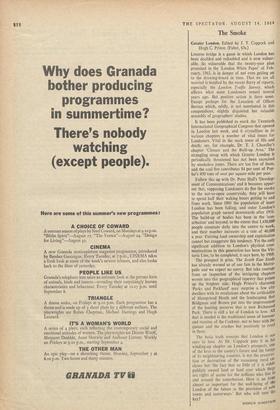

The Smoke

LONDON bridge is a game in which London has been doubled and redoubled and is now vulner- able. So vulnerable that the twenty-year plan promised in the 'London White Paper' of Feb- ruary, 1963, is in danger of not even getting on to the drawing-board in time. That we are all worried is testified by the recent flurry of reports, especially the London Traffic Survey, which affirms what most Londoners sensed several years ago. But positive action is there none. Except perhaps for the Location of Offices Bureau which, oddly, is not mentioned in this compendious, slightly disjointed but valuable assembly of geographers' studies.

It has been published to mark the Twentieth International Geographical Congress that opened in London last week, and it crystallises in its various chapters a number of vital issues for Londoners. Vital in the stark sense of life and death; see, for example, Dr. T. J. Chandler's chapter 'Climate and the Built-up Area.' The strangling smog with which Greater London is periodically threatened has not been exorcised by smokeless zones. There are too few of them, and the coal fire contributes 84 per cent of Pop- lar's 450 tons of soot per square mile per year.

Follow this up with Dr. Peter Hall's 'Develop- ment of Communications' and it becomes appar- ent that, supposing Londoners do flee the smoke to the not-so-open countryside, they will have to spend half their waking hours getting to and from work. Since 1901 the population of inner Loudon has been falling, and outer London's population graph turned downwards after 1951. The build-up of bodies has been in the 'con- urbation' and beyond, to the extent that 1,450,000 people commute daily into the centre to work, and their number increases at a rate of 40,000 a year. Existing land ownership and exploitation cannot but exaggerate this tendency. Yet the only significant addition to London's physical com- munications in this generation has been the Vic- toria Line, to be completed, it says here, by 1968.

The prospect is grim. The South East Study has already warned us of our fate in the Metro- polis and we expect no mercy. But take courage from an inspection of the intriguing chapters woven into this geographical tapestry that points up the brighter side. Hugh Prince's charming 'Parks and Parkland' may surprise a few citY dwellers with its revelations about the artificiality of Hampstead Heath and the landscaping that Bridgman and Brown put into the improvement of the hunting preserve that is now Richmond Park. There is still a lot of London to love. All that is needed is the traditional sense of humour and stamina of the Cockney, not to bear with the queues and the crushes but positively to revel in them.

The basic truth remains that London is not ours to love. As Dr. Coppock puts it in bis winding-up chapter on London's prospects, one of the keys to the county's future and the future of its neighbouring counties, is not the preserva- tion or destruction of the remaining rural en- claves but 'the fact -that so little of it is eithir publicly owned land or land over which thoe are rights of access for the millions who live in and around the conurbation. Here is an issoe almost as important for the well-being of tIlle London of the future as the provision of nelw towns and motorways.' But who will turn the key?

ANDREW ROBERTSON

Previous page

Previous page