Political Commentary

Governmental stutterings

Patrick Cosgrave

When so judicious an observer as Mr David Wood declares roundly that the Government's decision to spend E15 million to subsidise mortgage rates " will Probably prove to have done Mr Heath and the Cabinet more damage with their backbenchers than all the policy recantations and U-turns of the past two years Pat together," it is time to sit up and take deeper notice than hitherto of what is, after all, no more than a triviality in the whole range of governmental policies and problems today. Certainly it is true Mat trivial matters — the Profumo affair Was a case in point, and Hugh Dalton's and Mr Maudling's indiscretions are Others — often seem to have wholly disproportionate effects on the fortunes of administrations and, individuals. This iS, I think, not because of the nature of the triviality itself, but because of the contradictions and the loss of grip which It may reveal. When Mr Powell warned the Prime Minister recently that a government which wholly reversed the Principles on which it was elected — he Was thinking of the incomes policy — Ultimately destroyed itself, he was wrong. A total reversal is perfectly possible, if the new doctrines can be embraced with the same fervour as the old: the danger arises when a Prime Minister is trying to straddle two different philosophies at the same time. Then he is in severe danger of a hernia; his grip on affairs starts to loosen; and he stumbles into smaller contradictions which increasingly, reveal the existence of their larger fellows.

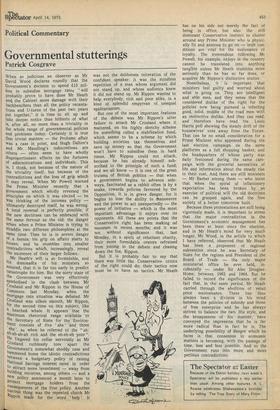

, Mr Heath's will is so formidable, and his dominarke of his ministers so assured, that it is far too early to predict catastrophe for him. But the sorry state of the Government was very effectively sYmbolised in the clash between Mr Crosland and Mr Rippon in the House of Commons last Monday, when the Mortgage rate situation was debated. Mr Crosland was silken smooth, Mr Rippon, for the second time on this subject, like a beached whale. It appears that the maximum rhetorical range available to the Secretary of State for the Environ!tient consists of five ahs ' and three ehs as when he referred to the " ahah-ah-ah-ah rich and the eh-eh-eh poor ". ie fingered his collar nervously as Mr Crosland ruthlessly tore apart the Government's somewhat shoddy case and t,tammered home the idiotic contradictions _betvveen a budgetary policy of raising I■lational Savings interest rates in order .attract more investment — away from building societies, among others — and a new policy announced a month later to Protect mortgage holders from the consequences of the first policy. Another curious thing was the repeated clutch Mr RiPpon made for the word ' help '. It was not the deliberate reiteration of the confident speaker: it was the mindless repetition of a man whose argument did not stand up, and whose audience knew it did not stand up. Mr Rippon wanted to help everybody, rich and poor alike, in a kind of splendid empyrean of unequal egalitarianism. But one of the most important features of the debate was Mr Rippon's utter failure to attack Mr Crosland where it mattered, on his highly sketchy scheme for somet'hing called a stabilisation fund, which seems to be a scheme by which building societies tax themselves and save up money so that the Government won't have to subsidise them in hard times. Mr Rippon could not attack, because he has already himself subscribed to the principle of such a fund; and we all know — it is one of the great truisms of British politics — that when a government begins to advance sideways, fascinated as a rabbit often is by a snake, towards policies favoured by the Opposition, it is in grave danger, for it begins to lose the ability to Manoeuvre and the power to act unexpectedly — the power of initiative — which is the most important advantage it enjoys over its opponents. All these are points that the Conservative right has been making ad nauseam in recent months; and it was not without significance that, last Monday, in a spirit of reluctant charity, their more formidable orators refrained from joining in the debate and chasing down the fox, Rippon.

But it is probably fair to say that there was little the Conservative critics of the right could do: their tactics now, must be to have no tactics. Mr Heath has on his side not merely t'he fact of being in office, but also the still dominant Conservative instinct to cluster around any Prime Minister who is physically fit and anxious to go on — both con ditions are vital for the sustenance of loyalty. The tremendous following Mr Powell, for example, enjoys in the country cannot be translated into anything tangible unless Mr Heath stumbles more seriously than he has so far done, or acquires Mr Rippon's distinctive stutter.

Nonetheless, it is important that ministers feel guilty and worried about what is going on. They are intelligent and able men, and they sense that the considered dislike of the right for the policies now being pursued is infecting good, solid, middle of the road men with an instinctive dislike. And they can read; and therefore have read the Louis Harris poll showing t'he steady drift of the housewives' vote away from the Tories.

That can be no small consideration for a Prime Minister who appeared during the last election campaign on the same platforms as a full shopping basket; and the headquarters of whose party was daily festooned during the same cam paign with the grocerial necessities of life and information about the steady rise in their cost. And there are still ministers — Mr Barber among them — who insist that when the spiral of inflationary expectation has been broken by an exercise of political will the old doctrines can be grasped again, and the free society of a better tomorrow built.

Because these protestations are still being vigorously made, it is important to stress that the major contradiction in the Government's economic management has been there at least since the election, and in Mr Heath's mind for very much longer. Mr Wood, in the article to which I have referred, observed that Mr Heath has been a proponent of regional subvention since he was Secretary of State for the regions and President of the Board of Trade — the only major ministerial office he ever held, incidentally — under Sir Alec Douglas Home, between 1963 and 1964. But he failed to record the significance of the fact that, in the same period, Mr Heath carried through the abolition of retail price maintenance. There has thus always been a division in his mind between the policies of subsidy and those of free enterprise and he has always striven to balance the two. His style, and the brusqueness of his manner, have conveyed the impression that he is far more radical t'han in fact he is. The underlying possibility of danger which he faces is that consensus in economic matters is becoming, with the passage of time, less and less possible. And so the Government runs into more and more perilous contradictions.

Previous page

Previous page