Finland: Working and Waiting

By RICHARD BAILEY OF all the countries drawn into the game of sixes and sevens, the Finns have had the Worst luck. Back in 1955 they joined the Nordic Council, the organisation for co-ordinating poll- ° ,.eat and cultural activities in Scandinavia. Soon afterwards a move was started for a Nordic Customs Union, which would have set up a free trade area of the three Scandinavian coun- 11:10s, plus Finland, Iceland and Greenland. The rInns saw this as a nicely designed back-door nikto the European organisations from which neutrality pact with the USSR kept them °Lut. At the end of 1958, just as it looked as though a Nordic Customs Union agreement was nssible, the Free Trade Area negotiations broke ti0\"111 and the Scandinavian countries, led by wedeni hurried into the EFTA, leaving Finland neutral and neglected. „The next piece of bad luck was Mr. Mac- hlIan's announcement of his intention to iegntiate Britain's membership of the European e°nomic Community. This came just four ,10nths after Finland had at last succeeded in Deeoming an associate member of the EFTA; agreement as the first tariff changes under the EFTA took effect only at the beginning of i JIY, the Finns had every reason to feel. an- he rug that their neighbours had twice jerked , rug from under their feet. here is little that the Finns can do about it. n'leY have to preserve a neutral position, inac- cordance with the agreement made with the USSR the in 1947—the agreement that has kept ,silliand out of the OEEC and other European \"‘r,ganisations, and has compelled her to consult :111 the Soviets on any proposed ties with the exe S t, making even the association with EFTA k treatelY complicated. The Finns also have to to in mind the dependence of their economy Wte forests. About 74 per cent. of Finland's ;Pohrts come from industries depending on bi6„ntiRest in one form or another. As Sweden is the interest competitor in this industry, it is of vital to the Finns that they should both be in the same tariff group—which was why they worked so hard to get a toehold in the EFTA.

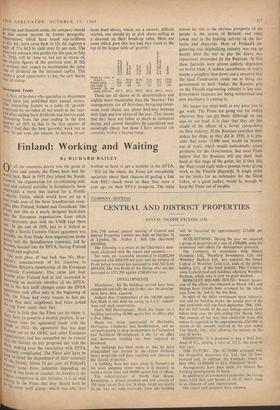

Yet on the whole the Finns are remarkably optimistic about their chances of getting a link with EEC—much more so than they were a year ago on their EFTA prospects. The main reason for this is the obvious prosperity of the people in the streets of Helsinki and other towns and in the bustling activity of the fac- tories and shipyards. Most of Finland's en- gineering and shipbuilding industry was run up hastily after the war to pay the heavy war reparations demanded by the Russians. At first these factories were almost entirely dependent on Soviet trade. A sudden cancellation of orders meant a complete shut-down and a situation that the local Communists could use to bring any government to heel. Today, the Russian grip on on the Finnish engineering industry is less sure. Everywhere factories are being modernised and new machinery is coming in.

No longer are ships built at any price just to get work. The Finns are going out for orders wherever they can get them. Although no one says so out loud, it is clear that they are less afraid of the effects of a Soviet clamp-down on their industry. If the Russians cancelled their orders for ships, as they did in 1958, it is pos- sible that some 15,000 men would be thrown 'out of work, which would undoubtedly create problems for the Government. But most Finns believe that the Russians will not show their hand at this stage of the game; for if they did, the West could reply with a prompt order giving work to the Finnish shipyards. A single order on the books for an icebreaker for the Great Lakes, or a giant tanker, would be enough to keep the Finns out of trouble.

Previous page

Previous page