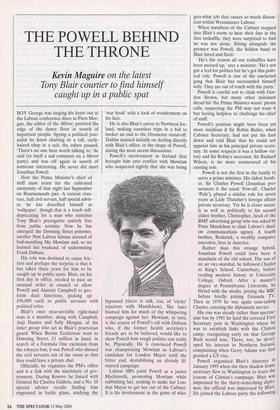

THE POWELL BEHIND THE THRONE

Kevin Maguire on the latest

Tony Blair courtier to find himself caught up in a public spat

BOY George was singing his heart out at the Labour conference disco as Piers Mor- gan, the editor of the Mirror, prowled the edge of the dance floor in search of important people. Spying a political jour- nalist he knew chatting to a tall, curly- haired chap in a suit, the editor paused. `There's no one here worth talking to,' he said (in itself a sad comment on a Mirror party) and was off again in search of someone interesting. He never did meet Jonathan Powell.

How the Prime Minister's chief of staff must yearn for the cultivated anonymity of that night last September on Bournemouth pier. A curious crea- ture, half civil servant, half special advis- er, he has described himself as `wallpaper', though that is a touch self- deprecating for a man who exercises Tony Blair's prerogative entirely free from public scrutiny. Now he has emerged: the Downing Street poisoner, another New Labour hitman accused of bad-mouthing Mo Mowlam and, so we learned last weekend, of undermining Frank Dobson.

His role was destined to cause fric- tion and perhaps the surprise is that it has taken three years for him to be caught up in public spats. Blair, on his first day in office, needed to pass an unusual order in council to allow Powell and Alastair Campbell to per- form dual functions, picking up £96,000 each as public servants with political roles.

Blair's once near-invisible right-hand man is a member, along with Campbell, Anji Hunter and Sally Morgan, of the inner group who act as Blair's praetorian guard. When Bernie Ecclestone went to Downing Street, £1 million in hand, in search of a Formula One exclusion from the tobacco ban, it was Powell who shooed the civil servants out of the room so that they could have a private chat.

Officially, he organises the PM's office and is a link with the machinery of gov- ernment. During Kosovo he liaised with General Sir Charles Guthrie, and a No. 10 special adviser recalls finding him engrossed in battle plans, studying the `war book' with a look of wonderment on his face.

He is also Blair's envoy to Northern Ire- land, making countless trips in a bid to broker an end to the Drumcree stand-off. Dublin insisted initially on dealing directly with Blair's office, in the shape of Powell, during the most recent discussions.

Powell's involvement in Ireland first brought him into conflict with Mowlam who suspected rightly that she was being bypassed (there is talk, too, of 'sticky' relations with Mandelson). She later blamed him for much of the whispering campaign against her. Mowlam, in turn, is the source of Powell's rift with Dobson who, if the former health secretary's friends are to be believed, would like to show Powell how tough politics can really be. Physically. He is convinced Powell was championing Mowlam as Labour's candidate for London Mayor until the bitter end, destabilising an already ill- starred campaign.

Labour MPs paint Powell as a junior Machiavelli, promoting Mowlam while rubbishing her, seeking to make her Lon- don Mayor to get her out of the Cabinet. It is his involvement in the game of who- gets-what job that causes so much discon- tent within Westminster Labour.

When members of the Cabinet stepped into Blair's room to hear their fate in the first reshuffle, they were surprised to find he was not alone. Sitting alongside the premier was Powell, the hidden hand as Blair hired and fired.

`He's the reason all our reshuffles have been messed up,' says a minister. 'He's not got a feel for politics but he's got this polit- ical role. Powell is one of the unelected gang that Blair has surrounded himself with. They are out of touch with the party.'

Powell is careful not to clash with Gor- don Brown, but many other ministers dread his 'the Prime Minister wants' phone calls, suspecting the PM may not want it but feeling helpless to challenge his chief of staff.

Powell's position might have been yet more insidious if Sir Robin Butler, when Cabinet Secretary, had not put his foot down and told Blair that he could not appoint him as his principal private secre- tary. In some respects it was a hollow vic- tory and Sir Robin's successor, Sir Richard Wilson, is no more enamoured of his existing role.

Powell is not the first in the family to serve a prime minister. His eldest broth- er, Sir Charles Powell (Jonathan pro- nounces it the usual Pow-ell', Charles `Pole), played a similar role for seven years as Lady Thatcher's foreign affairs private secretary. Yet he is closer social- ly as well as politically to his second eldest brother, Christopher, head of the BMP advertising group who was asked by Peter Mandelson to chair Labour's shad- ow communications agency. A fourth brother, Roderick, a wealthy computer executive, lives in America.

Rather than this strange hybrid, Jonathan Powell could have been a mandarin of the old school. The son of an air vice-marshal, he followed Charles to King's School, Canterbury, before reading modern history at University College, Oxford. After a master's degree at Pennsylvania University, he flirted with the media, joining the BBC before briefly joining Granada TV. Then in 1979 he was again coat-tailing Charles, entering the diplomatic service.

His rise was steady rather than spectac- ular but by 1991 he held the coveted First Secretary post in Washington where he was to establish links with the Clinton camp, recognising early on that George Bush would lose. There, too, he devel- oped his interest in Northern Ireland, complaining when Gerry Adams was first granted a US visa. Powell organised Blair's itinerary in January 1993 when the then shadow home secretary flew to Washington to learn the lessons of Clinton's campaign. Blair was impressed by the thirty-something diplo- mat; the official was impressed by He joined the Labour party the following month. When Blair became Labour leader the following year, he invited Powell to be his chief of staff. Powell agreed enthusiastically, declaring he was a 'lifelong supporter' of the Labour cause. Sir Charles was heard to mutter: `Well, it's news to me.'

Powell's marriage to his American-born wife Karen, a poet with whom he has two teenage sons, was dissolved in 1997. He met new partner Sarah Helm, a former European correspondent of the Indepen- dent newspaper, during regular trips to Brussels. The couple have two daughters, Jessica, two, and Rosamund Ysolda, who recently had her first birthday. Rosamund's arrival was announced in the Times, and in true Blairite fashion the couple were to prove there is a Third Way even in babysitting.

Rather than deciding which parent should stay at home to rock the cradle after a table was booked at Soho's Grou- cho Club media den, the pair checked in eight-week-old Rosamund with their coats. Not that the attendant objected. It made a change to umbrellas and she need- ed the cash. 'The girl in the cloakroom only works here because she can't get enough money as a child play specialist in the NHS,' the Downing Street aide was overheard explaining to companions. The moonlighting woman, who worked at Whitechapel's Royal London Hospital, must have hoped for at least the £3.60 an hour minimum wage for her babysitting. When the couple picked up their coats and the child, they realised they had no cash. A 'cheque in the post' was promised though we do not know whether or not it appeared, since the girl was gagged by her employers. Powell was furious when the baby story appeared in the press and will be squirming in the current spotlight, aware that in his post virtually all pub- licity is bad publicity.

It is doubtful whether the Mowlam–Dobson controversy will revive the 'second thoughts' Blair had about Powell's appointment shortly before the May 1997 election. But some at the heart of the government are convinced that, if he left, Powell would not be replaced.

Previous page

Previous page