MY GHOST ESTATE

Communist rule has devastated the country houses of Poland.

Radek Sikorski intends to rebuild one

Dwor Chobielin, Poland

I'M not sure to what an expatriate English- man dreams of returning after years abroad. An old rectory in the home coun- ties? A flat in a Georgian terrace in Brighton? A semi-detached in Surbiton? When a Pole longs for arcadia he sees himself as the proud resident of a dwor or dworek: a (little) manor house. A classic dworek is 18th- or early 19th-century, ne6classical, and falls halfway between an aristocratic palace and a prosperous peasant house, with an obligatory white porch, pillars, a drive, and at least a hint of a park. It need not be grand — most used to be wooden — and in England it would qualify as little more than a spacious cott- age. Hundreds used to dot the length and breadth of Poland.

A dworek is not just a nice house to live in but the heart of our national myth. People who have not lived under occupa- tion perhaps cannot imagine the aura surrounding the places where national

aspirations were preserved. It was from their dworki that Polish nobles set off on their hopeless 19th-century insurrections and it was the dworki which were confis- cated as punishment after each failure. Besides, our collective imagination is only slowly admitting a Polish city style. (When Balzac wrote of Paris and Victorian En- glishmen lounged about in Pall Mall clubs our writers exalted the dworek.) We still dream of inhabiting one, of balls, hunting parties and, in the winter, kuligi — mad rides on snow-covered • country lanes in horse-drawn sleighs. In 'other words, living in a dworek is a calling as well as a pleasure.

What's become of most manor houses in Poland since the Communist takeover? One would have thought. that the new, superior society would cherish them. Marx dreamt of a future in which man — freed from alienation and drudgery — farms in the morning, fishes in the afternoon and, if the fancy takes him, writes an opera or a short story in the evening. He could have taken it lock, stock and barrel from a Polish 18th-century idyll about life in a dworek. From each according to his abili- ties — to each his kind of manor house. Ergo, one would have expected Commun- ists to preserve them, grant them as re- wards to heroes of socialist labour.

It didn't quite work out that way. Aris- tocratic palaces have on the whole fared relatively well; many have been preserved for show. The socialist state takes care of the nation's treasures. Party bosses adopted others for well-deserved holidays. But your average dworek, once the heart of every larger village, has virtually dis- appeared from the Polish landscape. I alternately cried and vainly banged my fist on the table looking through the photo- graphic register of the houses in my home county which have disappeared since the war. There was no campaign to level them, as in Russia. Just stupidity, fanaticism and sloth.

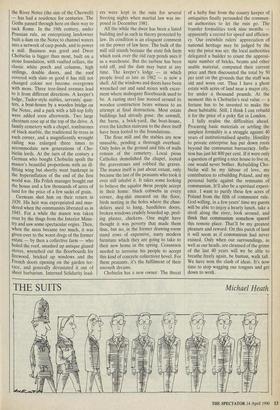

The fate of Chobielin, where I am writing this under a hole in the ceiling, is typical. The trunks of an ancient oak avenue suggest that the site — in the fold of the primaeval Vistula. valley, close by the River Notec (the size of the Cherwell) — has had a residence for centuries. The Goths passed through here on their way to sack Rome. In the 19th century, under Prussian rule, an enterprising landowner built a dam on the Notec to channel waters into a network of carp ponds, and to power a mill. Business was good and Dwor Chobielin is bigger than most, built on a stone foundation, with vaulted cellars, the classic white porch and columns, high ceilings, double doors, and the roof covered with slate so good it has still not changed colour nor become overgrown with moss. Three tree-lined avenues lead to it from different directions. A keeper's lodge, Tudor-style stables, servants' quar- ters, a boat-house by a wooden bridge on the Notec, and a park with a hill-top folly were added soon afterwards. Two large chestnuts rose up at the top of the drive. A family cemetery with a chapel, tombstones of black marble, the traditional fir-trees in each corner, and a magnificently wrought railing was enlarged three times to accommodate new generations of Cho- bielin lords. At the turn of the century a German who bought Chobielin spoilt the manor's beautiful proportions with an ill- fitting wing but shortly went bankrupt in the hyperinflation of the end of the first world war. His Polish manager bought out the house and a few thousands of acres of land for the price of a few sacks of grain.

