CHERCHEZ LA FEMME

Minette Marrin examines the

use Mrs Thatcher has made of her gender

TRYING to have things both ways, com- monly ascribed to women, is much more typical of politicians. Either way, politician and woman, Mrs Thatcher certainly does it. In particular, she plays the card of her gender both ways. She insists on being seen as a woman, with a woman's mind, but she also insists, at other times, that the differ- ence makes no difference.

As .a result she presents an irritating conundrum. Both in public and in private she very obviously displays a rather awe- some femininity, none the less real for having been embellished by public rela- tions men. Her enthusiasm for discussing the finer points of ironing and the price of apples appears, though it may serve her well with women voters, to be quite genuine. On the other hand her most striking qualities are not peculiarly female; a description of a politician as courageous, resilient, single-minded and a bit of a bully would not immediately suggest a woman. Yet many people who know Mrs Thatcher are convinced that her gender is very important, without being able (or willing) to say clearly what they mean.

It seems to me rather trivial to talk (as many do) about her feminine charm, her exploitation of her sexual appeal and her flirtatiousness. All successful people need some form of charm, some form of animal charisma, and overworked charm is just the politician's deformation professionelle — marked but superficial. Equally the extensive discussion in newspapers and on television of Mrs Thatcher's hair, teeth, clothes and diet seems empty. Obviously, in a conventional sense Mrs Thatcher is (on this evidence) very feminine. She enjoys

being a girl. She likes pretty underwear, she knows how to keep the bows on her frocks puffed up with tissue paper and she wears Denis's pearls to flatter her good complexion. She is a good-looking and, latterly, an elegant woman. If all this is relevant to her success or failure as a prime minister, it can only be in the sympathetic impression it makes on some voters.

However, among her peers it has not mattered one way or the other; Golda Meir and Shirley Williams were not held back by their lack of conventional chic nor was Barbara Castle advanced by her possession of it. The point about femininity, as distinct from femaleness, is that it is so obviously conventional. I am sure Mrs Thatcher would adopt a Mao suit and a cultural revolution bob, if she thought it

suitable, or if it answered her purposes. As it is, she has tinkered with her hair and her voice and her manner to create a softer, less aggressive persona.

The question of appeasement is the only interesting aspect of the public manipula- tion' of Mrs Thatcher's femininity. The difficulty with being a woman in power in a society like this is that you cannot afford to seem either too strong or too weak, a problem with stereotypes that would not confront a male prime minister. Mrs Thatcher's particular feminine style is almost successful at impressing and appeasing at the same time. The combina- tion of rather severe suits with noticeably high heels, giving conflicting messages of decisiveness and helplessness, is a classic ploy. Mrs Thatcher's real interest in domestic detail must genuinely endear her to some women who might otherwise resent her Olympian competence. So may her occasional performances as Mrs Aver- age, as in, 'It hasn't worn me down — no, no, no. Mums take a lot of wearing down, thank goodness.' (Woman's Own, 1987.)

In this sense Mrs Thatcher's femininity has simply been a superficial means of dealing with the disadvantage of being female. The interesting question about her gender is how, less superficially, being female has worked for or against her..

In one way it has helped. Mrs Thatcher may say she owes nothing to contemporary feminism, but surely the fact is that she owed her rapid early rise to tokenism, to reverse discrimination. She would not have been able to get into position for the leadership had there not been a shortage of Conservative women; she became a junior spokesman almost as soon as she had been elected, for that reason. It was clever of her to have taken advantage of this, and to have been one of those few, able Tory women. But the fact remains that her male-dominated party and Britain's voters would have felt no need and little inclina- tion to support her had it not been for years of persistent pressure from feminists.

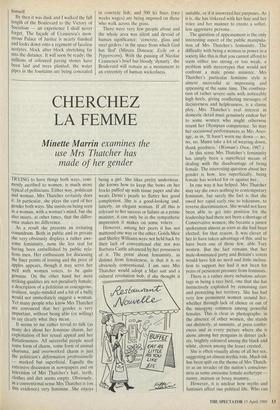

There is a rather more nebulous advan- tage in being a rare bird, one that she has instinctively exploited by remaining rare and protecting her territory. She has had very few prominent women around her, whether through lack of choice or out of the misogyny common among powerful females. This is clear in photographs: in the absence of other women, she stands out distinctly, at summits, at press confer- ences and in every picture where she is alone among her penguins in dinner jack- ets, brightly coloured among the black and white, cloven among the lesser crested.

She is often visually alone of all her sex, suggesting an almost mythic role. Much ink has been spilt on the theme of Mrs Thatch- er as an invader of the nation's conscious- ness as some awesome female archetype - nanny, matron or bossy mummy. • However, it is unclear how myths and fantasies affect our political life. Who can presume to say what deep-seated desires and animosities are touched by the very idea of Mrs Thatcher? Tempting though it might be to discuss her as Britannia or the Witch of Endor, this must all he pure speculation.

Mrs Thatcher's imposing figure, symbo- lic or not, may dominate the group photo- graphs, but she is still isolated from the groups. As a woman she cannot he clubb- able, cannot he part of the old-boy net- work; she would he as welcome at White's as a male nurse on an obstetrical ward. She does not fit well into the male-dominated House of Commons. She cannot he part of the male establishment web of loyalty and convention. Someone else might have found this subtle exclusion a disadvantage; Mrs Thatcher positively makes the most of her apartness; she would not want to belong. Unimpeded by such ties, she seems (and is said) to have a deeper loyalty to her own convictions than to the continuing compromises of the old-boy network. 'She won't put up with it,' said one observer. 'That's why we've had so many people broken and rolled over, sackings on the telephone.... I've lived through years of prevarication based on the old-boy net- work. She's the negation of all the Carlton Club is supposed to stand for. That's her greatest strength.'

