BOOKS

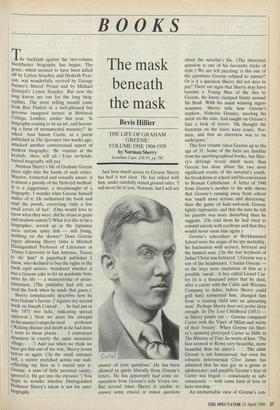

The mask beneath the mask

Bevis Hillier

THE LIFE OF GRAHAM GREENE: VOLUME ONE 1904-1939 by Norman Sherry

Jonathan Cape, f16.95, pp.783

The backlash against the two-volume blockbuster biography has begun. The genre, which seemed to have been killed off by Lytton Strachey and Hesketh Pear- son, was wonderfully revived by George Painter's Marcel Proust and by Michael Holroyd's Lytton Strachey. But now the long knives are out for the long biog- raphies. The most telling assault came from Ben Pimlott in a well-phrased but Perverse inaugural lecture at Birkbeck College, London, earlier this year. is biography ceasing to be an art, and becom- ing a form of monumental masonry?' he asked. And Simon Curtis, in a poem published in The Spectator two weeks ago, attacked another controversial aspect of modern biography: 'Be voyeurs at the keyhole, then; tell all: / Your no-holds- barred biography will pay.'

Norman Sherry's life of Graham Greene plays right into the hands of such critics. Massive, footnoted and sexually aware, it is almost a parody of the Holroyd method. It is a juggernaut, a dreadnought of a biography. I wonder what Greene himself makes of it. He authorised the book and read the proofs, correcting 'only a few small errors of fact'. (One would love to know what they were: did he strain at gnats and swallow camels?) What is it like to be a biographer, served up as the Japanese serve certain spiny fish — still living, writhing on the skewer? Does Greene regret allowing Sherry (who is Mitchell Distinguished Professor of Literature at Trinity University in San Antonio, Texas) to 'do' him? A paperback publisher I know, who declined to buy the rights to the book sight unseen, wondered whether it was a Greene joke to let an academic bore write his life — a masterstroke of misin . formation. (The publisher had still not read the book when he made that guess.) Sherry complacently describes how he Won Greene's favour. ('Against my second book on Joseph Conrad . . . he had put in July 1971 two ticks, indicating special approval.') Next we meet the intrepid in-his-master's-steps-he-trod professor ('Risking disease and death as he had done I went to those places . . . I contracted dysentery in exactly the same mountain village. . . .') And just when we think we have got him out of the way, Sherry looms before us again. ('In the small entrance hall, a mirror stretched across one wall, reflecting my face as I stared into it. Greene, a man of little personal vanity, ignored it. He got into the elevator.') You begin to wonder whether Distinguished Professor Sherry's talent is not for auto- biography. Just how much access to Greene Sherry has had is not clear. He has talked with him, under carefully stated ground rules: 'I will never lie to you, Norman, but I will not answer all your questions.' He has been allowed to quote liberally from Greene's letters. He has apparently had some co- operation from Greene's wife Vivien too. But several times Sherry is unable to answer some crucial or minor question about the novelist's life. (The rhetorical question is one of his favourite tricks of style.) We are left puzzling: is this one of the questions Greene refused to answer? Or is it a question Sherry did not dare to put? There are signs that Sherry may have become a Young Man of the Sea to Greene, his knees clamped firmly around his head. With his usual winning ingen- uousness, Sherry tells how Greene's nephew, Nicholas Dennys, meeting his uncle on the stair, had caught on Greene's face a look of terror. 'He thought the footsteps on the stairs were yours, Nor- man, and that an interview was to be undergone.'