Germans shot him on their return in 1939. His heir was expropriated and mur- dered when the communists liberated us in 1945. For a while the manor was taken over by the thugs from the Interior Minis- try and saw some spectacular orgies. Then, when the mess became too much, it was given over to the worst dregs of the former estate — by then a collective farm — who holed the roof, smashed up antique glazed stoves, wrenched out the floorboards for firewood, bricked up windows and the French doors opening on the garden ter- race, and generally devastated it out of sheet barbarism. Interned Solidarity lead- ers were kept in the ruin for several freezing nights when martial law was im- posed in December 1981.

All the while the dwor has been a listed building and as such in theory protected by law. Its condition is an eloquent comment on the power of law here. The bulk of the mill still stands because the state fish farm which took over the old carp ponds uses it as a warehouse. But the turbine has been sold off, and the dam may burst at any time. The keeper's lodge — in which people lived as late as 1982 — is now a shell. All the windows and doors have been wrenched out and sand mixes with excre- ment where mahogany floorboards used to be. A rusting steel line noosed around its wooden construction bears witness to an attempt at final destruction. Most estate buildings had already gone; the sawmill, the barns, a brick-yard, the boat-house, even the kitchen staircase to the dwor itself have been looted to the foundations.

The flour mill and the stables are now unusable, pending a thorough overhaul. Only holes in the ground and bits of walls remain of the cemetery. Local pious Catholics demolished the chapel, looted the gravestones and robbed the graves. The manor itself is just about extant, only because the last of the peasants who took it over still inhabit it. It takes some looking to believe the squalor these people accept in their home: black cobwebs in every corner, dog-shit smeared on the floor, birds nesting in the holes where the chan- deliers used to hang, handleless doors, broken windows crudely boarded up, peel- ing plaster, chickens. One might have thought it was poverty that made them thus, but no, in the former drawing-room stand rows of expensive, nasty modern furniture which they are going to take to their new home in the spring. Ceausescu needed to terrorise his people to accept this kind of concrete collectivist hovel. For these peasants, it's the fulfilment of their uncouth dreams.

Chobielin has a new owner. The threat of a hefty fine from the county keeper of antiquities finally persuaded the commun- ist authorities to let the ruin go. The transfer formalities took nine months apparently a record for speed and efficien- cy. Our erstwhile rulers' appreciation of national heritage may be judged by the way the price was set: the local authorities delegated a builder to count the approxi- mate number of bricks, beams and other usable material, computed their current price and then discounted the total by 50 per cent on the grounds that the stuff was old and worn out. Thus I have a ghost estate with acres of land near a major city, for under a thousand pounds. At the moment this is Chobielin's real value — a fortune has to be invested to make the dwor habitable. Still, I think I can rebuild it for the price of a poky flat in London.

I fully realise the difficulties ahead. Procuring basic materials or settling the simplest formality is a struggle against 40 years of institutionalised apathy. Hostility to private enterprise has put down roots beyond the communist bureacracy. Infla- tion has just hit 800 per cent. If it were only a question of getting a nice house to live in, one would never bother. Rebuilding Cho- bielin will be my labour of love, my contribution to rebuilding Poland, and my personal battle against the remnants of communism. It'll also be a spiritual experi- ence. I want to purify these few acres of Poland from the filth of communist rule. God willing, in a few years' time my guests will be able to enjoy a hearty lunch, take a stroll along the river, look around, and think that communism somehow spared this remote place. That'll be my greatest pleasure and reward. On this patch of land it will seem as if communism had never existed. Only when our surroundings, as well as our heads, are cleansed of the grime of the last 40 years will we be able to breathe freely again, be human, walk tall. We have won the clash of ideas. It's now time to stop wagging our tongues and get down to work.

Previous page

Previous page