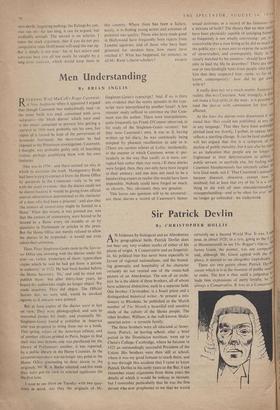

Sir Patrick Devlin

By CHRISTOPHER HOLLIS

AN Irishman by biological and an Aberdonian by geographical birth, Patrick Devlin does not bear any very evident marks of either of his places of origin. A Conservative and an Imperial- ist, his political bias has never been especially in favour of regional nationalisms, and the bound- ing generosity and hospitality of his character certainly do not remind one of the music-hall picture of an Aberdonian.. The son of an archi- tect, he is the eldest of three brothers, all of whom have achieved distinction, each in a separate field. One brother, Christopher, is a Jesuit priest and 'a distinguished. historical writer. At present a mis- sionary in RhOdesia, he published in the March number of The Month a beautifpl and sensitive study of the culture of the Shona people. The other brother, William, is the well-known Shake- spearian actor—a versatile family.

The three brothers were all educated at Stony- hurst. Patrick, -on leaving school, after 41 brief period in the Dominican novitiate, went up to Christ's College, Cambridge, where he became in 1925 an outstandingly successful President of the Union. His brothers were then still at school, where it was my good fortune to teach them, and it was through this accident that I came to know Patrick Devlin in his early years at the Bar. I can remember many arguments from those years the details of which it would be tedious to recount, but 1 remember particularly that he was the first person who ever prophesied to me that.we would certainly see a Second World Wai It was. I or pose, in about 1928; in a taxi, going to the 1.)11' at HamMersmith to see' The lieggar... Opera. Nif James Gunn, the painter. was our companito and, although Mr. Gunn agreed with the phecy, it seemed to me altogether improbable. , There are two points about Patrick Devial. career which it is at fhe moment of public Mb:I'', to make. The first is that. until a judgeship bade him expressions of party loyalty, he '‘.;, always .a Conservative. It was as Conservao` at a time when fashion there favoured a vague Liberalism, that he was elected President of the Cambridge Union. It is true that when Ramsay MacDonald appointed Sir William Jowitt, as he then was, Attorney-General in 1929, Devlin went into the office to assist him, but there was no sug- gestion that this was a political appointment. JOWitt indeed said, 'Frankly I would prefer a Labour man.' But young Socialist barristers were in those days few and far between. In 1945, when 1 was adopted as candidate for Devizes, I was delighted to find that Westwick, just outside Pewsey, where the Devlins lived, was in the con- stituency; and throughout that election campaign he was the outstanding speaker in my support. I remember an interminable summer evening of Socialist heckling that we had to endure together in the dreary little village of Ludgershall. After 1945 Conservative leaders wished him to come into the House to support them, and he could cer- tainly have had a safe seat had he wanted it. But he preferred the law.

The second point is this. There arc two sorts of successful judges—the pragmatic and the philo- sophical. There are good judges who are content merely to take the law as they find it and to ad- minister it competently. There are those whose minds are always restlessly inquiring into the origins, the philosophy and the justification of law. Devlin is par excellence a judge of the second sort. He published a distinguished little volume on Trial fly Jury. His last public appear- ance other than on the bench before his Nyasa- land appointment was to deliver last March under the chairmanship of Sir Maurice Bowra, the Maccabaean Lecture in Jurisprudence of the British Academy. The title of the lecture was 'The Enforcement of Morals,' and the question which it raised was how far the penal law should concern itself with the suppression of sin. This is not the Place either to summarise or to criticise his argu- ment. I merely want to show that he is a man above all concerned with the philosophy of law, and indeed we are told that one day--it may be not until after his retirement—we shall. receive What will no doubt be an important book in full statement of his philosophic opinions. Of his general standing as a judge, his work as President of the Restrictive Practices Court and the fre- quency with which his name was mentioned when the Lord Chief Justiceship was vacant bear testi- mony. Indeed, had not the Government held a Iji144*.opiOion. of his abilities they:would not have Ippointed him to head the Commission. W.,hataer criticisms may ber.trinde,:of the fi:satand Report, it would not be.piAsible to a,giiie anyone' more certain to think otiRlearly )itictly which were the questions whiel-rhe was Bed on to answer, or to distinguish. carefully )3aween what he certainly( knew and what he .:Sttroised. If the :Attorney-General cannot follow, II0e of the distinctions which he draws, it is by, means certain..that the fault lies with Mr. jqiitice Devlin. 'Sir, I have found you an argu- ,.tnent, but I'cannot find you '4n understanding.' ,'fiord Coleraine has —hitnelf made valuable Contributions to the .plliloaophy of politics, but Of all possible descriptions of Mr. Justice Dev- . Iths work I should have thought that 'intellec- tually dishonest' and 'naïve' were the most inapt.

Agree or disagree, here is a man intellectually honest to the verge of scrupulosity.

Previous page

Previous page