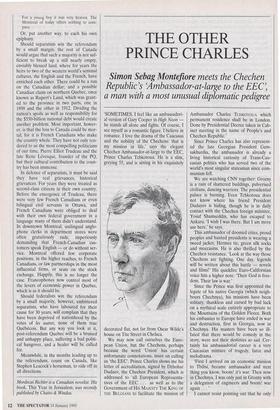

THE OTHER PRINCE CHARLES

Simon Sebag Montefiore meets the Chechen

Republic's 'Ambassador-at-large to the EEC', a man with a most unusual diplomatic pedigree

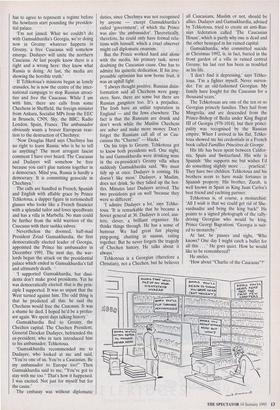

`SOMETIMES, I feel like an ambassadori- al version of Gary Cooper in High Noon he stands all alone and fights. Of course, I see myself as a romantic figure. I believe in romance. I love the drama of the Caucasus and the nobility of the Chechens: that is my mission in life,' says the elegant Chechen Ambassador-at-large to the EEC, Prince Charles Tchkotoua. He is a slim, greying 55, and is sitting in his exquisitely decorated flat, not far from Oscar Wilde's house on Tite Street in Chelsea.

We may now call ourselves the Euro- pean Union, but the Chechens, perhaps because the word 'Union' has certain unfortunate connotations, insist on calling us 'the EEC'. Prince Charles shows me his letter of accreditation, signed by Dzhohar Dudaev, the Chechen President, which is addressed to 'all European Representa- tives of the EEC . . . as well as to the Government of HIS MAJESTY THE KING OF THE BELGIANS to facilitate the mission of Ambassador Charles TCHKOTOUA which permanent residence shall be in London. Done by Presidential Decree taken in Cab- inet meeting in the name of People's and Chechen Republic.'

Since Prince Charles has also represent- ed the late Georgian President Gam- sakhurdia, the ambassador is already a living historical curiosity of Trans-Cau- casian politics who has served two of the world's most singular statesman since com- munism fell.

We are watching CNN together: Grozny is a ruin of shattered buildings, pulverised civilians, dancing warriors. The presidential palace is burning. Even Tchkotoua does not know where his friend President ,Dudayev is hiding, though he is in daily contact with the Chechen foreign minister, Yosuf Shamseddin, who has escaped to Ankara. 'I wish I was there. But I am more use here,' he says.

This ambassador of doomed cities, proud peoples and hunted presidents is wearing a tweed jacket, Hermes tie, green silk socks and moccasins. He is also thrilled by the Chechen resistance. 'Look at the way those Chechens are fighting. One day, legends will be written about this battle — novels and films!' His quickfire Euro-Californian voice hits a higher note: 'Their God is free- dom. Their law is war.'

Since the Prince was first appointed the legate of his native Georgia (which neigh- bours Chechnya), his missions have been solitary, thankless and cursed by bad luck on a mythical scale entirely appropriate to the Mountains of the Golden Fleece. Both his embassies to Europe have ended in war and destruction, first in Georgia, now in Chechnya. His masters have been so ill- fated that there would be comedy in the story, were not their destinies so sad. Cer- tainly his ambassadorial career is a very Caucasian mixture of tragedy, farce and melodrama.

`First I arrived on an economic mission to Tbilisi, became ambassador and next thing you know, boom! it's war. Then now in Chechnya, I was only just in Grozny with a delegation of engineers and boom! war again . . . '

I cannot resist pointing out that he only has to agree to represent a regime before the howitzers start pounding the presiden- tial palace.

`I'm not jinxed. What we couldn't do with Gamsakhurdia's Georgia, we're doing now in Grozny: whatever happens in Grozny, a free Caucasus will somehow emerge. Dudayev will unite the northern Caucasus. At last people know there is a right and a wrong here: they know what Russia is doing. At last, the media are showing the horrible truth.'

If Tchkotoua's missions began as lonely crusades, he is now the centre of the inter- national campaign to stop Russian atroci- ties and free the Caucasus. While I am with him, there are calls from some Chechens in Sheffield, the foreign minister from Ankara, Socialist MPs from the EEC in Brussels, CNN, Sky, the BBC, Radio London, Spain, France. The ambassador obviously wants a braver European reac- tion to the destruction of Chechnya: `Now Douglas Hurd says Chechnya has no right to leave Russia: who is he to tell us anything? The most arrogant fascist comment I have ever heard. The Caucasus and Dudayev will somehow be free because you can't glue nations together in a democracy. Mind you, Russia is hardly a democracy. It is committing genocide in Chechnya.'

