List, list 0 list!

Gerald Jacobs SCHINDLER'S LEGACY: TRUE STORIES OF THE LAST SURVIVORS by Elinor J. Brecher Hodder & Stoughton, £14.99, pp. 496 Rs ipsa loquitur. This Latin tag, mean- ing 'the thing speaks for itself,' is applied by lawyers to clear-cut issues where no proof is required. It has a useful wider application, notably in literary matters. It certainly formed itself in my mind as I waded through this thick and glossy volume in which there is so much of value and so much that is dross.

I don't know if teachers of 'creative writ- ing' (of whom there seem to be ever- increasing thousands) convey to their students (of whom there seem to be increasing millions) the usefulness of res ipsa loquitur, but they certainly should. Where something genuinely does speak for itself, its communicative power derives pre- cisely from its pure, unalloyed state. Any attempt to underline or embellish it only reduces that power.

I don't know, either, if Miss Brecher has ever attended a creative writing class. She is American (as is the language in which her book is so relentlessly written), and thus quite likely to have done so, creative writing courses being a central feature of contemporary American culture. But she is also a journalist, and therefore quite unlikely to have done so.

In any event, she is strikingly reluctant to allow things to speak for themselves. And the particular things she has got her hands on don't just speak for themselves, they scream. For she has assembled the first- hand memories of around three dozen Schindleduden, the survivors of Oskar Schindler's now famous list, picked up in a painstaking round of interviews. If Spielberg's monumental film of Keneally's book was to have any spin-offs, they were never going to be of the T-shirt and soft-toy variety. Instead, the survivors themselves — now accorded celebrity sta- tus — have been prevailed upon to amplify the important message that we should never close our eyes to the fact that man is capable of the basest cruelty.

This message certainly can be found among the thousands of words compiled by Miss Brecher in a project that apparently

started life as a newspaper article about eight of the Schindletjuden in America.

Nobody, for example, can remain untouched by reading passages about babies and young children having their skulls smashed by the armed representa- tives of one of Earth's most civilised nations, or of a young man having to throw the freshly murdered corpse of his

grandmother into a mass grave, or the fol- lowing recollection, by Schindledude

Chaskel Schlesinger, of his neighbour, a dentist 'with two children and a beautiful wife:

He had the little boy in a backpack and had given him sleeping pills. He got him on the train, and the SS came in. This kid woke up, and the people were anxious that this boy should go out. They started pushing, and the little boy said, 'Don't push me; I know I'm going to die.' They took out the kid, and they pushed the father back in. They took out about thirty kids and took them a block away, and right away we heard the shooting.

By any standards, this is powerful stuff. So powerful, in fact, that the imagination can sometimes recoil from it. Unfortunate- ly, Miss Brecher too often feels compelled to wrap it up in layers of extraneous com- ment and superfluous biographical detail, laid on with thick, treacly prose.

This is a great pity. The sheer weight of material, with its repetitive horror and complex interrelationships between several of the Schindleduden, is hard enough to negotiate as it is, without our being told that the work of one man, who has become an artist, 'tweaks the senses with colours more vivid than nature's'. Or, of a mother who suffered the unbearable irony, after all she had endured in the War, of seeing her young daughter die from cancer in 1990, that she is a 'fortress of quiet control', and that 'diamonds couldn't bribe this murder- er' who took her daughter 'with the pitiless

amorality of a storm trooper'.

So, this is certainly not a book you can sit down and read from cover to cover. You have to work hard to obtain the material that it has to offer. But the effort will be repaid. This is material so substantial, so important in the face of racial and religious prejudice, of ignorance, of chic ethnic nationalism, of historical revisionism that seeks to diminish or deny the holocaust, that it needs to gain as wide a currency as possible.

If you pick your way through the author's clutter, you will find, in the original state- ments of the survivors, a number of enlightening observations about general concepts like faith, memory, survival, sani- ty, community and intermarriage, and about particular individuals. There are numerous testimonies to the wanton cruel- ty of the Plaszow commandant, Amon Goeth. And, indeed, to the deep human kindness of Oskar Schindler himself.

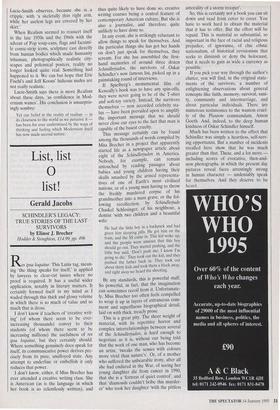

Much has been written to the effect that Schindler was simply a heartless, self-serv- ing opportunist. But a number of incidents recalled here show that he was much greater than that. These, and a lot more including scores of evocative, then-and- now photographs, in which the present day pictures reveal faces arrestingly strong in human character — undeniably speak for themselves. And they deserve to he heard.

Previous page

Previous page