SPAIN'S FINEST CAVA

Life of Bryan

Raymond Keene

ONCE THE WORLD CHAMPIONSHIP was decided, after game 20, Kasparov and Short continued to entertain the public at the Savoy Theatre (as well as a substantial television audience) with speed games, blitz games and three games with set themed openings. The themed openings harked back to the gambit tournaments of the early 20th century, or the match between Lasker and Tchigorin, designed solely to test the Rice Variation, an obscure and dubious line in the King's Gambit.

Both colours and openings were drawn by lot. In game one Kasparov was obliged to play an Evans Gambit, but after the set moves 1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bc4 Bc5 4 b4 Bxb4 5 c3 Nigel, to whom free will was returned at this stage, elected to go for the safe modern variation 5 . . Be7 6 d4 Na5, abandoning his extra pawn, in order to complete his development. For game two, Kasparov was Black and predestination insisted on the moves 1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Nf3 Be7 4 Bc4 Bh4+ . This, like game one, ended in a draw after a tough struggle.

Imagine my surprise, though, on open- ing last weekend's Sunday Times colour supplement, to discover that Martin Amis, writing an appreciation of his former friend Mark Boxer, had actually commented on this variation: 'Our friendship solidified over the chessboard. When playing White he typically favoured the King's Gambit. After 1 e4 e5, White offers the pawn sacrifice with 2 f4. The idea is to castle early and make dashing attacks down the cleared king's bishop's file. This opening is now discredited (so far as I can see White has no hope of castling after 3. . . Be7) but Mark had many racy successes with it.' .

Try telling this to Kasparov! He was not at all happy with his predetermined moves and was even less happy with his opening lot in the following game. Short — Kasparov: Theme Game 3, Savoy Theatre; King's Bishop's Gambit, Bryan Varia- tion.

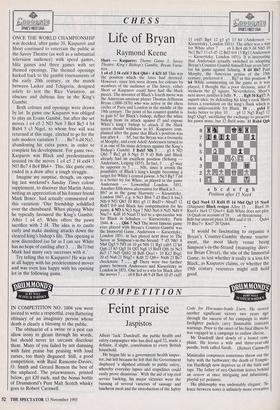

1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 8c4 Qh4+ 4 Kfl b5 This was 'the position which the fates had decreed. However, since lots were drawn for colours by members of the audience at The Savoy, either Short or Kasparov could have had the black pieces. The inventor of Black's fourth move was the American amateur player Thomas Jefferson Bryan (1800-1870) who was active in the chess circles of Paris and London in the middle of the 19th century. The point of his counter-gambit is to gain b7 for Black's bishop, deflect the white bishop from its attack against 17 and expose White's king's bishop to attack if the black queen should withdraw to hS. Kasparov com- plained after the game that Black's position was lost after 4. . . b5, but the Bryan was a favourite of Morphy, and even Adolf Anderssen turned to it as one of his main defences against the King's Bishop's Gambit. 5 Bxb5 Nf6 5 . . . g5 6 Nf3 Qh5 7 Be2 g4 8 Ngl f5 9 d3 8d6 and Black already had an excellent position (Schurig — Anderssen, Leipzig 1855). In fact, 5 . . . g5 may be superior to 5 . . . Nf6, since it avoids the possibility of Black's king's knight becoming a target for White's central pawns. 6 Nc3 Bg7 7 d4 is a better try for White, as played in the game Anderssen — Lowenthal London, 1851. Another fifth move alternative for Black is 5. . . Bb7 as in the game Harrwitz — Kieseritzky, London 1847, e.g. 6 Nc3 Bb4 7 d3 Bxc3 8 bxc3 Nf6 9 Nf3 Qh5 10 Rbl g5 11 Bxd7+ Nbxd7 12 Rxb7 0-0 and Black has compensation for his pawn. 6 Nf3 6 Nc3 Ng4 7 Nh3 Nc6 8 Nd5 Nd4 9 Nxc7+ Kd8 10 Nxa8 f3 led to a spectacular win for Black in Schulten — Kierseritzky, Paris 1844. 6. . . Qh6 7 Nc3 The most famous game ever played with Bryan's Counter-Gambit was the Immortal Game, Anderssen — Kieseritzky, London 1851, in fact played next door to The Savoy at Simpson's-in-the-Strand: 7 d3 Nh5 8 Nh4 0g5 9 Nf5 c6 10 g4 Nf6 11 Rgl cxb5 12 h4 Qg6 13 h5 Qg5 14 013 Ng8 15 Bxf4 0f6 16 Nc3 Bc5 17 NdS Qxb2 18 Bd6 Qxal+ 19 Ke2 Bxgl 20 e5 Na6 21 Nxg7+ Kd8 22 Qf6+ Nxf6 23 Be7 checkmate. 7 . . . g5 There were two further games between Anderssen and Kieseritzky in London in 1851. One led to a win for Black after the moves 7. . . c6 8 Bc4 d6 9 d4 Be6 10 d5 cxd5 11 exd5 Bg4 12 g3 g5 13 h4 (Anderssen Kieseritzky, London 1851). The other was a win for White after 7 . . c6 8 Bc4 d6 9 d4 Nh5 10 Ne2 Be7 11 e5 d5 12 Bd3 0-0 13 Rgl (Anderssen — Kieseritzky, London 1851). It is interesting that Anderssen actually switched to adopting Bryan's Counter-Gambit himself four years later for his game against Schurig. 8 d4 Bh7 Paul Morphy, the American genius of the 19th century, preferred 8 . . Bg7 in this position. 9 h4 While commenting on the game as it was played, I thought this a poor decision, since It weakens the g3 square. Nevertheless, Short's next move justifies it fully. 9. . . Rg8 10 Kgl!! A superb idea; by defending his king's rook Short forces a resolution on the king's flank which is most unfavourable for Black. 10 . . . gx114 It looks better to play 10 . . g4 11 Ng5 Rxg5 12 locg5 Qxg5, sacnficing the exchange to preserve his pawn mass, but 12 Bxf4 wins. 11 Rxh4 Qg6 a bc de f gh Position after 15 Nxe4 12 Qe2 Nxe4 13 Rxf4 f5 14 Nh4 Qg3 IS Nxe4

(Diagram) Black resigns After 15 . Bxe4 16 lbce4+ fxe4 17 Qxe4+ Kd8 White does not play

18 Oxa8 on account of 18. . . c6 threatening. . • Bd6 but instead plays 18 Bf4 and if 18. . . Oxh4 19 Bxc7+ Kxc7 20 Qxh4.

It would be fascinating to organise a Bryan's Counter-Gambit theme tourna- ment, the most likely venue being Simpson's-in-the-Strand (managing direc- tor Brian Clivaz), the site of the Immortal Game, to test whether it really is a loss for Black, as Kasparov claims, or whether the 19th century resources might still hold good.

Previous page

Previous page