the current development of architecture. Too few of those involved in building seem to have the eye for such simple things as mor- tar joints in stone or brick or the difference between limewash and cement paint. These pleasures of the eye are intimately linked to the unseen ecological benefits of certain traditional techniques, but only a few archi- tects like David Lea take account of the long-term consequences of their buildings in the use of energy and resources. There are still only a few clients — such as Cirencester Agricultural College, until its recent disgraceful dismissal of Lea in the middle of a project — who appreciate the long-term view and are prepared to take risks and pay a little extra for it.

Designing with these priorities by no means predicates 'traditional' forms, and is the opposite of the cynical veneering of his- torical styles over standard modern con- struction which has inevitably been practised in Bath. At present, techniques and standards used in conservation work are hardly ever applied to new building, and we await new Woods and Aliens to mobilise the artisans and return them to their deserved place at the centre of the building operation.

Previous page

Previous page