Exhibitions 2

The Avant-Garde in Catalonia: 1906-1939 (La Pedrera, Barcelona, till 30 September)

Flying the flag

John London

The Olympic Arts Festival is already a fact. You have the programme in your hands. We believe that it has an open and rigorous offer, with a wide range of activi- ties meant for all kinds of spectators. First of all for the Barcelonians, but also for all those who come to this city to experience a big cultural and sporting summer.'

Thus runs the gloriously awkward English version of the publicity booklet for the 'cultural Olympics'. It implies an easy blend of sports and arts. But, could anyone seriously imagine that, after a heavy day watching weight-lifting, hockey and athlet- ics, sometimes in temperatures well over 30 degrees centigrade, sports fans would sud- denly rush off into the centre of the city to see a play by Hrabal, performed in Czech or an absurdist Catalan drama? Besides, nobody is awarded medals for cultural achievement and, as far as 1993 is con- cerned, one thing seems certain: from rid- ing high as the winner of Olympic prestige in 1992, Barcelona will have little left to spend on public services during next year.

Of course, the theory is that the amount of investment attracted to the city will quickly compensate for local government overspending. However, the arts budget is unlikely to be the first beneficiary of any such income. The autumn theatre festival has already been cancelled and museum curators are preparing themselves for a lean priod. So what exactly has been gained in cultural terms?

The most significant answer is related to the desire for an independent linguistic and political identity. Catalan was one of the four official languages of the Olympic Games (the other three being Spanish, French and English). The Catalan flag flew alongside the Spanish flag on most occa- sions. On the day after the grand opening ceremony (in which even King Juan Carlos spoke a bit of Catalan), the Catalan news- paper Avui announced proudly in its front- page headline: 'A Brilliant Beginning to the Games: A Great Spectacle in Which Catalan Symbols Were in Evidence.'

On the same day, in the streets of Barcelona, a radical left-wing Catalan party was selling T-shirts which proclaimed, in Catalan: 'Spain? Get it out of your head!' They depicted a cartoon figure pulling a Spanish flag out of his ear.

International sports events will always generate cultural clashes, even if they are not always so internecine. Outside the sports grounds, the cross-cultural images were more striking. In the Placa de Catalunya regionalist dances were per- formed in the presence of huge, inflatable men. If only the arts could also stimulate sponsorship from manufacturers of US Smarties.

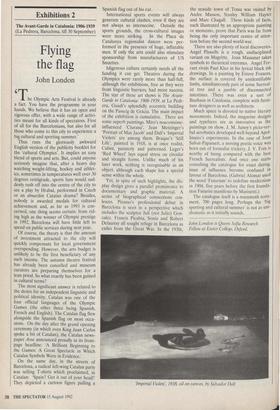

Idigenous culture certainly needs all the funding it can get. Theatres during the Olympics were rarely more than half-full, although the exhibitions, free as they were from linguistic barriers, had more success. The star of these art shows is The Avant- Garde in Catalonia: 1906-1939, at La Pedr- era, Guadf's splendidly eccentric building on the Passeig de Gracia. The main impact of the exhibition is cumulative. There are some superb paintings. Miro's noucentsime- influenced `Ciurana', Jean Metzinger's 'Portrait of Max Jacob' and Dali's 'Imperial Violets' are among them. Braque's 'Still Life', painted in 1918, is at once realist, Cubist, painterly and patterned. Leger's 'Red Wheel' lays equal stress on circular and straight forms. Unlike much of his later work, nothing is recognisable as an object, although each shape has a special sense within the whole.

Yet, in spite of such highlights, the dis- play design gives a parallel prominence to documentary and graphic material. A series of biographical connections coa- lesces. Picasso's professional debut in Barcelona is seen in a perspective which includes the sculptor Juli (not Julio) Gon- zalez. Francis Picabia, Sonia and Robert Delaunay all sought refuge in Barcelona as exiles from the Great War. In the 1930s,

the seaside town of Tossa was visited by Andre Masson, Stanley William Hayter and Marc Chagall. These kinds of facts, each illustrated by an appropriate painting or memento, prove that Paris was far from being the only important centre of atten- tion before the second world war.

There are also plenty of local discoveries. Angel Planells is a rough, undisciplined variant on Magritte. Joan Massanet takes symbols to theatrical extremes. Angel Fer- rant rivals Paul Klee in his lyrical black ink drawings. In a painting by Esteve Frances, the surface is covered by unidentifiable limbs, simultaneously part of some Surreal- ist tree and a jumble of disconnected intestines. There was even a sort of Bauhaus in Catalonia, complete with furni- ture designers as well as architects.

Much space is devoted to native literary movements. Indeed, the magazine designs and typefaces are as innovative as the paintings on show. J. M. Junoy's picto-ver- bal acrobatics developed well beyond Apol- linaire's experiments. In the case of Joan Salvat-Papasseit, a moving poetic voice was born out of formalist trickery. J. V. Foix IS worthy of being compared with the best French Surrealists. And once one starts consulting the catalogue for exact dating, issue of influence become confused in favour of Barcelona. (Gabriel Alomar used the word 'Futurism' to redefine modernism in 1904, five years before the first founda- tion Futurist manifesto by Marinetti.)

The catalogue itself is a mammoth testa- ment, 700 pages long. Perhaps the 'big sporting and cultural summer' is not as uni- diomatic as it initially sounds.

John London is Queen Sofia Research Fellow at Exeter College, Oxford.

'Imperial Violets', 1938, oil on canvas, by Salvador Dali

Previous page

Previous page