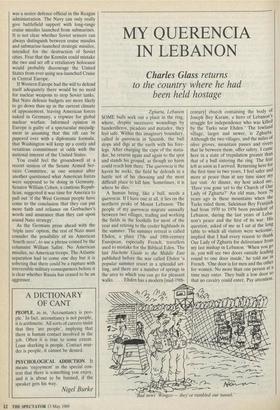

MY QUERENCIA IN LEBANON

Charles Glass returns

to the country where he had been held hostage

Zgharta, Lebanon SOME bulls seek out a place in the ring, where, despite successive woundings by banderilleros, picadors and matador, they feel safe. Within this imaginary boundary, called la querencia in Spanish, the bull stops and digs at the earth with his fore- legs. After charging the cape of the mata- dor, he returns again and again to the spot and stands his ground, as though no harm could reach him there. The querencia is the haven he seeks, the field he defends in a battle not of his choosing and the most difficult place to kill him. Sometimes, it is where he dies.

A human being, like a bull, needs a querencia. If I have one at all, it lies on the northern peaks of Mount Lebanon. The people of my querencia migrate annually between two villages, trading and working the fields in the foothills for most of the year and retiring to the cooler highlands in the summer. The summer retreat is called Ehden, a place 17th- and 18th-century European, especially French, travellers used to mistake for the Biblical Eden. The last Hachette Guide to the Middle East published before the war called Ehden 'a popular summer resort in a splendid set- ting, and there are a number of springs in the area to which you can go for pleasant walks. . . . Ehden has a modern [mid-19th- century] church containing the body of Joseph Bey Karam, a hero of Lebanon's struggle for independence who was killed by the Turks near Ehden.' The lowland village, larger and newer, is Zgharta. Although the two villages, and the miles of olive groves, mountain passes and rivers that lie between them, offer safety, I came here in a state of trepidation greater than that of a bull entering the ring. The fear left as soon as I arrived. Returning here for the first time in two years, I feel safer and more at peace than at any time since my last visit. At dinner, my host asked me, 'Have you gone yet to the Church of Our Lady of Zgharta?' An old man, born 79 years ago in these mountains when the Turks ruled them, Suleiman Bey Franjieh had from 1970 to 1976 been president of Lebanon, during the last years of Leba- non's peace and the first of its war. His question, asked of me as I sat at the long table to which all visitors were welcome, implied that I had every reason to thank Our Lady of Zgharta for deliverance from my last mishap in Lebanon. 'When you go in, you will see two doors outside leading round to one door inside,' he told me in French. 'One door is for men and the other for women. No more than one person at a time may enter. They built a low door so that no cavalry could enter. Pay attention.

'Bad news' Wingco — they've rumbled our tunnel.' Whet the men of the village wbuid go out to defend it, they would put the women and children in the church. Then they were free to fight.' Zgharta and thden, as well as the Cedars and Kahlil Gibran's village of Bcharre, stand at the northern rim, of Maronite Lebanon, in the cradle of fheir culture along, the kadisna Valley. They ate closer, than the rest of Maronite Lebanon fo Syria,, both physically and politically. They lie just outside Maronite 'free Leba- non' Whose domination is shared by General Michel Aoun, the Lebanese army and the militia known as the Lebanese Forces. Syrian forces are all around the north, and for that reason the northern Maronite mountain is at peace. Yet, when the Maronites of the north see Syrian gunners on their soil firing artillery shells at their co-religionists and countrymen to the south, their resentment against the Syrians grows.

President Franjieh made an alliance in 1976 with Syria, mainly with his old friend the Syrian President, for a Syrian interven- tion to help Lebanon's Christians against the Palestinians and their allies among what the French press called the Islamo- Progressistes. The United States and the Christian leaders Of that time, from the Phalangist Party to the leaders of what catne to be called the Lebanese Forces, co-operated in the Syrian intervention. The Syrians were supposed to vanquish the Maronites' enemies for them, return dominion over the country to a Maronite president and army and then leave. Syria did none of those things. Like most allies invited into a smaller country to assist in a local conflict, the Syrians stayed. The Maronites, with the exception of President Franjieh who was a kind of Arab national- ist, turned to Israel. When President Fran- jieh broke ranks with the pro-Israelis, the Phalangists sent raiders to Ehden to mur- der his older son, Tony, killing Tony's wife and baby daughter in the process. The leader of the attack was a young man from nearby Becharre named Samir Geagea, who now heads the Lebanese Forces mili- tia.

