ARTS

Conservation

This precious stone

Perhaps the most striking lesson to be learnt from the Age of Chivalry exhibition which opened at the Royal Academy last week is, paradoxically, how unchivalrous we have been to our Gothic heritage. The survival of the magnificent collection of works of art on display is nothing short of miraculous. The catalogue makes fascinat- ing reading simply as a treasure hunt, tracing the provenance of pieces which surfaced unscathed despite the destruction wrought within a few yards of their resting place.

But the losses are enormous. Of pre- cious metals intended for ecclesiastical use not a single cross, candlestick, shrine, reliquary, monstrance or jewelled mitre is left. The desecration of shrines and sup- pression of monasteries produced nearly 300,000 oz. of plate and jewels for the Crown. It took 26 cartloads for Henry VIII's commissioners to remove the gold and silver from Canterbury, where the treasury was described by Erasmus only a few years before as having outshone that of Midas or Croesus. The French ambassador reported during the summer of 1542 that the Tower mint was working round the clock to reduce this booty to specie.

Sculpture suffered an even more visible fate, as countless statueless niches and defaced façades testify. The great rood screens spanning the centres of churches were so comprehensively destroyed that nothing of this sort remains in England. Individual pieces of wood sculpture were easily reduced to ashes by accident or design: the examples in the exhibition come from Scandinavia where English craftsmen worked and exported their wares. Stained glass was smashed; wall paintings distempered; precious vestments ripped asunder.

But if we look back with regret over acts of vandalism in the past, we cannot afford to be too complacent over our own con- servation record in recent years. A visit to any of our Gothic cathedrals — major land-marks in the development of Euro- pean culture — confirms the terrifying sums needed to keep up the Forth Bridge programme of restoration. The familiar sight of barometers bravely pegged outside venerable parish churches and chapels testifies to the enormous extent of the problem. The fact is that we are not living in a spiritual age and the upkeep of the fabric of churches is scarcely a vote- winner.

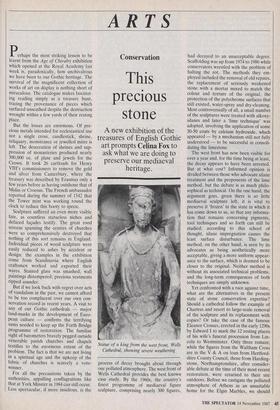

For all the precautions taken by the authorities, appalling conflagrations like that at York Minster in 1984 can still occur. Less spectacular, if more insidious, is the Statue of a king from the west front, Wells Cathedral, showing severe weathering process of decay brought about through our polluted atmosphere. The west front of Wells Cathedral provides the best known case study. By the 1960s, the country's finest programme of mediaeval figure sculpture, comprising nearly 300 figures, had decayed to an unacceptable degree. Scaffolding was up from 1974 to 1986 while conservators wrestled with the problem of halting the rot. The methods they em- ployed included the removal of old repairs, the replacement of seriously weakened stone with a mortar mixed to match the colour and texture of the original, the protection of the polychrome surfaces that still existed, water-spray and dry-cleaning. Most controversially of all, a small number of the sculptures were treated with alkoxy- silanes and later a 'lime technique' was adopted, involving the application of some 30-50 coats by calcium hydroxide, which appeared — by a mechanism still not fully understood — to be successful in consoli- dating the limestone.

The west front has now been visible for over a year and, for the time being at least, the decay appears to have been arrested. But at what cost? Informed opinion is divided between those who advocate silane treatment and the proponents of the lime method, but the debate is as much philo- sophical as technical. On the one hand, the argument goes, given there is so little mediaeval sculpture left, it is vital to preserve it 'frozen' in the state in which it has come down to us, so that any informa- tion that remains concerning pigments, tool techniques and so forth can still be studied; according to this school of thought, silane impregnation causes the least surface disturbance. The lime method, on the other hand, is seen by its advocates as being aesthetically more acceptable, giving a more uniform appear- ance to the surface, which is deemed to be closer to the original. Neither method is without its associated technical problems, and the long-term consequences of both techniques are simply unknown.

Yet confronted with a race against time, what are the alternatives in the present state of stone conservation expertise? Should a cathedral follow the example of Chartres and resort to large-scale removal of the sculpture and its replacement with copies? Or take the case of the famous Eleanor Crosses, erected in the early 1290s by Edward I to mark the 12 resting places of his wife's funeral procession from Lin- coln to Westminster. Only three remain; while the figures from the Waltham Cross are in the V & A on loan from Hertford- shire County Council, those from Harding- stone, Northamptonshire, after consider- able debate at the time of their most recent restoration, were returned to their site outdoors. Before we castigate the polluted atmosphere of Athens as an unsuitable home for the Elgin Marbles, we should direct our concern rather closer to home.

The picture is not wholly bleak. The Wells project, on a scale hitherto unknown in the United Kingdom, has at least re- sulted in a greater degree of technical and practical knowledge which can be applied elsewhere. The early-14th century corbels carved with crouching caryatid figures from the north porch of St Mary Redcliffe, Bristol, have been restored by the Wells Conservation Trust and can be seen in the exhibition. By underlining the extraordi- narily high quality of English mediaeval sculpture, the exhibition gives added im petus to display projects long in the incuba- tion. Sculpture from St Mary's Abbey, York will be incorporated in a new gallery at the Yorkshire Museum on its return from the show; thanks to conservation grants made in preparation for their loan, figures from the shrine of William of York have now been fully restored. A new display in the south transept triforium of Winchester Cathedral (part of the building Head of a king from Wells Cathedral, after conservation which has been neglected for centuries), will be devoted to some of the finest sculpture to be found outside Burgundy.

But these are glamorous works from major centres of mediaeval craftsmanship. More typical is the fate of the limestone reliefs of St Helena and St Martin disco- vered under the chancel pavement in All Saints Church, Mattersey, Nottingham- shire in the 18th century. Of exceptional quality, they possibly came originally from Mattersey Abbey and have been specially conserved for the exhibition. How they will be displayed on their return to the church, where they have stood dirty, neglected and vulnerable for decades beneath a leaking roof, has still to be decided.

We shall no doubt all marvel at the richly illuminated manuscripts on display, care- fully preserved in libraries over the centur- ies, and at the stars of the show like the King John cup from King's Lynn, the Bermondsey dish and the bridal crown of Blanche, daughter of Henry IV, from Munich. We can see fragments preserved from the magnificent scheme of painted decoration created for St Stephen's Chapel, Westminster in the mid-14th cen- tury, and mourn its destruction in Wyatt's remodelling of 1800. But we should also pause to think of the 2,000 medieval church wall paintings deteriorating in situ up and down the country at this moment. Instead of congratulating ourselves on our splendid heritage, we should ask ourselves what we intend to do to save it.

Dr Celina Fox is keeper of paintings, prints and drawings at the Museum of London.

Previous page

Previous page