SIMPSON'S

IN•THE-STRAND

SIMPSON'S

IN.THE-STRAND

CHESS

Latrunculi

Raymond Keene

A POSSIBLE ancestor to chess hit the headlines during the past week when a 2,000-year-old board game popular with Roman imperial troops was discovered at Colchester. On earlier occasions, boards have been found etched onto classical remains, such as Hadrian's Wall, but no one had ever discovered the vestiges of a gaming table with the pieces also set out in what appeared to be a near-starting posi- tion. There have been earlier attempts to reconstruct classical games, but the Col- chester discovery renders these obsolete.

This startling find comprised a board measuring 22 by 14 inches, hinged in the middle and with L-shaped metal corner pieces. It appeared to be chequered, though much of the wood itself had rotted away, and there was no particular evidence that the squares themselves were coloured in black and white alternately, as on a mod- em chessboard. The pieces, neatly lined up in their initial martial array, were attractive white and blue glass lozenges, similar to the kind of peppermint one is often offered on leaving a restaurant.

How was the game played? I have searched classical art and literature for ref- erences, as well as comparing possibilities with other games of around the same peri- od, such as the Welsh Gwydbyll, the Irish Fidchell (both meaning 'wood sense') and the Viking Hnefatafl, meaning the King's Game. The likely designation of the Colchester discovery is Ludus Latruncu- lorum, or the Soldiers' Game, A vase of around 500 BC, with versions both in the Vatican and the British Museum, depicts Ajax and Achilles at the siege of Troy play- ing a board game where the dimensions and shape of the pieces look remarkably similar to this. Plato's Republic distinguish-

es between board games of chance (kubeia) and those of skill (petteia), in which block- ade of the opponent's possibilities becomes important. Finally, the 2nd-century AD commentator, Pollux, discusses a game popular in the Roman Empire, in which the capture method involves placing two of one's own men on either side of a hostile unit, the so-called gendarme, epaulette or escort mode of capture.

The board from Colchester appears to have been 12 squares by 8 in dimension, with all the men being of equal value. Their lozenge-like shape suggests to me that any sort of promotion on reaching the oppo- nent's back rank would have been unlikely. Promotion in draughts (where, unlike chess, all the pieces are the same) is achieved by balancing one piece on top of the other. In Latrunculi, such promotion would not function, since the counters would not fit on top of one another.

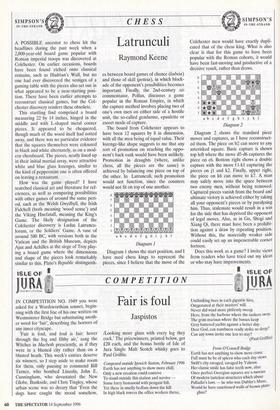

Diagram I Diagram 1 shows the start position, and I have used chess kings to represent the pieces, since I believe that the move of the

Colchester men would have exactly dupli- cated that of the chess king. What is also clear is that for this game to have been popular with the Roman cohorts, it would have been fast-moving and productive of a decisive result, rather Than draws.

Diagram 2 Diagram 2 shows the standard piece moves and captures, as I have reconstruct- ed them. The piece on b2 can move to any asterisked square. Basic capture is shown top left where the move d5-d6 captures the piece on c6. Bottom right shows a double capture with the move 11-k1 capturing the pieces on jl and k2. Finally, upper right, the piece on k6 can move to k7. A man may safely move into the space between two enemy men, without being removed. Captured pieces vanish from the board and ultimate victory is achieved either by taking all your opponent's pieces or by paralysing him. Thus, stalemate would result in a win for the side that has deprived the opponent of legal moves. Also, as in Go, Shogi and Xiang Qi, there must have been a prohibi- tion against a draw by repeating position. Without this, the materially weaker side could easily set up an impenetrable corner fortress.

Does this work as a game? I invite views from readers who have tried out my ideas or who may have improvements.

Previous page

Previous page