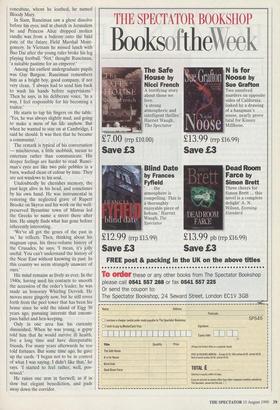

A meeting with Sir Steven Runciman

James Owen

History and Sir Steven Runciman have long walked hand in hand. They have been sweethearts since childhood, but having turned 95 last month, the great his- torian of the Crusades no longer moves in his muse's shadow. He has himself become living history. Few other people remember Asquith in power; no one else has been best friends with George Orwell and Cecil Beaton.

There is very little that Runciman has not seen or sought out. He has played piano duets with the last Emperor of China and read the tarot for the King of Egypt. He has met all but three of the century's prime ministers and mastered ten lan- guages, including classical Armenian. But he carries his learning lightly.

`There is a dangerous word I can never remember,' he says, confessing to an occa- sional confusion of Bulgarian and Russian. `In one language it means matches. In the other,' he continues unexpectedly, 'it means your penis.'

Such is the nature of Runciman's mind. Amused and precise without being donnish, it remains a last repository of Edwardian values, sure of its excellence, yet always keen to increase its reach. As he manoeuvres his lame but still elegant frame into the lift at the Athenaeum, he com- ments on its rectangular shape.

`Do you know why it's like that? It's so that they can bring coffins down when members die in the bedrooms.' And his face, settled by age into that of a saintly tortoise, suddenly beams like a happy schoolboy.

He has always been comfortable with the presence of history. Born in a house next to Hadrian's Wall, he was the second son of Walter Runciman, a member of Asquith's Cabinet and, as Viscount Runciman of Doxford, leader of the mission that per- suaded the Czechs to make concessions to Hitler. Steven's mother was also immersed in politics, being the first wife of an MP to take a seat in the Commons. Steven's par- ents tolerated no slouching in the nursery; by the age of six he could read Latin and Greek.

One of his first memories is of waiting for suffragettes to carry out their vow to break the windows of Cabinet ministers' houses. 'Quite early in the morning, two tough ladies started walking to and fro out- side, carrying bags containing stones and hammers. My sister and I were very excit- ed, so we went out into the street and my sister said, "Please, when are you going to start, as we have to go for our walk and we don't want to miss the fun".' The cam- paigners stalked off in a huff, and the Runcimans' was the only house undamaged that afternoon.

A shy, frail child, in 1916 Steven went to Eton, where the future George Orwell was in the same year. Runciman has always held friendship dear, something that colours his memory of Eric Blair. 'We were very close friends,' he recalls, pointing out that the first item in Orwell's Collected Works is a letter to him. 'But,' he adds, 'he was a curious boy. He didn't really like peo- ple. He liked their intellectual side, some- one to talk to, but friends didn't really mean anything to him.' He pauses, and takes another sip of coffee.

Steven's adolescence was dogged by poor health after he grew seven inches in his first year at school. He was also afflicted by an extreme diffidence that drew a rebuke from Asquith's formidable wife, Margot, whose son Puffin was another good friend of his. 'It's not so much that you've got bad manners,' she told the bashful Runciman, `as no manners at all.'

He did not become gregarious until he got to Cambridge, where he was helped to find his feet by the future residents of Bloomsbury. 'Maynard Keynes was very kind to me,' he says, as if talking about the window-cleaner. Then he whispers, touch- ingly: 'I was terrified of him.'

Runciman soon became something of an aesthete and his rooms at Trinity housed a large green parakeet named Benedict and another beautiful young man, Cecil Beat- on. He used Runciman as his first photo- graphic model outside his family, and later remembered the shoot in his Photobiogra- phy. 'When I photographed Steven . . .

with a budgerigar poised on his ringed fin- ger, looking obliquely into the camera in • the manner of the Italian primitives, I knew I had not lived in vain.'

