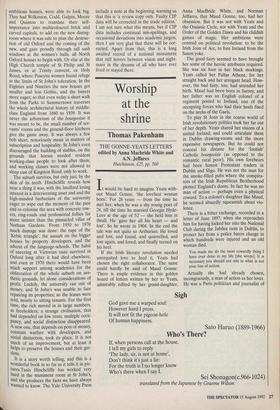

Worship at the shrine

Thomas Pakenham

THE GONNE-YEATS LETTERS edited by Anna Macbride White and A.N. Jeffares Hutchinson, £25, pp. 560 It would be hard to imagine Yeats with- out Maud Gonne, 'the loveliest woman born'. For 28 years — from the time he met her, when he was a shy young poet of 24, till the time he married Georgie Hyde- Lees at the age of 52 — she held him in thrall. He 'gave her all his heart — and lost'. So he wrote in 1904. In the end the tale was not quite so Arthurian. He loved and lost, and found, and quarrelled, and lost again, and loved, and finally turned on his heel.

If the Irish literary revolution needed unrequited love to feed it, Yeats had chosen the right collaborator. The same could hardly be said of Maud Gonne. There is ample evidence in this golden hoard of letters written by her to Yeats, admirably edited by her grand-daughter, Anna MacBride White, and Norman Jeffares, that Maud Gonne, too, had her obsession. But it was not with Yeats and the Ossianic Cycle, nor with Yeats and the Order of the Golden Dawn and his childish games of magic. Her ambitions were centred on political revolution: to be the Irish Joan of Arc, to free Ireland from the Saxon yoke.

The good fairy seemed to have brought her some of the heroic attributes required. She was six foot in her black stockings. Yeats called her Pallas Athene, for her straight back and her arrogant head. How- ever, the bad fairy, too, had attended her birth. Maud had been born in Surrey, and her father was an English colonel of a regiment posted to Ireland, one of the occupying forces who had their heels fixed on the necks of the Gaels.

To play St Joan in the coarse world of Irish revolutionary politics took her far out of her depth. Yeats shared her visions of a united Ireland, and could articulate them in Dublin drawing-rooms and the more expensive newspapers. But he could not conceal his distaste for the 'loutish' Catholic bourgeoisie (as opposed to the romantic rural poor). His own forebears had been honest Protestant traders in Dublin and Sligo. He was not the man for the smoke-filled pubs where the conspira- tors of the Irish Republican Brotherhood plotted England's doom. In fact he was no man of action — perhaps even a physical coward. To a colonel's daughter like Maud, he seemed absurdly squeamish about vio- lence.

There is a bitter exchange, recorded in a letter of June 1897, when she reproaches him for having locked her into the National Club during the Jubilee riots in Dublin, to protect her from a police baton charge in which hundreds were injured and an old woman died.

You made me do the most cowardly thing I have ever done in my life [she wrote]. It is necessary you should not mix in what is not your line of action.

Actually she had already chosen, incongruously, a man of action as her lover. He was a Paris politician and journalist of

Sigh

God gave me a warped soul: However hard I press, It will not fit the pigeon-hole Of human happiness. Sato Haruo (1889-1966)

Who's There?

If, when persons call at the house, I tell my girls to reply 'The lady, sir, is not at home', Don't think it's just a lie: For the truth is I no longer know Who's there when I say I.

Sei Shonagon(c.966-1024)

translated from the Japanese by Graeme Wilson the extreme Right, Lucien Millevoye, who dismissed Irish revolutionaries as mere farceurs. Rumours of this affair, and of the love-child, Iseult, it produced eventually reached Ireland, and did not assist Maud in her self-appointed role as St Joan. In 1900 Millevoye finally threw her over in favour of a young actress in a cafe-chantant. And now there seemed a chance for Yeats (aghast to hear of the affair with Millevoye for the first time, though it had already been going on for 11 years). Maud was prepared to offer him a 'spiritual marriage', and boldly kissed him on the lips. But she was still unable to take Willie seriously as a flesh-and-blood husband. In 1903 she became a Catholic and married someone even more unsuitable than Millevoye.

The man she chose to marry was a reso- lute republican with an outstanding record in fighting the British: John MacBride, the second-in-command of the Irish Brigade that fought on the Transvaal side in the Boer War two years before.Yeats wrote Maud a hysterical letter of protest. He accused her of betraying their ideals by marrying beneath her;

I appeal to you .. . to come back to yourself. To take up the proud solitary haughty life that made you seem one of the Golden Gods.

Within two years the marriage was in the gutter. There was a sordid legal wrangle over the terms of separation, and Maud found herself further isolated from the revolutionary brotherhood she longed to lead. She claimed that MacBride became violent when he was drunk, which he often was, and had made sexual advances to her female relations, including her 10-year-old daughter Iseult. Nationalist Dublin was shocked by the attack on their hero, MacBride. Most people thought Maud Gonne was lying. After all, she was English. (She only claimed an Irish-born great- grandfather, called Gun.) The disaster gave Willie his chance once again. He and his literary friends, Synge and Lady Gregory, befriended Maud. The 'spiritual marriage' was renewed. There may have even been a few reckless nights of physical love thrown in. (The evidence from the bedroom keyhole is inconclusive.) But Willie and Maud were drifting apart.

The excitement of unrequited love is difficult to maintain for 28 years. Yeats gave much of his energy to the newly creat- ed Abbey Theatre. He had also fallen in love with Iseult. In 1917 he proposed to both his Golden Goddess and her daugh- ter, and both rebuffed him. He then married an ordinary mortal — Georgie Hyde-Lees, less than half his age, and with- out any dangerous opinions of her own.

In the Civil War of 1922, Yeats and Maud Gonne found themselves on oppo- site sides. The wounds took long to heal. Had not the loveliest woman born bartered her cornucopia of gifts for an old bellows full of angry wind?

Previous page

Previous page