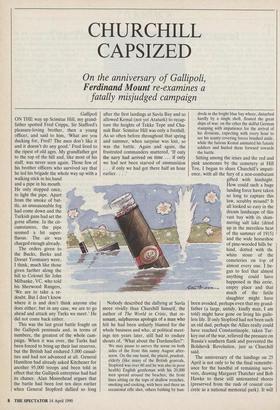

CHURCHILL CAPSIZED

On the anniversary of Gallipoli,

Ferdinand Mount re-examines a

fatally misjudged campaign

This was the last great battle fought on the Gallipoli peninsula and, in terms of numbers, the greatest of the whole cam- paign. When it was over, the Turks had been forced to bring up their last reserves, but the British had endured 5,000 casual- ties and had not advanced at all. General Hamilton had already asked Kitchener for another 95,000 troops and been told in effect that the Gallipoli enterprise had had its chance. Alan Moorehead argues that the battle had been lost ten days earlier when General Stopford dallied so long

after the first landings at Suvla Bay and so allowed Kemal (not yet Ataturk) to recap- ture the heights of Tekke Tepe and Chu- nuk Bair. Scimitar Hill was only a foothill. As so often before throughout that spring and summer, when surprise was lost, so was the battle. Again and again, the frustrated commanders muttered, 'If only the navy had arrived on time ... if only we had not been starved of ammunition . . . if only we had got there half an hour earlier. . .

Nobody described the dallying at Suvla more vividly than Churchill himself, the author of The World in Crisis, that re- sonant, sulphurous apologia of a man who felt he had been unfairly blamed for the whole business and who, at political meet- ings ten years later, still had to endure shouts of, 'What about the Dardanelles?': We may pause to survey the scene on both sides of the front this sunny August after- noon. On the one hand, the placid, prudent, elderly (like many of the British generals, Stopford was over 60 and he was also in poor health) English gentleman with his 20,000 men spread around the beaches, the front lines sitting on the tops of shallow trenches, smoking and cooking, with here and there an occasional rifle shot, others bathing by hun-

dreds in the bright blue bay where, disturbed hardly by a single shell, floated the great ships of war: on the other the skilful German stamping with impatience for the arrival of his divisions, expecting with every hour to see his scanty covering forces brushed aside, while the furious Kemal animated his fanatic soldiers and hurled them forward towards the battle.

The anniversary of the landings on 25 April is not only to be the final remembr- ance for the handful of remaining survi- vors, drawing Margaret Thatcher and Bob Hawke to these still untenanted shores (preserved from the rash of coastal con- crete as a national memorial park). It will also revive once again 'the terrible ifs', the alluring might-have-beens that Churchill so brilliantly deployed in the defence of his own seemingly shattered career.

After all, was there not something light- weight, unsustained, frivolous even, about the way the Gallipoli campaign was waged, not least in the diaries and letters — bobbish, lyrical, facetious by turns — of Sir Ian Hamilton with his enchanting smile and his twinkling eyes? An insect bite had prevented poor Rupert Brooke from get- ting any further than Skyros, but his friends and his prose style were as ubi- quitous as the insects. The natural beauty of the surroundings ennobled the stench of the trenches. 'It was a cobweb morning,' wrote Sergeant Hargrave of the 32nd Field Ambulance, recalling Stopford's Day of Rest, 'misty-thick, foretelling a steaming- hot day. Every sagebrush and wild thyme hassock festooned with spiders' webs heavy with dew.' Every one who fought there or merely visited seems to have been moved to write like John Masefield, in- cluding John Masefield. Classical allusions came up with the rations; the windy plains of Troy were only a few miles across the straits on the Asian side. Some of the French troops stationed at Cape Helles at the toe of the peninsula excavated anti- quities in their spare time, aided by the huge craters left by the shells of 'Asiatic Annie', the big Turkish gun across the water. Both Moorehead (1956) and Robert Rhodes James (1965) give marvellous de- scriptions of that strange heightened life a mixture of terror, boredom, dysentery and exhilaration which has made the whole tragic adventure ring in the memory to this day.

