Dance

Bejart's ball

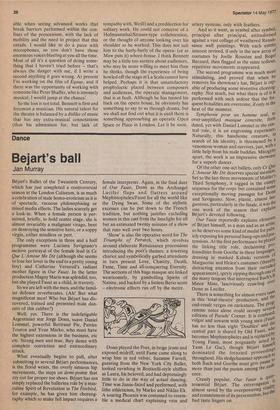

Jan Murray

Mart's Ballet of the Twentieth Century, which has just completed a controversial season at the London Coliseum, is as much a celebration of male homo-eroticism as it is of spectacle, vacuous philosophising or mixed media effects. The ladies scarcely get a look-in. When a female person is permitted, briefly, to hold centre stage, she is almost invariably a malignant virago, bent on destroying the sensitive hero, or a soppy virgin, either mindless or pert.

The only exceptions in three and a half programmes were Luciana Savignano's incisive portrayal of the female lead in Ce Que L'Amour Me Dit (although she seems to lose her lover in the end to a pretty young boy) and Catherine Verneuil's radiant mother figure in Our Faust. In the latter production Maguy Mann was splendid, too, but she played Faust as a child, in travesty.

So we are left with the men, and the familiar defence reverberates. (Ah! But what magnificent men! Who but Mart has discovered, trained and presented male dancers of this calibre?) Well, yes. There is the indefatigable Argentinian star Jorge Donn, suave Daniel Lommel, powerful Bertrand Pie, Patrice Touron and Yvan Marko, who must have the highest extensions in the business, etc etc. Strong men and true, they dance with complete conviction and extraordinary attack.

What eventually begins to pall, after submitting to several Mart performances, is the florid wrists, the overly sinuous hip movements, the steps on demi-pointe that cry out for proper toe shoes. Mart has not simply replaced the ballerina role by a masculine Spirit of Revolution in The Firebird, for example, he has given him choreography which to make full impact requires a female interpreter. Again, in the final duet of Our Faust, Donn as the Archangel Lucifer flaps and flutters around Mephistopheles/Faust for all the world like the Dying Swan. Some of the stylistic excesses can be put down to the French tradition, but nothing justifies excluding women in this cast from the limelight for all but an estimated twenty minutes of a show that runs well over two hours.

'Show' is also the operative word for The Triumphs of Petrarch, which revolves around elaborate Renaissance processions introducing the poet's themes: a towering chariot and symbolically garbed attendants in turn present Love, Chastity, Death, Fame, Time and all-conquering Eternity. The sections of this huge masque are linked wearisomely, by gambolling Spirits of Nature, and backed by a listless Berio score — electronic effects run off by the metre.

Donn played the Poet, in beige jeans and exposed midriff, until Fame came along to wrap him in red velvet. Suzanne Farrell, guesting from the New York City Ballet, looked ravishing in Botticelli-style chiffon as Laura, his beloved, and had depressingly little to do in the way of actual dancing. Time was Janus-faced and performed, with lithe athleticism, by Marko and Niklas Ek. A soaring Phoenix was costumed to resemble a medical chart explaining vein and artery systems, only with feathers. And so it went, as symbol after symbol, principal after principal, attitudinised against a vast collage of weathered Renaissance wall paintings. With each entr6e interest revived, if only in the new array of costumes by Joelle Roustan and Roger Bernard, then flagged as the same tedious, repetitive movements reappeared. The second programme was much more stimulating, and proved that when he removes his showman's hat, Mart is car able of producing some inventive choreography. Not much, but what there is of it is performed with such ardour that the fre' quent banalities are overcome, if only in the heat of the moment.

Symphonic pour un homme seul, t° over-amplified musique concrete, feels dated, yet with Daniel Lommel in the central ,role, it is an engrossing experience. Naturally, this handsome creature, in search of his identity, is threatened by a venomous woman and survives, just, with a little help from his male buddies. MisogrlY apart, the work is an impressive showcase for a superb dancer. Of the other one-act ballets, only Ce Qtie L'Amour Me Dit deserves special mention. Set to the last three movements of Mahler's Third Symphony, it sagged in the caturY sequence for thecorps but contained sortie exceptionally moving passages for Donn and Savignano. Slow, plastic, almost lag" guorous, particularly in the finale, it was the one work of the season that explairls Bejart's devoted following. Our Faust reportedly explains elements of Bejart himself, as a man and as an artist' so he deserves some kind of medal for pt icly exposing his personal hang-ups and Pre; tensions. At the first performance he OW' the linking title role, declaiming Pr°foundities from Goethe in three languages; dressing in masked Kabuki versions 0' Marguerite and Helen's costumes (therehYd distracting attention from their curtaile f appearances), spryly zipping through one the many tangoes that interrupted Bach's vf Minor Mass, 'lasciviously crawling ()ye Donn as Lucifer. There is something for almost everY talt: in this 'total-theatre' production, and "' end-result verges on caricature. The Prl ramme notes alone could occupy severl editions of Pseuds' Corner. It is confuse t vulgar and aswarm with young men (Faltse has no less than eight 'Doubles' and central part is shared by Old Faust, wlitri becomes Mephistopheles and is replace,d,,L Young Faust, most poignantly act' cue( t Yann Le Gac), though Bejart hip g5 dominated the frenzied proceedingv throughout. His sledgehammer approach lto both Bach and Goethe must give pause more than just the purists among the °LPence.

Crassly popular, Our Faust is q is tessential Mart. The extravaganza almost saved by the overpowering Vita Ole and commitment of its presentation, hi' bad taste lingers on.

Previous page

Previous page