Learning to speak sailing

Lucy Fleming charts her progress in the Capetown to Boston race

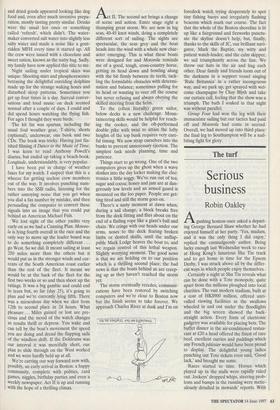

For an actor there's a rather worrying time when the final dress rehearsal is over and there's an hour or so to kill before you present the play to its first audience. There's not much to do except heed the director's last-minute notes, open some good-luck cards and panic. I felt in a simi- lar situation sitting on board the yacht Motorola, in a brisk wind, under the shad- ow of Table Mountain, waiting for the start of leg five of the BT Global Challenge from Capetown to Boston. The only prob- lem was: no dress rehearsal and not much in the way of a script.

The curtain rose as Table Mountain receded and we set off on our 40-day race. The boats had been blessed by Bishop Desmond Tutu with a charming prayer about going out to sea. It mentioned that the sea turned sailors into men who reeled and staggered; it seemed to me that some of them managed that on dry land. We cast off and gave three cheers for Capetown who waved furiously back. The start was incredibly fraught with spectator boats and foolhardy windsurfers weaving in and out of the fleet as we edged round buoys and jostled for places. These 67-foot steel yachts have a crew of 14 and take a little time to manoeuvre in crowds. With cries and yells and winches screaming, the 14 identical boats flexed their muscles, elbowed each other aside and pulled away towards Cape Cod some 7,000 miles ahead. With spinnakers flying, it struck me that they resembled a flock of pouter pigeons on the water.

I am not a sailor; but having done a little training I found myself scrambling about doing as I was told and learning about life aboard a racing yacht in no time at all. These boats are manned by crew 'volun- teers' who have paid for the chance to sail round the world, and each yacht has a skip- per and probably mate or qualified watch leaders. The yachts are built for toughness and are labour-intensive. Considering that they had just completed the incredibly tough 6,000 mile leg from Sydney to Capetown through the soulless and aggres- sive Southern oceans, they were in remark- ably good order. As indeed were the crews who were rightly proud of their achieve- ment but glad it was over.

We soon settled into our watch routine: six hours on and six off during the day and similarly four at night. My first impression was how relaxed and jolly it all was. This is probably because our skipper, Mark Lodge, is a very funny and laid-back man, con- stantly smiling, unless you've just woken him, full of wisdom and common sense. He had never sailed until he joined the previ- ous race as a crew volunteer. We were a varied cast with different backgrounds: an accountant, architect, teacher, micro-biolo- gist, doctor, wind-surf instructor, four girls and ten men, two Brazilians, one South African, one Australian, three Scots and the rest English. The core crew had become a strong working team who seemed able to turn their hands to anything: sewing sails, baking bread and scones, mastering the complexities of weather faxes, to say nothing of sailing.

Sailing. I was climbing a steep learning curve as I grasped at the complexities of vocabulary as well as technique. A new lan- guage appeared as I discovered lazy guys, flaking sheets, peeling, kickers, clews and leeches, not to mention dedicated winches. I feel confident that I can speak sailing now, and I'm still practising my running bowline.

Food started off very promisingly but things declined as the fresh food ran out and dried goods appeared looking like dog food and, even after much inventive prepa- ration, mostly tasting pretty similar. Drinks were the usual hot ones or something called 'refresh', which didn't. The water- maker converted salt water into slightly less salty water and made a noise like a gout- ridden MFH every time it started up. All the crew were issued with a chocolate and sweet ration, known as the nutty bag. Sadly, my family have now applied this title to me.

Night sailing under tropical skies was unique. Shooting stars and phosphorescence betraying the delightful outriding dolphins made up for the strange waking hours and disturbed sleep patterns. Sometimes you get up four times in a day. Surreal conver- sations and loud music on deck seemed normal after a couple of days. I could and did spend hours watching the flying fish. For ages I thought they were birds.

