A SYMBOL OF DECENCY

William Shawcross on the

bittersweet life and times of Alexander Dubcek

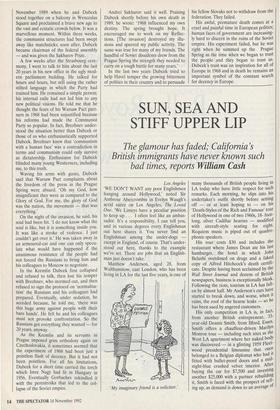

AT THE BEGINNING of 1990, a few weeks after Czechoslovakia's Velvet Revo- lution retrieved Alexander Dubcek from the memory hole to which the communists had consigned him, I went to Strasbourg to see him collect the Sakharov Prize from the European Parliament. It was a moving occasion. The President of the Parliament struck a chord when he said that meeting Dubcek for the first time felt 'as though we are greeting an old friend who has been with us over the last 20 years and who is inextricably bound up with our youthful memories'.

That is one reason why Dubcek's painful death is so sad and shocking to many of my generation. In 1968 he, his optimism and his brutal treatment by the Soviets had become part of the youth of millions of Europeans and the memory of him never went away. One of the great joys of the Velvet Revolution was seeing that memory made flesh.

At lunch that day in Strasbourg he and his wife spoke of their 20 years of enforced

exile in Slovakia. Anna had spent a lot of time in a cabin in the countryside; Dubcek had pottered around in a menial job in the Slovak Forestry Commission, under con- stant police supervision and subject to peri- odic torrents of abuse from the Party press. Perched on the edge of his chair, he talked through lunch with great verve, tense and excited at his refound freedom and prominence. He was astonished by the progress of the West. I asked him if, in his 20 years of solitude, he had, like another internal exile, Anna Akhmatova, concen- trated on the past, ignoring the future. He said no: he thought about the future, the present and the past. At the end of the meal everyone wanted to be photographed with him — this gentle, naïve but irreplace- able inspiration for Europe.

I had first seen him in August 1969, one year after the Soviets had invaded to crush the reforms of the Prague Spring. I was try- ing to research a biography of him; he was under constant surveillance and impossible to reach. Nor did he want to talk.

On the first anniversary of the invasion I was in Wenceslas Square as tanks, water- cannon and police charges swept protesters away. Dubcek, who was still nominally in office, was forced to endorse repressive emergency legislation which destroyed the last traces of his democratic reforms. A few days later, I was overjoyed to find myself on the same flight from Prague to Bratislava. Dubcek looked punch-drunk as he sat with a keeper on either side of him. I passed him a note (written in Czech with the help of my neighbour) saying how much he was admired in the West; at the end of the flight he shook my hand and bestowed his famous sad smile; his eyes were moist as almost everyone else on the plane greeted him.

In the next 20 years as a non-person, he never recanted his belief that the Prague Spring could have produced a decent com- munist system. But when Charter 77 was formed he disappointed many dissidents by declining to sign it, and Vaclav Havel began to emerge as the most prominent and courageous of those individuals pre- pared to oppose the regime. History, in Havers words, began again in

November 1989 when he and Dubcek stood together on a balcony in Wenceslas Square and proclaimed a brave new age to the vast and ecstatic crowds below. It was a marvellous moment. Within three weeks, the communist structures had been swept away like matchsticks; soon after, Dubcek became chairman of the federal assembly — and was given the Sakharov Prize.

A few weeks after the Strasbourg cere- mony, I went to talk to him about the last 20 years in his new office in the ugly mod- ern parliament building. He talked for hours and hours, but still using the rather stilted language in which the Party had trained him. He remained a simple person; his internal exile had not led him to any new political visions. He told me that he thought the fears of his Warsaw Pact part- ners in 1968 had been unjustified because his reforms had made the Communist Party so popular. In fact, Brezhnev under- stood the situation better than Dubcek or those of us who enthusiastically supported Dubcek. Brezhnev knew that 'communism with a human face' was a contradiction in terms and communism could only survive as dictatorship. Enthusiasm for Dubcek blinded many young Westerners, including me, to this truth.

Waving his arms with gusto, Dubcek said that Warsaw Pact complaints about the freedom of the press in the Prague Spring were absurd. 'Oh my God, how insignificant they were as compared to the Glory of God. For me, the glory of God was the nation, the movement — that was everything.' On the night of the invasion, he said, his soul had been hit. 'I do not know what the soul is like, but it is something inside you. It was like a stroke of violence. I just couldn't get over it.' He was taken away in an armoured-car and one can only specu- late what would have happened if the unanimous resistance of the people had not forced the Russians to bring him and his colleagues to Moscow to negotiate.

In the Kremlin Dubcek first collapsed and refused to talk, then lost his temper with Brezhnev, who stormed out, and then refused to sign the protocol on 'normalisa- tion' the Russians and his colleagues had prepared. Eventually, under sedation, he acceded because, he told me, 'there was this huge army against people with their bare hands'. He felt he and his colleagues must not provoke confrontation. So the Russians got everything they wanted — for 20 years, anyway.

As the Kremlin and its servants in Prague imposed grim orthodoxy again on Czechoslovakia, it sometimes seemed that the experiment of 1968 had been just a pointless flash of decency. But it had not been pointless. For all his limitations, Dubcek for a short time carried the torch which Imre Nagy had lit in Hungary in 1956. Eventually Gorbachev rekindled it with the perestroika that led to the col- lapse of the Soviet empire. Andrei Sakharov said it well. Praising Dubcek shortly before his own death in 1989, he wrote: '1968 influenced my own destiny. The spring brought hope. It encouraged me to work on my Reflec- tions. [The invasion] destroyed my illu- sions and spurred my public activity. The same was true for many of my friends. The handful of Soviet dissidents drew from the Prague Spring the strength they needed to carry on a tough battle for many years.'

In the last two years Dubcek tried to help Havel temper the growing bitterness of politics in their country and to persuade his fellow Slovaks not to withdraw from the federation. They failed. •

His awful, premature death comes at a cruel and painful time in European politics; human faces of government are increasing- ly hard to discern in the ruins of the Soviet empire. His experiment failed, but he was right when he summed up the Prague Spring as the time when we began to trust the people and they began to trust us. Dubcek's trust was an inspiration for all of Europe in 1968 and in death he remains an important symbol of the constant search for decency in Europe.

Previous page

Previous page