ARTS

Sculpture

Makonde: Wooden Sculpture from East Africa (Museum of Modern Art, Oxford, till 21 May, and touring)

Out of Africa

Tanya Harrod

Contemporary African artists have dif- ficulty in promoting their work in the West. The great collections concentrate on art made for ritual purposes, squirrelled out of Africa and displayed formally with- out the context of the shrine, dance or the wayside. In this way the objects fit neatly into our notions of modernism and, in the States at least, are often an adjunct to holdings of modern paintings and sculpture from which the contemporary art of Africa is noticeably absent. Yet in this century numerous new art forms have sprung up in African countries — the most naïve often gaining our approval (wire toys, sign paint- ing), whilst others are suspected of tourist or airport art tendencies by arbiters of taste who do not know urban Africa.

Certainly Makonde carvings have their airport forms but the majority of Makonde artists have catered for the consumerism of the First World without losing their artistic integrity. Migrants from the south who moved up into what is now Tanzania, Makonde sculptors early in this century spontaneously began to make pieces that were quite different from the art of their forefathers. The question is — were the Makonde responding solely to the desires of their Western customers by giving them the kind of art which seemed 'African'? The phenomenon is a baffling one. Cer- tainly they abandoned their traditional materials and took to carving in dark hardwood. Europeans preferred its lasting qualities and, absurdly enough, seemed to expect carvings made by Africans to echo the colour of their skin. The carvings deploy both naturalism and the grotesque, both being thought appropriate by First World purchasers. Similarly a Western desire for major art is satisfied by the gigantism of some of these pieces. But on the other hand the Makonde remained completely artistically independent, refus- ing to repeat work or to take exact orders from traders and middlemen.

The fine collection at MoMA (30 Pem- broke Street, Oxford) was brought together in the Fifties and Sixties by a husband-and-wife team — Moti and Kan- chan Malde. Wherever possible they bought direct from the sculptors and were able to record the narratives depicted in the carvings. The sculptures fall into three main groups. The binadamu, literally 'chil- dren of Adam', are naturalistic depictions of local types, the kind of art made to oblige the traveller the world over. Nonetheless binadamu are not toylike or quaint; the Makonde seem incapable of unimaginative carving. In the 1950s an extraordinary new art form was invented: shetani — the depiction of the spirits that

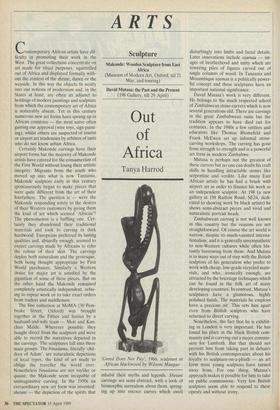

'Greed Does Not Pay', 1966, sculpture in African blackwood by Wilsoni Mangao

inhabit their myths and legends. Shetani carvings are semi-abstract, with a look of biomorphic surrealism about them, spring- ing up into rococo curves which swell disturbingly into limbs and facial details. Later innovations include ujamaa — im- ages of brotherhood and unity which are towering piles of figures carved out of single columns of wood. In Tanzania and Mozambique ujamaa is a politically power- ful concept and these sculptures have an important national significance.

David Mutasa's work is very different. He belongs to the much respected school of Zimbabwean stone-carvers which is now several generations old. There are carvings in the great Zimbabwean ruins but the tradition appears to have died out for centuries. In the 1940s a few settlers and educators like Thomas Blomefeld and Frank McEwen set up informal stone- carving workshops. The carving has gone from strength to strength and is a powerful art form in modern Zimbabwe.

Mutasa is perhaps not the greatest of these carvers but no one can doubt his craft skills in handling intractable stones like serpentine and verdite. Like many East African artists he has had a brush with airport art in order to finance his work as an independent sculptor. At 198 (a new gallery at 198 Railton Road, SE24, dedi- cated to showing work by black artists) he shows semi-abstract pieces and vivid and naturalistic portrait heads.

Zimbabwean carving is not well known in this country but the reasons are not straightforward. Of course the art world is narrow, despite its much-vaunted interna- tionalism, and it is generally unsympathetic to non-Western cultures while often bla- tantly borrowing from them. And Mutasa is in many ways out of step with the British sculptors of his generation who prefer to work with cheap, low-grade recycled mate- rials, and who, ironically enough, are attracted by the bricolage techniques which can be found in the folk art of many developing countries. In contrast, Mutasa's sculptures have a glamorous, highly polished finish. The materials he employs have a precious air. This sets him apart even from British sculptors who have returned to direct carving.

Nonetheless, the fact that he is exhibit- ing in London is very important. He has found his place in the black British com- munity and is carrying out a major commis- sion for Lambeth. But that should not prevent him from taking part in debates with his British contemporaries about his loyalty to sculpture-on-a-plinth — an art form most young sculptors have turned away from. For one thing, Mutasa's approach makes it possible for him to take on public commissions. Very few British sculptors seem able to respond to these openly and without irony.

Previous page

Previous page