Masterpieces in miniature

Andrew Lambirth

Adam Elsheimer: Devil in the Detail Dulwich Picture Gallery, until 3 December Richard Wilson The Curve, Barbican, until 14 January 2007 Regular readers of this column will be aware that I champion small exhibitions which combine judicious selection with sufficient breadth to give an adequate representation of the artist under discussion. With Adam Elsheimer (1578–1610) there is no choice: the fullest retrospective must needs be a small exhibition. An artist who worked slowly, suffered from depression and died young, his total output was 34 paintings. Thirty of these have been gathered together at Dulwich, supported by a lavish publication from Paul Holberton Publishing (£35 hardback and £22.50 soft cover), which is the first decent book on Elsheimer in English for some 30 years. But Elsheimer, who painted on the ultra-reflective surface of copper, made tiny, immensely detailed pictures which do not reproduce at all well. They need to be seen to be fully appreciated.

The show begins with the ‘Frankfurt Tabernacle’, which deals with the finding and exaltation of the True Cross, a narrative in seven panels, and Elsheimer’s most important commission, as far as we know. A marvel of clarified complexity, it at once reminds us of its painter’s friendship with Rubens, and distances itself from him. Elsheimer was German, but had travelled to Venice in 1598, spending two years there studying Titian, Giorgione and Tintoretto, before moving on to Rome, where he died a mere ten years later. Rubens got to know him in Rome, and was a great admirer of his work. (‘He has died in the flower of his art, while his corn was still in the blade,’ he lamented.) In fact, Elsheimer exerted a considerable influence over the key figures of the 17th century — Rubens himself, Rembrandt and Claude Lorrain. For such a small output, the effect was prodigious.

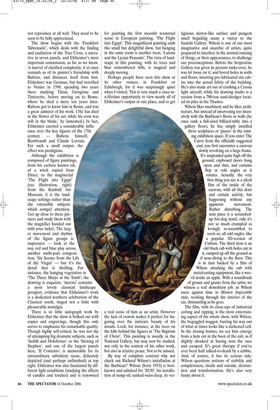

Although the exhibition is composed of figure paintings, from his earliest known oil, of a witch copied from Dürer, to the magisterial ‘The Flight into Egypt’ (see illustration, right) from the Kimball Art Museum, it is the land scape settings rather than the ostensible subjects which compel attention.

Get up close to these pic tures and study them with the magnifier handed out with your ticket. The larg er movement and rhythm of the figure groups is impressive — look at the way red and blue play across another multi-part composi tion, ‘Six Scenes from the Life of the Virgin’ — but it’s the detail that is thrilling. For instance, the hanging vegetation in ‘The Three Marys at the Tomb’; the drawing is exquisite. ‘Aurora’ contains a most lovely classical landscape prospect, evidence that Elsheimer’s work is a dedicated northern celebration of the Classical south, tinged not a little with pleasurable nostalgia.

There is so little autograph work by Elsheimer that the show is bulked out with copies and engravings, though this only serves to emphasise his remarkable quality. Though highly self-critical, he was not shy of attempting big dramatic subjects, such as ‘Judith and Holofernes’ or the ‘Stoning of Stephen’, and one of the largest panels here, ‘Il Contento’, is memorable for its extraordinary subsidiary scene, delicately depicted (and perhaps unfinished) at top right. Elsheimer was also fascinated by different light conditions (studying the effects of candles and torches) and is renowned for painting the first moonlit nocturnal scene in European painting, ‘The Flight into Egypt’. This magnificent painting ends this small but delightful show, but hanging in the same room is another treat, ‘Latona and the Lycian Peasants’. The vista of landscape in this painting, with its trees and blue remembered hills, is magical and deeply moving.

Perhaps people have seen this show at its other venues, in Frankfurt or Edinburgh, for it was surprisingly quiet when I visited. This is very much a once-ina-lifetime opportunity to view nearly all of Elsheimer’s output in one place, and to get a real sense of him as an artist. However the lack of crowds makes it perfect for lingering over the intricate beauty of his details. Look, for instance, at the trees on the hills behind the figures in ‘The Baptism of Christ’. This painting is usually in the National Gallery, but may now be studied, not only in the context of his other work, but also in relative peace. Not to be missed.

By way of complete contrast why not check out Richard Wilson’s installation at the Barbican? Wilson (born 1953) is bestknown and admired for ‘20:50’, his installation of sump oil, tanked waist-deep, its ver tiginous mirror-like surface and pungent smell beguiling many a visitor to the Saatchi Gallery. Wilson is one of our most imaginative and anarchic of artists, quite prepared to interfere in the normal running of things, or their appearances, to challenge our preconceptions. Before the Serpentine Gallery was given its present make-over, he was let loose on it, and bored holes in walls and floors, inserting pre-fabricated site cabins into the actual fabric of the building. He’s also made art out of crushing a Cessna light aircraft, while his drawing studio is a section from a 700-ton sand-dredger located on piles in the Thames.

Wilson likes machinery and he likes architecture, but instead of intervening too intensively with the Barbican’s floors or walls (he once sank a full-sized billiard-table into a gallery floor), he has simply installed three sculptures or ‘pieces’ in the existing exhibition space. If you enter The Curve from the officially suggested end, you first encounter a caravan slowly revolving on a large frame. It’s suspended quite high off the ground, cupboard doors bang open and shut, and curtains flop at odd angles as it rotates. Actually, the very first thing you see is a silent film of the inside of the caravan, with all this door and curtain activity, but happening without any apparent movement. Rather disturbing. The next piece is a scrunchedup hot-dog stand, only it’s not so much crumpled as lovingly re-assembled to seem so; all odd angles, like a popular 3D-version of Cubism. The third item is an old black cab with holes cut in it, ramped up off the ground as if nose-diving to the floor. This is in turn backed by a film of Wilson attacking the cab with metal-cutting equipment, like a weevil inside an apple. With a soundtrack of groans and grunts from the artist, we witness a real demolition job, as Wilson races against time in Mission Impossible style, working through the interior of the car, dismantling as he goes.

The film, with its close-ups of industrial cutting and ripping, is the most entertaining aspect of the whole show, with Wilson, the begoggled maggot, busting his way out of what at times looks like a darkened cell. In the closing frames, we see him emerge from a hole cut in the boot of the cab, as if slightly shocked at having won the race and escaped. It’s great therapy if you’ve ever been half talked-to-death by a cabbie. And, of course, it has its serious side. Wilson questions notions of stability and completeness, inside and outside, destruction and transformation. He’s also very funny about it.

Previous page

Previous page