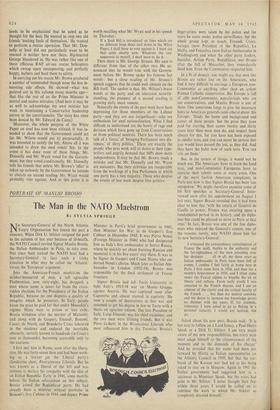

PORTRAIT OF MANLIO BROSIO

The Man in the NATO Maelstrom

By SYLVIA SPRIGGE

No Secretary-General of the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation has found the post a sinecure. When Dirk U. Stikker resigned the post' in the autumn of last year because of ill-health, the NATO Council invited Signor Manlio Brosio, the Italian Ambassador in Paris, to take over. Not since Suez rocked the NATO boat had a Secretary-General to face such a tricky situation in what may be called the 'Atlantic' versus the 'European' argument.

Into the American-French maelstrom the mildest-mannered of men, a tall agreeable Piedmontese, now sixty-eight, has dropped; a man whose name is never far from the crisis- ridden elections for the Presidency of the Italian Republic, because no one disputes a quality of integrity which he possesses. In Italy, people know the price he paid for that under Mussolini's regime. Many went to prison or into exile; Brosio withdrew after the murder of Matteotti, and along with de Gasperi, Einaudi, Bonomi, Casati, de Nicola and Benedetto Croce laboured in the shadows and endured the inevitable obscurity, secretly known to hundreds (in Croce's case to thousands), becoming accessible only to the cautious.

I first met him in Rome, soon after the libera- tion. He was forty-seven then and had been work- ing as a lawyer on the Liberal party's clandestine sheet, Risorgimento Liberate. But he was known as a liberal of the left and was anxious to declare his sympathy with the idea of an Italian Republic. Early in 1946, some months before the Italian referendum on this subject, Brosio joined the Republican party. He had already been a minister without portfolio in Bonomi's first Cabinet in 1944, and deputy Prime Minister in Parri's brief government in 1945, then Minister for War in de Gasperi's first Cabinet in December 1945. It was Pietro Nenni (Foreign Minister in 1946) who had designated him as Italy's first ambassador to Soviet Russia, where he quickly set about learning Russian and mastered it in his five years' stay there. It was to be Signor de Gasperi and Count Sforza who en- dorsed Nenni's choice. Much later as Italian Am- bassador in London (1952-54), Brosio was responsible for the final settlement of Trieste frontiers.

Signor Brosio had left Turin University to fight Italy's 1915-18 war on Monte Grappa against Austria. He was captured soon after Caporetto and almost starved in captivity. He won a couple of decorations in that war and returned to get his degree in law in Turin with a thesis on agrarian reform. The late President of Italy, Luigi Einaudi, was his chief examiner, and the two men were lifelong friends. But it was Piero Gobetti in the Rivoluzione Liberate who most influenced him in the Twenties. Brosio's finger-prints were taken by the police and for years he came under police surveillance, but the whole group kept in touch, Einaudi. Croce, Saragat (now President of the Republic), La Malfa, and Fenoaltea (now Italian Ambassador in Washington), and when the other party leaders, Socialist, Action Party, Republican, met Brosio after the fall of Mussolini, they immediately liked him. Even the Communists respected him.

In a fit of despair, one might say that men like Brosio are rather lost on the Americans. who find it very difficult to envisage a European non- Communist as anything other than an ardent Roman Catholic conservative. But Europe is full of able non-Communist, non-clericals who are not conservatives, and Manlio Brosio is one of them. One'sometimes longs to give the necessary hints to American generals (and others) about this Europe: 'Study the home and background and career of these people. See the price they have paid for starting their career twenty and thirty years later than most men do, and respect them always for this, for you have not been exposed to similar tests, and you can never be certain that you would have passed the test, as they did. And they have the habit now of such tests. You can rely on them.'

