The sandmen of Knutsford

Roy Kerridge

Aday of unending dreariness, grey clouds and shuttered shops, the new May Bank Holiday seemed to stretched into eternity. Some London parks held People's Festivals of various sorts, but fortunately attendance was not compulsory. Industry was disrupted, and at the Spectator a lost day meant one or two misprints getting through in the mad rush to catch up afterwards. Amid all this gloom and sor- row, one thought cheered me — that in a few days' time there would be a real May Day.

Knutsford, the little Cheshire town Mrs Gaskell described as 'Cranford', has one of the grandest May Day pageants in Britain. This is held on the first Saturday of the month, when all the shops are open, as well as the market, and an enormous fun fair blares away on the Heath. Taking the two- carriage train from Chester, I was surprised at the good manners of the schoolchildren who filled it. Many got out at Knutsford, the girls talking enthusiastically about church services. On the way to my friend's house in Gaskell Avenue, I basked in the gentle atmosphere of a town whose drivers 'Our son has programmed us out of his life.' stopped a zebra so much as glanced

a Older than the present May Day cere- mony at Knutsford, which was revived bY the 'Reverend Barnacle in 1864, is the an- cient custom of 'sanding'. For centuries, brightly coloured patterns of sand have greeted newly married couples as they step- ped from church. This custom is still kept up, and now extended to May Day, the sanding carried out by Mr Ray Veal, his son Colin, Mr Veal's brother-in-law Alf Giber!, and his son Jim, all salt-of-the-earth as well as sand-on-the-ground types- I called at Mr Veal's house on the evening before the festivities, and found it to be an unusual one, built into the side of the 18th- century Session House, as part of the wall that once surrounded the local prison. Mr Veal appeared in his shirt sleeves beneath a. large archway, and we stood on the cobbled driveway talking. He was a good-hurnonrea man with an alert face and a bush of grey h 'I came to these parts as a boy from Lin- colnshire, and I learned sanding from ivy late father-in-law, who had been doing It for nearly 30 years. I've been sanding for 20 years now, and my son is carrying it 01;' You know how the custom began,

don you? We've t

got oaldlidttalyesriitvmerushtehreavbeyb et lc; moor, and in That's why as hKing Canute had to ford across it on his way to Scotland or somewhere.- we're called Knut's F.ora• Anyway, the king had got over all right., when he stopped to shake the sand from his shoes. A bride and groom passed bY,cO mg from church, and the King said, ma' you have as much happiness and as rnanY children as there are grains of sands in MY shoes". Well, I hope they didn't have that many children, but that's how the custolni started. Weddings are still our main thing.,s live here in the Session House because my job to help the judges on and off w!ttnii their robes. I wear a grey uniform wi

"Court Keeper" written across it in gold braid when I'm at work.'

Saying goodbye to the Court Keeper, I Promised to meet him at six o'clock next morning to see the sanding. Judging by the state of the fun fair, which stood in a sea of mud, the story about King Canute was false. There was no sand to be seen anywhere in a town that slopes steeply down a hill towards a marsh known as the Town Moor. A nearby lake is known as the Mere. Knutsford chiefly consists of two parallel shopping streets on the hillside, known unofficially as Top Street and Bot- tom Street. They are connected by a great many alleys and the courtyards of former coaching inns.

May Day dawned bright and fair, the pavements wet from the night's rain, Which Mr Veal had assured me was good sand- ing weather, as it made the grains stick and show up brightly. Hurrying along Bottom Street, I soon found the four sanders at work, accompanied by Alf Gilbert's little grandson Stefan. Mr Veal slowly drove a van from place to place, the back open to reveal buckets of coloured sand which the men had dyed themselves. Working briskly, the sanders each filled a funnel known as a `tundish' with sand and, with one finger over the spout to control the flow, poured it out in sweeping arabesques several feet long up and down the pavements. Each curly line was accompanied, rainbow fashion, by lines in other colours, scarlet, chestnut, blue, green and natural white. Most of the large inscriptions, in block capitals or hand- writing,. read 'Long Live Our Royal May

Queen'.

As they worked with great dedication, the men chatted to one another, rolling cigarettes, remarking, 'E's a rum bugger' of some absent friend, and in general resembling unusually keen early-morning workmen rather than creative artists. Near- ly all the Bottom Street pubs had their doorways adorned with peacock-tail designs. We then drove out to the suburbs and council estates where members of the May Queen's court lived, all due for special treatment. Court members hung bunting outside their houses, for the whole occasion Was taken very seriously. What an extra- ordinary honour it must be for a 12-year-old girl to be chosen as May Queen and have the whole town at her feet! No wonder the former Queens kept their crowns and talked about their Day for the rest of their lives.

'Long Live Our Court Lady' and 'Long Live Maid Marion' were duly inscribed, and if sand-wishes alone would help, Knutsford was well on its way to being a town of octogenarians. A Court Lady ran after us with a crisp-looking envelope from her father Being associated with Royalty has its perks.

Back in the van, the sanders searched in vain for another court member who had neglected to put out coloured streamers and bLnting.