The calls are handled in French, Spanish and English with affable grace by Prince Tchkotoua, a dapper figure in tortoiseshell glasses who looks like a French financier with a splendid tailor and loves speedboats and has a villa in Marbella. No man could be further from the wild warriors of the Caucasus with their sashka sabres.

Nevertheless the doomed, half-mad President Zviad Gamsakhurdia, the first democratically elected leader of Georgia, appointed the Prince his ambassador in December 1991. The next day, the war- lords began the attack on the presidential palace which ended in Gamsakhurdia's fall and ultimately death. '

`I supported Gamsakhurdia, but dissi- dents don't make good presidents. Yet he was democratically elected: that is the prin- ciple I supported. It was so unjust that the West turned against him. The odd thing is that he predicted all this: he said the Chechens would free the Caucasus. It was a shame he died. I hoped he'd be a profes- sor again. We spent days talking history.'

Gamsakhurdia fled to Grozny, the Chechen capital. The Chechen President, General Dzockar Dudayev, befriended the ex-president, who in turn introduced him to his ambassador, Tchkotoua.

`Gamsakhurdia recommended me to Dudayev, who looked at me and said, "You're one of us. You're a Caucasian. Be my ambassador to Europe too!" Then Gamsakhurdia said to me, "You've got to stay with me too." That's how it happened. I was excited. Not just for myself but for the cause.'

The embassy was without diplomatic duties, since Chechnya was not recognised by anyone — except Gamsakhurdia's exiled 'government', of which the Prince was also 'the ambassador'. Theoretically, therefore, he could only have formal rela- tions with himself, which a cruel observer might call diplomatic onanism.

But the Prince worked hard and alone with the media, his primary task, never doubting the Caucasian cause. One has to admire his quixotic dedication. If his irre- pressible optimism has now borne fruit, it was an uphill fight: `I always thought positive. Russian disin- formation said all Chechens were gang- sters. Sure, there are some but there are Russian *gangsters too. It's a prejudice. The Irish have an unfair reputation in England — and the Jews elsewhere. The fact is that the Russians are drunk and don't work while the Muslim Chechens are sober and make more money. Don't forget the Russians call all of us Cau- casians the "Churnei" — blacks.'

On his trips to Grozny, Tchkotoua got to know both presidents well. One night, he and Gamsakhurdia were drinking wine in the ex-president's Grozny villa when suddenly Gamsakhurdia said, 'We must tidy up at once. Dudayev is coming. He doesn't like mess.' Dudayev, a Muslim, does not drink. So they tidied up the bot- tles. Minutes later Dudayev arrived. The two presidents got on well 'because they were so different'.

`I admire Dudayev a lot,' says Tchko- toua. 'It is remarkable that he became a Soviet general at 36. Dudayev is cool, aus- tere, clever, a brilliant organiser. He thinks things through. He has a sense of humour. We had great fun playing ping-pong, chatting in saunas, eating together. But he never forgets the tragedy of Chechen history. He talks about it always.' Tchkotoua is a Georgian (therefore a Christian), not a Chechen, but he believes all Caucasians, Muslim or not, should be allies. Dudayev and Gamsakhurdia, advised by Tchkotoua, tried to create an anti-Rus- sian federation called `The Caucasian House', which is partly why one is dead and the other besieged in his ruined capital.

Gamsakhurdia, who committed suicide at Christmas 1992, is, in fact, buried in the front garden of a villa in ruined central Grozny; his last rest has been as troubled as his life.

`I don't find it depressing,' says Tchko- toua. 'I'm a fighter myself. Never surren- der. I'm an old-fashioned Georgian. My family have fought for the Caucasus for a thousand years.'

The Tchkotouas are one of the ten or so Georgian princely families. They hail from Mingrelia, and are descended from the Prince-Bishop of Bedia under King Bagrat III of Georgia (978-1014), but their princi- pality was recognised by the Russian empire. When I arrived in his flat, Tchko- toua showed me his credentials in a French book called Famillies Princieres de Georgie.

His life has been spent between Califor- nia, Spain and Switzerland. His wife is Spanish: `She supports me but wishes I'd do something slightly more . . . practical.' They have two children. Tchkotoua and his brothers seem to have made fortunes in Spanish property. His brother, Zurab, is well known in Spain as King Juan Carlos's best friend and yachting partner.

Tchkotoua is, of course, a monarchist: `All I wish is that we could get rid of She- vardnadze and bring the king back!' He points to a signed photograph of the rally- driving Georgian who would be king, Prince Georgi Bagrationi. 'Georgia is suit- ed to monarchy.'

At last, he pauses and sighs, 'Who knows? One day I might catch a bullet for all this . . . ' He goes quiet. How he would like to be remembered?

He smiles.

`How about "Charlie of the Caucasus"?'

Previous page

Previous page