Most CliriStians and many Muslims now want the Syrians out, even if their depar- ture would not end Lebanon's problems. Syria's allies in the country are aware of the anti-Syrian groundswell exposed by the foolhardy actions of General Michel Aoun, who provoked heavy Syrian shelling of the Marbnite heartland. Many people ask, `What alternative did Aoun have? How else can we get the Syrians out?'

A Greek Orthodox friend, from another part of the north, said Aoun was trying only to delay further the presidential elec- tions that failed to take place last summer. `First, he fought the Lebanese forces,' my friend, himself a politician, said. 'Then he fought the Muslims and the Syrians. So long as he is fighting, there can be no elections. He knows that if there were elections, he would lose and a new presi- dent would dismiss him as commander of the army.' It seemed General Aoun was like any other Arab leader, a general seizing power in a military coup and forestalling elections until he could win. At last, the Maronites were making their little Marounistan an Arab country. It is hard for the Christians here to accept the latest round of fighting without complaint, and many of them are proud to say their sons are in Beirut as officers in General Aoun's army. News of the shelling is on all the radio stations, and first-hand information is only a telephone call away. I called a friend in Ashrafieh, a Maronite quarter of east Beirut that has taken many of the Syrian shells. 'Can't you hear the shelling over the telephone?' she asked me. She refused to go downstairs into their shelter, because her sister and her sister's children made too much noise. Nor could she drive north to visit us, because the Syrians had closed the road. So, she read in her room and listened to the shells fall. She said it was an interesting time.

Except for conversation about the war, Zgharta is an idyll of peace and tranquilli- ty. I walked through streets and fields undisturbed, until my cousin Violette re- minded me, Tu dois remercier Notre Dame de Zgharta, Charles. Elle t'a !there.' With suggestions from both my host and my pious cousin weighing on my conscience, I had little choice but to go in the morning to the old church. It looked like a stone cube in the middle of the oldest quarter in the village, surrounded by old Tuscan-style stone houses. I ducked my head to walk through the outer door, then turned to enter the inner door to the church itself. The inviolate citadel was cool and dark, except for sun shining through the slits above, like the openings for bowmen in Crusader castles. Square stone columns stood between the floor and the cobbled ceiling, as though this were the earliest or most primitive of Gothic structures. Above the altar was an oil portrait of Our Lady of Zgharta, surrounded by roses and clouds, a painting that had been there when my grandmother was baptised a century ear- lier. Her father had just died. According to her, he had returned from Mexico, where he fought in the revolution, and insisted on fighting the Turks, who killed him. Other relations said they thought he had been killed in a feud, easy to understand in a village as plagued by vendetta as any in Sicily. Her mother married again, left her first husband's lands behind at a time the Turks were starving out the Maronites and took her young daughter to the new world. Kneeling before the altar, I prayed for her as she had so often prayed for me.

Outside, my driver-cum-bodyguard was waiting. I felt a little like Michael Corleone in The Godfather, returning to Sicily under the protection of one of its more illustrious families and wandering the countryside with guards who carried the lupara to keep away, not wolves, but human predators. We went to a little eucalyptus grove by the river. On both banks were small outdoor restaurants, and we sat in one to drink Turkish coffee. The water gushed out of a flour mill upriver, past us to a bend near fields of wheat and out of sight on its way to the sea near Tripoli. The people of Zgharta call it the River Merdishia, but further upriver, it is the Zaraya. In Tripoli, they call it the Abu Ali. No one seemed to mind that maps called the entire river, from source to mouth, the Rashin. This was the laissez-faire Lebanon that the war was destroying, a country its people viewed in different ways, in which they lived by different customs, and where they could worship God in any way they chose or not at all.

At President Franjieh's dinner table, laden with dozens of different foods, some- one brought me a glass of arak, made at home of distilled grape and aniseed, with water and ice. I was served kibbe naye, a lamb tartare made with cracked wheat and onion, just as my grandmother used to make for me before she died. President Franjieh proposed a toast welcoming me back. Next to him was young Suleiman, the son of his late son, Tony. Tony's younger brother, Robert, said I had come home. Robert's sister Lamia noticed that I could not speak, and she said to me, 'Don't worry, Charlie. We're all survivors.'

I hate to leave, but there are other survivors — of torture, of chemical war, of long imprisonment — waiting hundreds of miles to the east on Syria's border with Iraq. They want the world to know about their plight, but they do not understand that the world will do nothing. Their querencias have been destroyed, and it is harder for them than it is for me to return.

Previous page

Previous page