If it is a strength it is one in which the accident of gender comes together with something more essentially female: Even if Mrs Thatcher were magically to appear in clubland in perfect male disguise, she would still he entirely out of place, because of her many traditionally female qualities. Like many housewives, she has few (if any) interests outside her job, few intellectual or artistic pleasures and very little sense of repose. Like the great majority of women she is not witty or even humorous. She cannot, reportedly, tell a funny story and I do not think she has ever made a really memorable remark in public. Her single- minded intensity would not go well with the educated establishment's love of word- play and jokes, of disengaged verbal spar- ring and double meanings.

As Mrs Thatcher might well agree, these verbal games underlie one of the foremost vices of the British establishment; they can lead to a temptation to mistake rhetoric for action, or at least to think that others will, and to flannel. Mrs Thatcher was not brought up to this. She is a person who will call a nettle a nettle and grasp it resolutely. Perhaps this is what John Vincent meant when he wrote in 1982 that she had the great benefit of not having spent her formative years before the age of 40 in the company of very clever men.

I suspect Mrs Thatcher, like many women, is impatient of masculine clever- ness. When asked once about a joke she had inadvertently made in the House of Commons, she replied that 'men are more conscious of double meanings than women. Women are slow to see double

meanings.' She proved this recently in her own case, in her delightfultribute to Lord Whitelaw: 'Every prime minister needs a Willie.' This insensitivity to ambiguity might to some suggest a limitation in female thinking, but not to Mrs Thatcher. Doesn't a double meaning come very close to a forked tongue, after all? Don't double meanings — and Oxford rhetoric — have a lot to do with doubt and indecision, ambivalence and prevarication?

It is quite plain that Mrs Thatcher thinks single-mindedness, decisiveness and practi- cality are some of the greatest virtues of her approach to life, as they are of the good housewife's. Her 'posture as house- keeper to the nation may have become one of her greatest clichés but it is none the less genuine for all that; she clearly believes in her housewife's homilies — cut your coat according to your cloth, save up for a rainy day, the labourer is worthy of his hire, mind your manners, fine words butter no parsnips, a woman's work is never done, take care of the pence, if you want some- thing done, properly do it . yourself. She lives by all this. 'Her most interesting, her most unusual quality is a real zest for detail,' according to one dispassionate observer. 'Her positive'dissatisfaction with compromise, with forms of words is not so much single-mindedness, ,or being blink- ered, as her insistence on coming back to details. She doesn't forget a thing.' She is a mistress of minutiae, from remembering a cake for some child to astonishing her civil servants with her command of facts, from making her name at the committee stage of a finance bill by her remarkable grasp of detail to her bossy, restless fussing about domestic trivia at Downing Street. • What drives her, it seems, is an inability to leave things alone, a reluctance to delegate, a 'need to keep everything under control, an impatience, amidSt her own ceaseless activity, with playfulness or other possibilities, as if people were metaphor- ically threatening to muddy her nice clean

floor. It is all too common to see this in the minds of other less remarkable women, who have lived more limited lives; it is odd to see it in someone who has been so fiee to choose her own, life. Is it possible that Mrs Thatcher's perspective doesn't really extend beyond -the practical and the domestic? Is it Possible,that mind and soul she is the housewife rampant? For all her triumphs in a man's world, Mrs Thatcher corresponds oddly closely to the old- fashioned female of the conventional stereotype. In particular her thinking seems to display the narrowness and teduc- tivenesS of which women have always been accused. -

Reductive or not, female or not, this cast of mind has served her well in the past; when the obstacles in front of her were clear and concrete. She has unswervingly faced and overcome opposition from her party, from her ministers, from civil ser- vants and from the unions, in a way that no mere man haS been able to do. She has been immensely practical in her achieve- ments. Having a certain simplicity, or crudity of concept, has made her enor- mously effective.

But now having. ticked many of the major practical problems off her list she has got down to the More nebulous ones, as she is well aware. They mostly have to do with the question of 'society', a concept which, absolutely typically, she has -found hard to deal with. Indeed until recently she couldn't he doing with it at all. But now in the midst of all her successes she is forCed to ask herself intractable questions about it. Richer and 1-astier? Why more crime? CenSorship for television porn but a free market for television drivel? The limita- tions of individual freedom'?

Moralising on these subjects .shows Mrs Thatcher in a poor light. She has often been unimpressive on the subject of broad- casting, for instance, and her remarks to the nation from Edinburgh on her religious faith did not reveal her mind at its most admirable; for instance, as Enoch Powell pointed out . at the time, 'only someone whOse view of life is highly simplified and conventional could assert that "we simply cannot delegate the exercise of mercy to others"'. (Mrs Thatcher in this vein is an embarrasSment to her supporters.)

Muddled, limited thinking, attached to unswerving convictions, is not peculiar to women. But it' is surely recognisably female. Previous ptiMe ministers have either been more intellectually aware, or less moralistic. That is probably why in important . ways they have done less well than Mrs Thatcher. But the tide, as Mrs Thatcher senses, has been turning. The questions facing her demand qualities she has not shown much of so far — a capacity for doubt, for unconventional. responses, for compromise, letting he and the wider view. If she does not find these strengths, her great achievements may be. eclipsed by the qualities that made them possible.

Previous page

Previous page