CHESS

Brilliance and blunders

Raymond Keene

No one believed that it could possibly happen. After two decades in the wilder- ness, the mercurial American genius, Bob- by Fischer, has made a comeback. For twenty years, after decisively beating Soviet World Champion Boris Spassky in the most celebrated chess match of all time at Reykjavik in 1972, Fischer did not play a single game of match or tournament chess.

The play in their rematch has been a mixture of brilliance and blunders. By general consent the first game was a masterpiece, which astounded experts and grandmasters alike. It seemed that Fis- cher's absence for twenty years from the chessboard had in no way blunted the ferocity of his mental cutting edge. Even better was to come, in the shape of game 11. This was a game where Spassky de- fended tenaciously and ingeniously, yet was bowled over by the dazzling force of Fischer's attack.

Punctuating such masterpieces were the horrors of games 5 and 19, where Fischer drifted planlessly. These were games scarcely to be distinguished from those of amateur level. World Champion Gary Kasparov has dismissed all the games as inferior and not up to championship stan- dard but, to quote Mandy Rice-Davies, 'He would, wouldn't he?' Fischer is the only champion in the 100-plus years of the official championship who can seriously challenge Kasparov's position as the strongest and most highly-rated player of all time. These two are the pinnacle of chess. On paper, Kasparov's rating is the higher; yet it is Fischer who has established himself as the greatest personality amongst the public at large.

Now that Fischer has overcome Spassky for the second time, will he go back to sulk in his Pasadena tent for another twenty years? Alternatively, will his sanction- busting activities, playing in Belgrade in defiance of UN sanctions, even permit him to re-enter the United States? It is possible that he might stay in Belgrade, move to Budapest, or even join Boris Spassky in exile in Paris.

The only satisfactory outcome for the chess world is for Fischer now to take on an opponent superior to Boris Spassky, one who will really test him, preferably Nigel Short. Ultimately, a Fischer-Kasparov match would resolve the question of who is the greatest warrior of the mind on the planet.

Spassky — Fischer: 'World Championship Match', Belgrade, Game 30; King's Indian De- fence.

1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 g6 3 Nc3 Bg7 4 e4 d6 5 f3 0-0 6 Be3 Nc6 7 Nge2 a6 8 h4 h5 9 Ncl Nd7 This is much more in keeping with the hypermodern theory of the Samisch variation than the 9 . . . e5 Fischer had tried in previous games. 10 Nh3 a5 11 a4

Position after 12 . . . b6

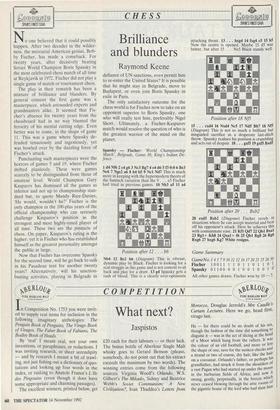

NM 12 Be2 b6 (Diagram) This is vibrant, dynamic play by Black. Fischer is looking for a real struggle in this game and is not content to sit back and play for a draw. 13 g4 Spassky gets a rush of blood. This is a clearly over-optimistic attacking thrust. 13 . . . hxg4 14 fxg4 c5 15 h5 Now the centre is opened. Maybe 15 d5 was better, but after 15 . . Ne5 Black stands well.

Position after 18 Nf5

15 . . . cxd4 16 Nxd4 Nc5 17 Nd5 Bbl 18 Nf5 (Diagram) This is not so much a brilliant but misguided sacrifice as a desperate last-ditch throw. Spassky realises his position is crumbling and acts out of despair. 18 . . . gxf5 19 gxf5 Bxd5

Position after 20 . . . Bxb2

20 exd5 Bxb2 (Diagram) Fischer revels in situations where he can accept material and beat off his opponent's attack. Here he achieves this with consummate ease. 21 Kfl Qd7 22 Qbl exal 23 Rgl + Kh8 24 Qxal+ f6 25 Qbl Rg8 26 Rg6 Rxg6 27 hxg6 Kg7 White resigns.

Game Summary GameNo. 1 4 5 7 9 10 11 12 16 17 20 21 25 26 30

Fischer 10011 1 1 0 1 1 0 1 1 0 1 Spassky 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 1 0 0 1 0

All other games drawn. Fischer won by 10 — 5.

Previous page

Previous page