Although Runciman and Beaton remained in touch, they went their separate ways as Runciman sought an academic career. 'His social ambitions were far above mine,' he recalls affectionately. Then his voice sinks conspiratorially. 'He was really rather annoyed when I got a knighthood long before he did.'

Runciman's liking for Greece, and his romantic conception of the Middle Ages, led him naturally to the study of Byzantium. When he began his researches in the 1920s, scholars, taking their cue from Gibbon, damned the Later Roman empire as an effete culture unworthy of study. It was an attitude transformed by Runciman's prodigious work over the next 50 years, and he is largely responsible for the blossoming of Byzantine studies in Britain.

He made his approach to history clear from the start. In his first book, a study of the 10th-century emperor Romanus Lecapenus, Runciman rejected narrow analysis in favour of grand narrative, emphasising the importance for his period of the lives of the mighty. 'History, after all,' he wrote in 1929, 'is only a mosaic of biographies, and some stones are large and affect the whole design.'

His view of his task has changed little in 70 years. 'I think the job of the historian is to make history readable,' he says, 'which most historians are not very good at. It has become too much the province of academics, who write only to impress their contemporaries.' His own writing style is admirably lucid, composed with a simplicity and dispassion that would have won the, approval of Byzantine icono- graphers. A delicate humour is also present. No other- historian could have written the sentence, 'This is not the place to discuss the psychological results of castration.'

Runciman used the Cambridge holidays to' see much of the world before it sub- scribed to a uniform culture. When his early researches were interrupted by pleurisy, he recuperated by sailing to China. There he was summoned to play the piano with Henry Pu Yi, the ex-Emperor, who told him he had chosen his forename out of fondness for the Tudors. His chief concubine, whom he loathed, he named Bloody Mary.

In Siam, Runciman saw a ghost dissolve before his eyes, and at church in Jerusalem he and Princess Alice dropped molten candle wax from a balcony onto the bald pate of the future Field Marshal Mont- gomery. In Vietnam he missed lunch with Bao Dai after the young ruler broke his leg playing football. 'Not,' thought Runciman, 'a suitable pastime for an emperor.'

Among his earliest undergraduate pupils was Guy Burgess. Runciman remembers him as a bright boy, good company, if not very clean. 'I always had to send him back to wash his hands before supervisions.' Then he says, in his deliberate voice, 'In a way, I feel responsible for his becoming a traitor.'

He starts to tap his fingers on the table. `Yes, he was always slightly mad, and going to make a mess of his life anyhow. But when he wanted to stay on at Cambridge, I said he should. It was then that he became a communist.'

The remark is typical of his conversation — mischievous, a little snobbish, meant to entertain rather than communicate. His deeper feelings are harder to read. Runci- man's eyes are like two pale pebbles in a burn, washed clean of colour by time. They are not windows to his soul.

Undoubtedly he cherishes memory, the past kept alive in his head, and sometimes by his own hand. He was instrumental in restoring the neglected grave of Rupert Brooke on Skyros and his work on the well- preserved Byzantine town of Mistras led the Greeks to name a street there after him. He simply finds what has gone before inherently interesting.

`We've all got the genes of the past in us,' he reflects. Then, thinking about his magnum opus, his three-volume history of the Crusades, he says, 'I mean, it's jolly useful. You can't understand the history of the Near East without knowing its past. In this country we seem strangely unaware of ours.'

His mind remains as lively as ever. In the 1940s, having used his contacts to smooth the accession of the order's leader, he was made an honorary Whirling Dervish. He moves more gingerly now, but he still roves forth from the peel tower that has been his home since he sold the island of Eigg 30 years ago, pursuing interests that encom- pass ballet and hen-keeping.

Only in one area has his curiosity diminished. When he was young, a gypsy told him that he would survive ill health, live a long time and have disreputable friends. For many years afterwards he too told fortunes. But some time ago, he gave up the cards. 'I began not to be in control of what I was saying. I didn't like that,' he says. 'I started to feel rather, well, pos- sessed.'

He raises one arm in farewell, as if in slow but elegant benediction, and pads away down the corridor.

Previous page

Previous page