`1,f he don't take the trouble, why should we? someone said, disgruntled. The of-

fender had a sandless May Day. Hunched up in the van, as we hurtled through streets bright with almond blossom and fresh springtime greenery, I was fearful of getting dyed sand on my suit. No such calamity oc- curred, and soon we reached the home of Paula Williamson, the May Queen herself, which was decorated from top to bottom, with a banner on the roof and a triumphal arch of greenery in the front garden. Wasting no time, the sanding team drew a crown surrounded by rococo twiddles on the pavement, and added a little poem for good measure.

'Long May She Live, Happy May She Be, Blessed With Contentment And From Misfortune Free.'

Looking as harassed as a bride's father, Mr Williamson invited us all inside and we were each given a cup of coffee well laced with rum. Another envelope changed hands, and I felt some of the glory of being a dustman at Christmas in an unusually generous neighbourhood. Bidding the sandmen a final farewell, I was a little saddened to see that a shower of rain had softened the bright colours of the sand patterns, and washed the chestnut dye away into the gutters. Walked over by unheeding passers-by, the writing remained intact. Luckily the weather brightened, and with thousands of others I stood expec- tantly at the roadside waiting for the pro- cession to begin.

As the silver band struck up, horses with

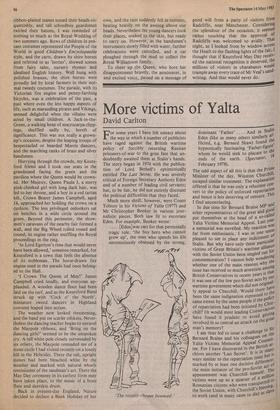

ribbon-plaited manes tossed their heads co- quettishly, and tall schoolboy guardsmen twirled their batons, I was reminded of nothing so much as the Royal Wedding of two summers ago. Rows of children in pea- sant costumes represented the People of the World in good Children's Encyclopaedia style, and the carts, drawn by shire horses and referred to as 'lorries', showed scenes from fairy tales, nursery rhymes and idealised English history. Well hung with polished brasses, the shire horses were proudly led by local farmers in their nor- mal tweedy costumes. The parade, with its Victorian fire engine and penny-farthing bicycles, was a celebration of the past, a past where even the less happy aspects of life, such as marauding pirates and Vikings, seemed delightful when the villains were acted by small children. A Jack-in-the- Green, a walking heap of macrocarpa clipp- ings, shuffled sadly by, bereft of significance. This was not really a grown- up's occasion, despite the leaping troops of bespectacled or bearded Morris dancers, and the marching ranks of brass and silver bandsmen.

Hurrying through the crowds, my Knuts- ford friend and I took our seats in the grandstand facing the green and the pavilion where the Queen would be crown- ed. Her Majesty, Queen Paula I, a merry pink-cheeked girl with long dark hair, was led to her throne, and a boy in a red tartan kilt, Crown Bearer James Campbell, aged 14, approached her holding the crown on a cushion. The less privileged onlookers sat on benches in a wide circle around the green. Beyond this perimeter, the show- men's caravans of the nearby fair formed a wall, and the Big Wheel rolled round and round, its engine rather muffling the Royal proceedings in the ring.

'In Lord Egerton's time that would never have been allowed,' someone remarked, for Knutsford is a town that feels the absence of its nobleman. The horse-drawn fire engine used in the parade had once belong- ed to the Hall.

'I Crown The Queen of May!' James Campbell cried loudly, and everyone ap- plauded. A wooden dance floor had been laid on the turf, and as the Knutsford Band struck up with 'Cock o' the North', miniature sword dancers in Highland costume leaped into action.

The weather now looked threatening, and the band put on scarlet oilskins. Never- theless the dancing teacher began to unravel the Maypole ribbons, and 'Bring on the dancing girls!' seemed to be the unspoken cry. A tall white pole closely surrounded by six others, the Maypole reminded me of a stone circle I had visited recently on a lonely hill in the Hebrides. There the tall, upright stones had been bleached white by the weather and marked with natural whorls reminiscent of the sandman's art. There the May Day ceremony in its earliest form may have taken place, to the music of a bone flute and deerskin drum.

Back in present-day England, Nature decided to declare a Bank Holiday of her own, and the rain suddenly fell in torrents, beating heavily on the awning above our heads. Nevertheless the young dancers took their places, soaked to the skin, but ready to carry on. However, as the bandsmen's instruments slowly filled with water, further celebrations were cancelled, and a car ploughed through the mud to collect the .Royal Williamson family.

To cheer up the Queen, who bore her disappointment bravely, the announcer, in and excited voice, passed on a message of

good will from a party of visitors from Radcliffe, near Manchester. Considering the splendour of the occasion, it seemed rather touching that the approval of Radcliffe was welcomed so avidly. That night, as I looked from by window across the Heath to the flashing lights of the fair, I thought that if Knutsford May Day receiv- ed the national recognition it deserved, the millions of visitors in charabancs would trample away every trace of Mr Veal's sand writing. And that would never do.

Previous page

Previous page