But, in the nature of things, it would not be much use. The Americans have to learn the hard way, and non-Communist Europeans have to exercise their talents anew at every crisis. One of the more foolish American complaints in Paris just now is that Signor Brosio has been 'too outspoken.' We might therefore examine some of his first speeches as Secretary-General. Inter- viewed soon after his appointment on August 1 last year, Signor Brosio revealed that it had been clear to him that 'with the return of General de Gaulle to power, France was entering upon a fundamental period in its history, and no diplo- mat but could be pleased to serve in Paris at that time.' In fact, Brosio was one of the few diplo- mats who enjoyed the General's esteem, one of the reasons, surely, why NATO chose him for its new Secretary-General: I witnessed the extraordinary consolidation of France [he said], thanks to the authority and the far-sightedness of the man presiding over her destinies . . . all in all, my three years as Italian ambassador in Paris have been full of events. I confess I feel fairly at home here in Paris. 1 first came here in 1924; and then for a month's honeymoon in 1936, and I often came under the Fascist rdgime to breathe the air of liberty and culture. From early youth I was attracted to the French theatre, and I am an admirer of the clarity and the critical faculty of the French . . . but then my natural curiosity and my desire to increase my knowledge grows no dimmer with the years. If, for example. tomorrow I were asked to go to Peking in a personal capacity. I would not hesitate, but

go. . .

Asked about his new post, Brosio said: 'It is not easy to follow on a Lord Ismay, a Paul-Henri Spaak or a Dirk U. Stikker. I am very much aware of my new responsibilities, but every man must adapt himself to the circumstances of the moment and to the demands of his charge.' And he revealed that his name had been put forward by Sforza as Italian representative on the Atlantic Council in 1950, but that the out- break of the Korean war had led to his being asked to stay on in Moscow. Again in 1961 the Italian government had suggested him as a successor to Monsieur Spaak, but the votes had gone to Mr. Stikker. '1 never thought then that within three years I would be called on to continue the work to which Mr. Stikker so completely devoted himself.'

Of his home life and hobbies (he still plays tennis) Brosio said he was one of six brothers and they were still a very united family. He used to play the national Piedmontese game of bowls but now his main occupations were reading aloud with his wife and walking. And there were family reunions with his brothers and nephews (he has no children) round his mother's hearth in Piedmont, for she, at ninety-one, still ruled the Brosio home in Turin.

And what of NATO itself? He clearly envisages the alliance as one of 'democratic governments, which must therefore be sustained by public opinion in the member states.' And is it?

A few months later, speaking at a banquet early this year, organised in his honour by the French Association for the Atlantic Community, a body one imagines somewhat in a minority in contemporary Paris, he pinpointed the 'atmo- sphere of well-being and indifference in the free world, which have, almost ipso facto,- been pro- duced thanks to the efforts and solidarity of our Alliance over the last fifteen years, and have given rise to a certain measure of doubt and confusion as to the path, which should be followed in the future. . . .' But he himself has no doubts at all about the continuing need for NATO. He is aware of the current dispute between 'European- ism' and 'Atlanticism,' but he does not feel they need clash. He sees the Atlantic alliance, in the last resort, as the guarantee of protection between Europe and North America, a reciprocal affair which, however, has so far owed far more to North America in the way of aid and defence than to Europe. But he maintains:

Europe has also made its contribution to the security of the United States, as has been demonstrated by the outstanding examples of solidarity over Cuba, when France and other allies of course immediately sided with the United States.

He knows that the argument goes on inside France as to whether de Gasperi, Schuman and Adenauer only conceived a united Europe as `being closely and permanently linked with the USA,' but he thinks such discussions are not very real, in that 'the military power of the United States is and will continue to be necessary to the defence of Europe for an indefinite period.' And, looking into the future, he believes that long after 'Europe will have reached political maturity or gained its optimum power in the military field,' the bonds of NATO will continue to function.

Has Vietnam changed all this? Brosio was after all talking about the stress of Cuba on an alliance which was not consulted, but responded quickly to another President's handling of that difficult situation. Brosio has made no more speeches since this one, but the NATO Council has dis- cussed Vietnam in restricted session in London this week. One hopes that Brosio's clear and tolerant voice was heard with the attention it deserves.

Previous page

Previous page