This first volume takes Greene up to the age of 35. Some of the facts are familiar from his autobiographical books, but Sher- ry's delvings reveal much more than Greene has done about the two most significant events of the novelist's youth: his breakdown at school and his conversion to Roman Catholicism. A letter of 1948 from Greene's mother to his wife shows that Greene's running away from school was 'much more serious and distressing' than the game of hide-and-seek Greene lightly represents, and that the note he left his parents was more disturbing than he suggests. (He told them he had tried to commit suicide with eyedrops and that they would never seem him again.) Greene's schooldays at Berkhamsted School were the origin of his spy mentality, his fascination with secrecy, betrayal and the hunted man. ('In the lost boyhood of Judas/ Christ was betrayed.') Greene was a son of the headmaster, Charles Greene so the boys were suspicious of him as a possible 'sneak'. A boy called Lionel Car- ter (it is a thousand pities that he died, after a career with the Cable and Wireless Company in Aden, before Sherry could grill him) tormented him, changed him from 'a trusting child into an untrusting man'. Perhaps Sherry does not probe deep enough. In The Lost Childhood (1951) as Sherry points out — Greene compared Carter with the Viper of Milan and wrote of their 'beauty'. When Greene (in Sher- ry's opinion) portrayed Carter as Hilfe in The Ministry of Fear, he wrote of him: 'The face seemed to Rowe very beautiful, more beautiful than his sister's. . .'. The adult Greene is not homosexual, but even the robustly heterosexual Clive James has admitted that he was gay as a goose in adolescence; and possibly Greene's fear of Carter was tinged — consciously or sub- consciously — with some kind of love or hero-worship.

An uncharitable view of Greene's con- version to Roman Catholicism would be that he joined the church for the same reason as Henry VIII left it: to be able to marry the woman he loved; that Greene simply followed the advice of his friend Claud Cockburn — 'Take instruction or whatever balderdash they want you to go through, if you need this for your f---, go ahead and do it, and we both know the whole thing is a bloody nonsense. It's like Central Africa — some witchdoctor says you must do this before you can lay the girl.' It worked like a charm. Vivien Dayrell-Browning, who, as Sherry says, seemed to love Greene's letters 'more than the letter-writer', caved in after his conver- sion. As biographer, Sherry reasonably takes a more sympathetic view of the conversion; though, as so often, he is too ready to accept Greene's own explanation at its face value — that the conversion was the result of 'the emptiness of life in Nottingham [Greene was then a sub-editor on a Nottingham paper] and to his sense of duty towards the woman he hoped to marry'. In talking to Sherry, Claud Cock- burn implied that he thought the conver- sion was a cynical stratagem which had turned into the real thing — 'to my amazement, the whole thing suddenly took off and became serious. . . How far did Greene's conversion really 'take'? Large chunks of his novels could be used as anti-Catholic propaganda; and the Roman Catholic Church has placed some of his books on the Index Librorum Prohibitor- um. In 1974, asked by Sherry whether he was still a Catholic, Greene 'thought he probably was not'.

What goes a long way to convince me that the conversion was, or became, genuine, is that Greene has not committed suicide. Dreams of suicide, failed experi- ments with suicide and fictional suicides splatter the text with their bloodlessness at about 20-page intervals throughout the book. Sherry — probably rightly — be- lieves Greene's stories about his having a shot at Russian roulette, though he scrupu- lously notes that one of Greene's poems in Babbling April (1925) 'suggests that he might not have been in danger' (Greene wrote: 'We make our timorous advances to death, by pulling the trigger of a revolver, which we already know to be empty.') I think Greene early attained a state of mind in which he did not care much whether he lived or died. This attitude confers great power: it means there is little you fear short of Jonathan Miller's pet nightmare of `being tortured for information I don't have'. The belief ascribed to Roman Catholics that suicide is 'the unforgivable sin' may account for Greene's miraculous survival.

Sherry does not grapple strenuously enough with the central contradiction of Greene's life: his becoming a Catholic and his becoming a Communist. 'Arthur Calder-Marshall', Sherry writes, 'felt that as a Catholic convert Greene faced a different quandary [during the Spanish Civil War] than that of Evelyn Waugh whose sympathies lay with Franco, as an enemy of Communism. Greene's sense of right and wrong lay with the Popular Front movement, but as a Catholic he had to side with the Catholics. . .'. What does that mean, in plain English? It means that Greene held — or affected to hold — two irreconcilable philosophies. George Orwell wrote 'I have even thought that he might become our first Catholic fellow-traveller'.