How peculiar it all was — peculiar, to start with, that we should be fighting the Turks at all, when, with only a fraction more diplomatic nous before the war, they might have been on our side (a fact which may explain the absence of rancour after the war and the mutual respect during it). And peculiar too for the Balliol subaltern sunning himself on these banks of asphodel to see only a few hundred yards away men in his own regiment under heavy fire in their trenches or clinging like seabirds to holes scrabbled in the cliff, often using corpses as sandbags or treading on their squashy faces. Peculiar too it must have been to return from the most vicious hand-to-hand fighting of the entire war biting, bayoneting, clubbing one's way a few yards forward only to be startled by pitiless enfilading fire and forced to scurry downhill again along the maze of gullies and on to the beach and splash into the sea to get away from the flies. Against the violent freshness of these contrasts, it is somehow all the more touching to read the same understated phrases in letters home as from any other British battlefield: 'We got fearfully cut up last night', 'it was most awfully disappointing for us at Anzac'. No wonder the Gallipoli campaign has pro-

duced two of the finest short histories of any campaign in British military history: Moorehead the better on the submarine battles in the Sea of Marmara and on the bizarre intrigues at Constantinople, Rhodes James the more intense, sharp and gripping on the actual fighting (though marred by a bitchy insistence on belittling Moorehead's research at every opportun- ity). Both manage superbly to balance the heroism against the horror, and to give just as full weight to the dash of the best commanders as to the lethargy of the worst.

There could be no accusations of sloth or lotus-eating at the middle of the three battlefronts, Anzac Cove. There, only a couple of miles down from Suvla, the jagged, sandy cliffs rear almost straight out of the sea. There is scarcely room for the little graveyard at the edge of the beach. This place — one of the most legendary in the history of warfare — is hardly a cove at all, no more than the faintest of indenta- tions in the roughest, least hospitable stretch of the coast. It is amazing that men could ever have fought their way to the top of the ridge, let alone held their trenches for months against the enemy above them. The ground is so cramped, so precipitous, so seamed with deceitful gullies and crevas- ses that any kind of coherent military advance seems inconceivable. Those cheerfully designated landmarks of the fiercest fighting — Plugge's Plateau, John- ston's Jolly — are mere pockets of scrub and scree, crammed to this day with the bones and equipment of those who died in them.

Yet all the fire and dash at Anzac Cove achieved little more than the lethargy and indecision at Suvla Bay. For all the reckless daring displayed at both, the Allied line never reached more than a mile or so inland, the great ridge which forms the spine of the peninsula was never control- led, the Turkish batteries were never si- lenced, and the Dardanelles were never forced. And when I gazed down towards Suvla from the top of the ridge, where Kemal had his headquarters, the ultimate failure of the Allies no longer seemed so surprising. What looked like a fairly easy stroll from below looked hellish, verging on impossible from above. Suppose the Bucks, Berks and Dorset Yeomanry had managed to capture the high ridge and fought their way on up the peninsula, might they not still, I wondered, have been intercepted by German reinforcements from the Gulf of Saros, or been cut to pieces by Turkish guerrillas in the cruel winter of the Thracian uplands (30 men froze to death in a single trench here in the last days before evacuation)? Constantino- ple still seemed a long way off, 200 miles and more, in fact.

What the Cassandras had said at the beginning turned out to be the case. After all, Churchill himself, before he was seduced by the marvels of modern artil- lery, had told the Cabinet in 1911 that the days of forcing the Dardanelles by warships were gone: 'Nobody would ex- pose a modern fleet to such peril.' And had not General Callwell, the Director of Military Operations, told Kitchener and Churchill the preceding autumn that, even with a force of 60,000 men, 'the attack is likely to prove an extremely difficult op- eration of war'? And had not Admiral Carden, the British commander in the Aegean, told Churchill that 'I do not consider the Dardanelles can be rushed. They might be forced by extended opera- tions with large numbers of ships'? Carden and Callwell both meant to discourage Churchill. They little knew their man. The First Lord telegraphed back, 'Our view is agreed by high authorities here' (principal- ly, it seems, the First Lord himself — he had not consulted the First Sea Lord, the 73-year-old Jacky Fisher, or anyone else who might turn out to be sceptical). 'Please telegraph in detail what you think could be done by extended operations.'

