Political Commentary

Mr. Brown's Famous Last Words

By ALAN WATKINS

E are governed by words,' said Stanley Baldwin, and the events of the past week have certainly borne out the truth of his observa- tion. One sentence in Mr. George Brown's speech of last Thursday has raised a multitude of questions: about the nature of Mr. Harold Wil- son's leadership, about the future of the Govern- ment's programme and, not least, about Mr. Brown's position inside both the Cabinet and the parliamentary party. No doubt it is comforting to dismiss, as some Labour politicians have done, the remarkable happenings of the last seven days as a 'storm in a teacup' which will 'soon blow over.' It is comforting, but also more than a little disingenuous. For when the Labour party chair- man• crn.make a public appeal for dignity and restraint, when a special meeting of the Cabinet is summoned, when the Prime Minister decides to address his party at Westminster, when he further decides to change his plans for a party political broadcast—when all this happens there is clearly something more than a storm in a teacup (unless the teacups at Number 10 are quite• unusually large ones) and it is reasonable to assume that some powerful forces have been operating.

But before investigating the broader aspects of the affair we should try to piece together the known facts. As far as one can sec, the course of events was as follows. On Tuesday of last week Mr. Desmond Donnelly was touring an electrical factory at Croydon. He was told that a Mr. Clark wanted to speak to him on the telephone. Mr. Clark, as it turned out, was one of Mr. Brown's senior officials at the Department of Economic Affairs. He informed Mr. Donnelly that Mr. Brown would like to see him. This was not the first time that Mr. Brown had met Mr. Donnelly to talk about steel. They had seen each other on at least one previous occasion : but it seems that there was no series of meetings.

Thus on Wednesday afternoon Mr. Donnelly presented himself at the DEA and, after some talk with Mr. Brown, suggested that Mr. Wood- row Wyatt should join the party. Mr. Wyatt was summoned (though he might object to the word), and the three of them talked for several hours. At this stage, it appears from indirect evidence, Mr. Brown was not thinking primarily in terms of a verbal compromise. Instead he appealed to the two rebels' sense of party loyalty—and he also held out the carrot that, if they did indeed vote for the White Paper, it could well be that no Steel Bill would be forthcoming.

Mr. Donnelly and Mr. Wyatt, however, were not satisfied. Nor, it subsequently became plain,

was Mr. Brown. At around midday on the Thursday he sent a message to Mr. Donnelly telling him to forget everything he had said on the previous day. Mr. Donnelly contacted Mr.

Wyatt, who in turn got in touch with Mr. Brown. The latter two agreed to meet after Mr. Wyatt's speech in the Commons that evening. Mr. Wyatt's speech finished at 7.35. He then had a discussion with Mr. Brown outside the Chamber. Shortly

before Mr. Donnelly rose to speak, at 8.41, Mr.

Wyatt told him that he thought everything was going to be all right but that 'it would have to be cleared by Harold.' Sometime after the end of his sixteen-minute speech Mr. Donnelly was told by Mr. Wyatt that the Prime Minister had in fact agreed to what Mr. Brown was going to say.

The official version of events is that Mr. Wilson learnt of the formula only when he took his seat on the front bench at 9.20. Even then, it appears, he did not know the precise form of words: Mr. Brown offered to show him the typescript, which he loftily waved aside. And all this may well be and probably is true. But can it seriously he main- tained that tip till 9.20 on Thursday evening Mr.

Wilson was completely in the dark as to Mr.

Brown's activities? If so, then the Prime Minister ought surely to be having a close look at his own

intelligence service, of which he is normally very•

proud. But there is some reason for believing that the intelligence service did not let Mr. Wilson down and that Mr. George Wigg kept him in- formed of developments. Admittedly this is a long way from instigation; it is some way from tacit approval; but at the same time it is far re- moved from complete ignorance.

However this may be, there is no question that, from the Prime Minister's appearance on the front bench onwards, Mr. Brown and Mr. Wil- son were in this together—a fact which tended to be obscured in some accounts that appeared earlier this week. For at the end of the Com- mons speech Mr. Wilson took Mr. Brown by the hand and told him what clever fellows they both were. On Friday Mr. Wilson was just as enthusiastic. On Saturday Mr. Wilson approved the speech which Mr. Brown was to make at Swadlincote. Derbyshire, and which repeated the 'offer' to the steelmasters. Not only did M r. Wil- son approve the speech; more, he added a sen- tence of his own.

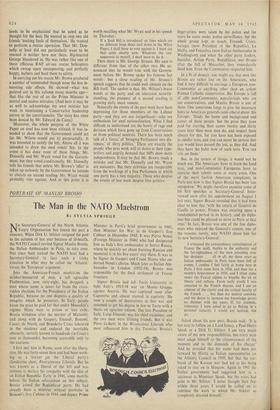

Mr. Brown bears a heavy responsibility, but it

needs to be emphasised that he acted as he thought for the best. He wanted to stop two old friends 'making fools of themselves.' He wanted to perform a rescue operation. That Mr. Don- nelly at least did not particularly want to be rescued is neither here nor there. Big-hearted George blundered in. He was rather like one of those officious RAF air-sea rescue helicopters which swoop upon unsuspecting, and perfectly happy, bathers and haul them to safety.

In carrying out his rescue Mr. Brown produced a number of unintended though none the less in- teresting side effects. He showed—what was pointed out in this column many months ago— that like -the rest of us the Prime Minister is mortal and makes mistakes. (And here it maybe as well to acknowledge my own mistake last week in mentioning a Conservative leadership survey in the constituencies. The story has since been denied by Mr. Edward du Cann.)

Moreover, the whole purpose of the White Paper on steel has now been vitiated. It was in- tended to show that the Government could act (as Mr. Wilson would put it) purposefully. It was intended to satisfy the left. Above all it was intended to draw the steel rebels' fire. In the event it has done none of these things. Mr. Donnelly and Mr. Wyatt voted for the Govern- ment, but they voted conditionally. Mr. Donnelly tells his friends that unless Mr. Brown's 'offer' is taken up seriously by the Government he intends to abstain on second reading. Mr. Wyatt would probably vote against. And at this point it is worth recalling what Mr. Wyatt said in his speech on Thursday : If a Steel Bill is introduced on lines which are no different from those laid down in the White Paper, I shall have to vote against it. 1 must say that quite clearly now. Whatever the con- sequences to myself, 1 shall have to do it.

Then there is Mr. George Strauss. His case is different from that of the other two. He an- nounced that he would vote with the Govern- ment before Mr. Brown spoke his famous last words: but a close reading of Mr. Strauss's speech suggests that he could well abstain on the Bill itself. The upshot is that, Mr. Wilson's brave words at the party and on television notwith- standing, the prospect of a second reading is growing daily more remote.

Naturally the events of the past week have been depressing for those members of the Labour party—and they are not insignificant--who are enthusiasts for steel nationalisation. What I find difficult to understand are the howls of rage and derision which have gone up from Conservatives or from political neutrals. There has been much talk of a 'farce,' of 'bringing Parliament into dis- repute,' of 'dirty politics.' These are exactly the people who next week will sit down at their type- writers and angrily demand that MPs show more independence. It may be that Mr. Brown made a mistake and that Mr. Donnelly and Mr. Wyatt are nuisances. But their activities are inseparable from the workings of a free Parliament in which one party has a tiny majority. Those who despise the events of last week despise free politics.

Previous page

Previous page