Sherry gives us a curious non-episode of 1935: in spite of urgent deadlines for two books, Greene sent a synopsis of a 10,000- word story, 'Miss Mitton in Moscow', to his agent. He hoped she could persuade the News Chronicle to commission it so that he could leave for Moscow in ten days. Sherry comments: 'It would seem that Greene had an ulterior motive in his haste to get the commission, and depart by ship, within ten days' — and we wonder what is coming. Nothing more sensational than the suggestion that Greene may have been planning a novel, not a short story, based on the purge trials in Moscow. But as Greene already had experience of espion- age in Germany; as he joined the Com- munist Party; and as he was a lifelong friend of Kim Philby, I would at least have wanted to ask: `Were you not tempted to become a Soviet agent?' Perhaps that is one of the questions he declined to answer.

Sherry points up much more clearly the second incongruity in Greene's life. We are surprised to learn that, with all his taste for `seediness', Greene was so ambitious, so clubbable, Establishment, charming, money-conscious, professional. He has been imaginatively opportunist: 'Cheek is victorious!!' he wrote to Vivien in 1926. He showed wishful thinking as well as cheek in 1931 by asking La Compagnie Interna- tionale des Wagons Lits for a free ride on the Orient Express to write a novel about it. The canny Frogs explained that they were forbidden by their charter with the railway companies to give free passes. That was one of the few times his bluff was called. Greene is strong-willed, very deter- mined when he has decided he wants something: What Lola wants, Lola gets.

The fascinating story is not too fascina- tingly told. Sherry has the 'Take It from Here' manner of the university lecturer. He is forever announcing what he is about to tell us, as a conjuror might say: 'I am now going to produce a rabbit from this hat.' So at the best of times, Sherry is a little ponderous; at his worst he is porten- tous, as when recording how Greene's nurse threw a run-over dog into his pram: `Wouldn't there be a growing sense of panic, even nausea, on finding himself shut in, irrevocably committed to sharing the limited confines of a pram with a dead dog?' (Harry Graham might have turned that into one of his Ruthless Rhymes for Heartless Homes: '0 Maud, I wish you wouldn't cram/ A canine corpse into my pram.') Too often Sherry's observations are trite or truisms: 'Graham Greene's mother was naturally to be an important influence in his life.' There is banal and futile speculation: 'One wonders what they found to talk about, with Greene's thoughts no doubt engrossed with what might lie ahead.' And at times Sherry is so puffed up with triumph in his (admittedly admirable) detective discoveries, that he needs only a Belgian accent to sound exactly like Hercule Poirot: 'My belief is that Mr "X" was Hugh Chesterman, a children's novelist long since dead. My own suspicions were first aroused by a note of unexplained acerbity in one of Greene's letters written from Ambervale in which he referred to his young pupil's grandfather.'

But, with all its flaws, this is the book we needed on Graham Greene. An honest, fair and indefatigable researcher has won us the facts. He has done so while Greene, Vivien Greene and many others of the leading figures are around to have their pips squeezed out. Few other writers would have been prepared to dedicate ten or more years of their lives to this work. As Greene's co-religionist Hopkins wrote in `The Windhover': 'Sheer plod makes plough down sillion / Shine.'

Sherry admits that if the biographer's aim is not only to trace the life and career of his subjects, but also 'to penetrate the mystery of his character and personality', then 'there could be few more difficult subjects that Graham Greene'. So far, Sherry has not revealed more than the mask beneath the mask. It is not perhaps incumbent on him to 'sum up' Greene until Volume Two. But then we shall expect answers to the questions that Greene's opacity has provoked. Is he, as Malcolm Muggeridge thinks, 'a saint trying unsuc- cessfully to be a sinner'? Is he, as Lady Diana Cooper opined, 'a good man posses- sed of a devil', as opposed to Evelyn Waugh whom she thought 'a bad man for whom an angel is struggling'? Or is he just, as wise old Noel Coward suggested, some- one who 'like most of God's creatures, aches to be loved'?

1 Bevis Hillier is at work on the second volume of his biography of John Betjeman.

Previous page

Previous page