Churchill then used Carden's reply and the subsequent refinements of it to argue in The World in Crisis that 'I did not and I could not make the plan' and 'the genesis of this plan and its elaboration were purely naval and professional in their character'. Well, from this distance in time, it looks remarkably like a bouncing operation and a wilful misreading of a hesitant 'might' (which is what Carden later confirmed he intended) into a gung-ho can-do.

If Churchill had not been at the Admir- alty, it remains highly doubtful whether the Dardanelles plans would ever have been carried through on such a scale. There might have been a couple of naval born- bardments of the Straits, no doubt aban- doned when they turned out to be as costly as the 18 March assault which cost the navy three battleships. No doubt several British submarines would have slipped under the Turkish nets at the narrows and wreaked the same havoc in the Sea of Marmara as the incredible Lt-Commander Nasmith. There might have been one or two commando-style raids on the shore batter- ies. But would there have been landings involving half a million men, and would it all have gone on for nearly a year and cost 50,000 Allied lives?

As Mr John Terraine remarks, 'The peculiarity of the whole Gallipoli story is the number of times that the Allies came within inches of success; it is this, as much as anything, that make its memory so poignant . . . a series of "accidents" may be blamed for each successive failure. But can so many breakdowns, so similar in character, only be called "accidents"? Do they not seem to point to a chronic basic disorder?'

The most obvious weakness was the division of command. Even when General Hamilton and Admiral de Robeck were on speaking terms, they were often unable to get in touch with one another. And this misfortune was not merely a technical accident or the product of inter-service rivalry, it reached down to the very depths of the enterprise, which seemed unable to make up its mind whether it was to be primarily naval or military. To start with, the Straits were to be forced by the navy alone. Then the army was to silence the batteries first; then in the dying stages, when evacuation was virtually a certainty, Admiral Keyes hatched dramatic plans for the navy to blast its way through to Constantinople.

But why did the politicians never agree on a sufficiently large combined operation? Why was it always too little, too late? This is surely the crucial question, though it does not seem to have been asked much. The answer is that to have contemplated, openly and candidly, an operation of the necessary size would have drained the Dardanelles of most of their attractions as an alternative to the horrific slaughter of the Western Front. To call this thing by its right name, it would have been an invasion of Turkey — a country which had been only reluctantly dragged into the war by German arm-twisting and was much better left to doze on under the decrepitude of Ottoman rule. And any fool could see that an invasion might well tie up an Allied army of half a million men and more which is just what did happen later on in Salonica. Churchill himself wrote to Fisher in January 1915 that 'I would not grudge 100,000 men because of the great political effects in the Balkan peninsula but Ger- many is the foe, and it is bad war to seek cheaper victories and easier antagonists'.

Yet that is just what, with many hesita- tions and backtrackings, they were about to do. For all the cultivated sobriety with which the 40-year-old Churchill persuaded his older colleagues of the virtues of the scheme, there is no doubt that he — and most of them — saw the prospect as a with-one-bound-we-are-free operation, to be carried through at relatively modest cost against an inferior opponent. Only Hamil- ton, I think, had the grace to admit that he had found `Mehmetchik' a tougher nut than the Johnny Turk of British mytholo- gy. And there is no mistaking, either, Churchill's belief that success in the Dar- danelles would also carry him bobbing along on the crest of the wave.

`My God,' he said to Margot Asquith in January 1915, `this, this is living history. Everything we are doing and saying is thrilling — it will be read by a thousand generations, think of that! Why, I would not be out of this glorious, delicious war for anything the world could give me don't repeat that I said the word delicious, you know what I mean.'

