Architecture

Modernism at home

Alan Powers on the case for preserving Erno Goldfinger's Hampstead house

Hercule Poirot would not have felt particularly at home at 2 Willow Road, Hampstead, at least in his television per- sona. This house has been given the chance of immortality in the hands of the National Trust as a token example of 1930s Mod- ernism, and although the fictional detective haunts a succession of white-walled, flat- roofed architectural settings, this one is dif- ferent: a quieter and more mature man- ifesto of new architecture.

Houses belonging to the movement in architecture labelled 'Modern' and 'Inter- national' were never particularly common in England, although Agatha Christie prob- ably did know something about them, as a resident of the Isokon Flats in Lawn Road, Hampstead, an experiment in `Exis- tenzminimum' living by consenting intellec- tuals where the concrete architecture and the prevailing politics were tinted in vary- ing shades of pink.

Further up the hill from Lawn Road,

overlooking the edge of Hampstead Heath, stands the terrace of three houses in Wil- low Road designed in 1938 by the émigré Hungarian architect Erno Goldfinger, who may never have known Agatha Christie but seems unwittingly to have given his name instead to one of Ian Fleming's famous vil- lains. Goldfinger was a personality large in life and sometimes too hard for the English architectural establishment to accept. Trained in Paris in the 1920s under Auguste Perret, whom he revered, he came to London with his English wife Ursula in 1934 and lived at Willow Road until his death in 1987. Visitors could be regaled with his stories of Adolf Loos and Le Cor- busier, and equally by the collection of pic- tures by friends like Max Ernst or Henry Moore. Corbusier's colleague Charlotte Perriand wrote in 1983 that Willow Road recaptured Paris of the Twenties for her, `cette époque unique, car elle fut construc- tive des temps modernes'. Willow Road was part of the émigré cul- ture of Hampstead before and after the second world war, a product of unique his- torical circumstances and geographical accident, but one which produced a lively exchange of political and artistic ideas and lifted London out of its habitual isolation from the Continent. Goldfinger sided with the Surrealists against the abstract Con- structivists, held an exhibition in aid of Soviet Russia in the house in 1942 and sal- lied forth from here in the 1960s to build some of the tallest blocks of public housing in London. `They were not tall enough,' he would say. 'There are too many bad archi- tects around, but I am a very good archi- tect.'

Posterity has sometimes been reluctant to take him at his word, but Erno Goldfin- ger has had eloquent defenders, notably the architect James Dunnett who worked for him, and Gavin Stamp, who, against his expectations, was charmed by him. It is

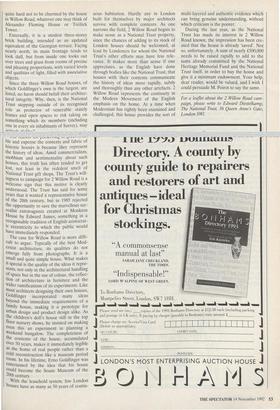

Interior of the house at 2 Willow Road, Hampstead quite hard not to be charmed by the house in Willow Road, whatever one may think of Alexander Fleming House or Trellick Tower.

Externally, it is a modest three-storey brick building, intended as an updated equivalent of the Georgian terrace. Facing nearly north, its main frontage tends to look dull, but from inside one looks out over trees and grass from rooms of precise and pleasing proportions, with varied levels and qualities of light, filled with associative objects.

Since the three Willow Road houses, of which Goldfinger's own is the largest, are listed, no harm should befall their architec- tural integrity. Why, then, is the National Trust stepping outside of its recognised role as protector of venerable stately homes and open spaces to risk taking on something which its members (including one in every six inhabitants of Surrey), may

Artianal.,

••••• ,C4.3l, I 1V1 crab LA • gtt,

ble and expense the contents and fabric of historic houses is because they represent the history of ideas. Amid commercialism, snobbism and sentimentality about such houses, this truth has often tended to get lost, not least in the redolent smell of National Trust gift shops. The Trust's will- ingness to campaign for 2 Willow Road is a welcome sign that this motive is clearly understood. The Trust has said for some years that it wanted a representative house of the 20th century, but in 1985 rejected the opportunity to save the marvellous sur- realist extravaganza created at Monkton House by Edward James, something in a recognisable tradition of English aristocrat- ic eccentricity to which the public would have immediately responded.

The case for Willow Road is more diffi- cult to argue. Typically of the best Mod- ernist architecture, its qualities do not emerge fully from photographs. It is a small and quite simple house. What makes it special is the quality of the ideas it repre- sents, not only in the architectural handling of space but in the use of colour, the reflec- tion of architecture in furniture and the Wider ramifications of its experiments. Like most architects designing their own houses, Goldfinger incorporated many ideas beyond the immediate requirements of a family house, making it a prototype for urban design and product design alike. As the children's doll's house still in the top floor nursery shows, he insisted on making even this an experiment in planning a weekend bungalow. The completeness of the contents of the house, accumulated Over 50 years, makes it immediately legible as the home of real people rather than a cold reconstruction like a museum period room. In his lifetime, Erno Goldfinger was entertained by the idea that his house Could become the Soane Museum of the 20th century.

With the leasehold system, few London houses have as many as 50 years of contin- uous habitation. Hardly any in London built for themselves by major architects survive with complete contents. As one narrows the field, 2 Willow Road begins to make sense as a National Trust property, since the chances of adding to its stock of London houses should be welcomed, at least by Londoners for whom the National Trust's other efforts may have less rele- vance. It makes more than sense if one appreciates, as the English have done through bodies like the National Trust, that houses with their contents communicate the history of ideas more rapidly, subtly and thoroughly than any other artefacts. 2 Willow Road represents the continuity in the Modern Movement of the English emphasis on the home. At a time when Modernism has rightly been examined and challenged, this house provides the sort of multi-layered and authentic evidence which can bring genuine understanding, without which criticism is the poorer.

During the last year, as the National Trust has made its interest in 2 Willow Road known, the impression has been cre- ated that the house is already 'saved'. Not so, unfortunately. A sum of nearly £500,000 needs to be raised rapidly to add to the sums already committed by the National Heritage Memorial Fund and the National Trust itself, in order to buy the house and give it a minimum endowment. Your help, dear reader, would be valued, and I wish I could persuade M. Poirot to say the same.

For a leaflet about the 2 Willow Road cam- paign, please write to Edward Diestelkamp, The National Trust, 36 Queen Anne's Gate, London SWL

Previous page

Previous page