The kit list was spartan, including the usual foul weather gear, T-shirts, shorts (optional), underwear, one book and two CDs. The book was tricky. Having just fin- ished filming A Dance to the Music of Time, I was keen to read Anthony Powell's diaries, but ended up taking a beach-book. Longitude, understandably, is very popular.

I have been put in charge of weather faxes for my watch. I suspect that this is a wheeze for getting useless crew members out of the way. It involves punching num- bers into the SSB radio, listening for the rather annoying noise that you get when you dial a fax number by mistake, and then persuading the computer to convert these signals into an image that you could put behind an American Michael Fish.

We lost sight of the other yachts very early on as we had a Cunning Plan. Motoro- la is lying fourth overall in the race and the only way to move up the leader board was to do something completely different . . . go West. So we did. It meant sailing at least 250 miles more than the others but it would put us in the stronger winds and cur- rents of the South American coast earlier than the rest of the fleet. It meant we would be at the back of the fleet for the first two weeks or so and then shoot up the ratings. It was a big gamble and could end in tears but, so far (day 25), it's going to plan and we're currently lying fifth. There was a miraculous day when we shot from 12th to second place in 24 hours. What pleasure .. . Miles gained or lost are pre- cious and the mood of the watch changes as results thrill or depress. You wake and can tell by the boat's movement the speed you are doing and dread the flapping sails of the windless drift. If the Doldrums was our interval it was mercifully short, our plan to slide through on the West worked and we were hardly held up at all.

We're carving our way forward now with, possibly, an early arrival in Boston: a happy community, complete with politics, card games, niggles, birthday parties and even a weekly newspaper. Act II is up and running with the hope of a thrilling climax. Act II. The second act brings a change of scene and action. Enter stage right a thumping great storm. We are now in big seas, 40-45 knot winds, doing a completely different sort of sailing. The sights are spectacular, the seas grey and the boat heads into the wind with a whole new char- acter emerging. This is what these boats were designed for and Motorola reminds me of a good, tough, cross-country horse, getting its head down and bowling along with the bit firmly between its teeth, tack- ling the formidable obstacles with determi- nation and balance; sometimes pulling for its head or wanting to veer off the course but never refusing and always obeying the skilled steering from the helm.

To the (often literally) green sailor, below decks is a new challenge. Moun- taineering skills would be helpful for reach- ing the cooker, and the oft-performed double pike with twist to attain the lofty heights of the top bunk requires very care- ful timing. We now strap ourselves into the bunks to prevent unnecessary ejection. The simplest task needs planning, time and patience.

Things start to go wrong. One of the two computers gives up the ghost when a wave sloshes into the day locker making the elec- tronics a little soggy. We've run out of tea, sugar and cocoa; honey and jam are at dan- gerously low levels and an armed guard is mounted on the loo paper. People are get- ting tired and still the storm goes on. There's a nasty moment at dawn when, during a sail change, a block breaks free from the deck fitting and flies about on the end of a flailing rope like a giant's ball and chain. We cringe with our heads under our arms, noses to the deck fearing broken limbs or dented skulls, until the unflap- pable Mark Lodge heaves the boat to, and we regain control of this lethal weapon. Slightly worrying moment. The good news is that we are holding on to our position which is a thrilling second place; the bad news is that the boats behind us are creep- ing up as they haven't reached the storm yet. The storm eventually recedes, communi- cations have been restored by switching computers and we're close to Boston now but the finish seems to take forever. We approach Charles River at dusk and I'm on foredeck watch trying desperately to spot tiny fishing buoys and irregularly flashing beacons which mark our course. The fact that the whole of the Boston shoreline is lit up like a fairground and fireworks punctu- ate the skyline doesn't help, but, finally, thanks to the skills of JC, our brilliant navi- gator, Mark the Baptist, my witty and patient watch-leader, and the calm skipper, we sail triumphantly across the line. We throw our hats in the air and hug each other. Dear family and friends loom out of the darkness in a support vessel singing `Rule Britannia' in a rather incongruous way, and we park up, get sprayed with wel- come champagne by Chay Blyth and take our curtain call, feeling that the show was a triumph. The bath I soaked in that night was without parallel.

Group Four had won the leg with their immaculate sailing but our tactics had paid off and Motorola had come in second. Overall, we had moved up into third place: the final leg to Southampton will be a nail- biting fight for glory.

Previous page

Previous page