Immediately after the Great War, it was this self-dramatising, self-regarding aspect of Churchill's character that struck people. He was seen as 'continually posing, almost strutting, for his portrait for posterity'. Dr Bean, the official Anzac historian, de- nounced Churchill's 'excess of imagina- tion', his layman's ignorance of artillery and the fatal power of a young enthusiasm to convince older and slower brains' (As- quith, Kitchener and Balfour were all in their mid-sixties). But under the heavy pounding of Churchill's own rhetoric and with the horror of Flanders burning ever deeper into the memory, by the 1930s the conventional wisdom had swung round to accept, more or less, Roger Keyes's claim that 'the forcing of the Dardanelles would have shortened the war by two years and spared literally millions of lives'. Liddell Hart described the policy as 'a sound and far-sighted conception, marred by a chain of errors in execution almost unrivalled even in British history'. Churchill's glo- rious achievements in the second world war gave this view a further lease of life. In the mid-1950s, Moorehead was still more inclined to blame the generals than the politicians.

'Fifteen years we've been commuting together on this train; 15 years all we've ever said is "Good morning" — I'd just like you to know, I love you.' But already the tide was turning against Churchill again, J. F. C. Fuller's consi- dered verdict in 1956 was that `Mr Chur- chill forced the Dardanelles card on the Government and the Government was incapable of playing the hand'. A. J. P. Taylor diagnosed the operation as an attempt to evade the basic problem that the Germans could be beaten only by a force of the equivalent size. Corelli Barnett surely gets through to the real point: `Surprise might have won an initial success, but sooner or later the German reserves would have arrived and the Allies would have faced a similar situation as in the West. As the second world war proved, Europe has no "soft underbelly".' The `Easterners' were just as much escapists as those who believed in a quick victory on the Western front. Since the American Civil War, large wars between well- matched opponents have not been decided without mass slaughter: in the Great War on the Western Front, in the second world war on the Eastern. That is the terrible truth which nobody wanted to face at the time and I don't think most people really want to face today since it involves accept- ing that the real donkeys were not the generals but the politicians and the public who insisted, on unconditional surrender. So much easier to blame silly old buffers in uniform.

In a way, the trouble with Churchill in 1915 was not success but poverty of im- agination. He had not at that stage (but then nor had anyone else) much instinctive understanding of the terrible imperatives of a people's war. His mind still bore traces of the dash and jingle of the low-cost victories of 19th-century colonial warfare. Of course, nobody was quicker than he to grasp what Raymond Aron dubbed 'the technical surprises' of modern wars; the fighting begins with cavalry and ends with tanks and aircraft. But did he as yet see how people's wars could mobilise entire populations and engender that inexhausti- ble determination to carry on to victory even in so apparently debilitated a nation as the Turks? After all, the only enduring legacy of Gallipoli — apart from the memory of so much carefree expenditure of heroism — was the forging of a popular will on the Turkish side which led ultimate- ly to Major Kemal becoming President Ataturk and the creation of modern fez- free Turkey. 'The key to Winston', Leo Amery remarked in 1929, 'is to realise that he is mid-Victorian and unable ever to get the modern point of view.' That defect became a grand virtue in 1940, when a certain lack of accommodation to moderni- ty was what was wanted. In 1915, by keeping alive the tempting illusion that somewhere, somehow there existed a short cut to victory, Churchill was making it possible for the same errors to be commit- ted on other Mediterranean shores in the next war.

In the end, it is hard not to agree with that erratic old firecracker, Jacky Fisher, who felt himself pursued by Churchill's quenchless advocacy like a man persecuted by a swarm of bees: 'You are just simply eaten up with the Dardanelles and cannot think of anything else. Damn the Dar- danelles! They will be our grave!' As the minibus bundled us back along the penin- sula to the long, weary road through the plains of Thrace, I began to feel the spell of the Dardanelles drop away and became once more convinced that the whole enter- prise had been not only a mistake but a mirage.

Previous page

Previous page