Exhibitions 3

Along the Golden Road to Samarkand: Photographs of Monuments in the Middle East by A.W. Lawrence, T.E. Lawrence and Robert Byron (Courtauld Institute, till 1 March)

Tombs with a view

James Knox

Robert Byron taught himself the art of photographing buildings in the difficult light of India, using a wide-lensed camera bought in Calcutta. His talent became immediately apparent on publication in 1931 of his definitive survey of Lutyens's recently completed Viceroy's Palace in New Delhi in a special issue of the Archi- tectural Review. Numerous commissions fol- lowed from both the Architectural Review and Country Life and by the time he set off on his search for the roots of Islamic archi- tecture which took him on his great journey through Persia and Afghanistan in 1933-34 he had become an architectural critic and photographer of note.

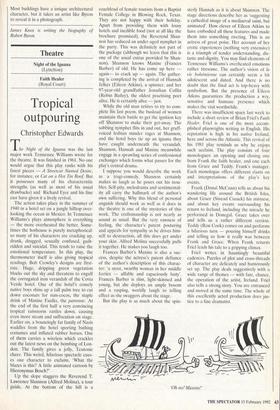

Byron described his adventures and dis- coveries made on the journey in his master- piece, The Road to Oxiana. Written in diary form, its informal style belies the scholar- ship and taste which guided him on his travels. Apart from keeping a detailed diary filled with notes and sketches he also took over 1,000 photographs, and this material furnished his important study of Timurid architecture which appeared in truncated form in A Survey of Persian Art, published in 1938. His collection of pho- tographs is now in the Conway Library of the Courtauld Institute. Some were donat- ed by Byron himself in 1938 and the remainder by his mother in 1947 after Byron's death during the war. A small group of his photographs was exhibited in Tehran in the 1970s but the current exhibition provides the first oppor- tunity to study Byron's photographs in England since the war. Byron understood the power of the camera to influence the course of taste, for he himself was first drawn to Central Asia by a photograph, published by the German scholar Diez, of the extraordinary tomb tower at Gunbad-i- Qabus on the Turkoman steppes. Unlike Diez's close-up, Byron conveyed the myste- rious power of this and other tomb towers by setting them in panoramic views of the desolate winter landscape of the steppe.

The teacher in Byron took photographs which illustrate the engineering of build- ings; he relished details of semi-ruined vaults and domes which revealed the inge- nious stalactite construction behind. The aesthete produced close-ups of exquisite stucco decoration of late Mongol mihrabs, discriminating against the much later paint- ed decoration of the Safavids. And the crit- ic emphasised the composition and mass of the monuments, showing their kinship, found in all great architecture, to sculpture. On the scrubby plains and in the ruined cities of Persia and Afghanistan Byron found his ideal buildings. In photographing them he resolutely turned his hack on pic- turesque composition, and his unsentimen- tal approach presents a brilliant case for the architecture of the Seljuk, Mongol and Timurid dynasties to be considered some of the greatest in the world.

It is a miracle any of these photographs survived at all. Before leaving Tehran for the final leg of his journey to Kabul, Byron, as usual in a great rush, packed his films into a box addressed to his father with nothing more than `Savernake Station, GWR'. This turned out to be safer 'than carrying them with him. A few days later on the road to Meshed Byron's car collided with a lorry and his luggage, including all his unused film, was crushed under its wheels. This exhibition is good reason to give thanks that they survived. Much of what he photographed in Afghanistan and at Herat in particular has now been destroyed by earthquakes and Russian bombs. Herat had been the capital of the Timurid Empire for most of the 15th cen- tury but its inaccessibility had led to its neglect by travellers and scholars. Byron was one of the first British travellers this century to study and record the surviving fragments of arguably the greatest period of Islamic architecture.

Arriving in Herat at night in November 1933, Byron had the impression of seeing a dense group of factory chimneys; then he saw the silhouette of a broken dome and realised that what he had seen were minarets. Today, the two of greatest artistic importance have been demolished and Byron's photograph of one of them (no 11 in the exhibition) is devastating evidence of what we have lost.

If you need further proof of Byron's gifts as photographer look at the handful of prints by T.E. Lawrence also in this exhibi- tion. The great basalt fort of Azraq where Lawrence hid from the Turks is reduced in his photograph to a featureless ruin and the charming Ottoman architecture of Jidda has the appearance of a backdrop.

Photograph by Robert Byron of the funerary tower, 1007, at Gunbad-i-Qabus on the Turko- man steppes, taken on his journey through Persia and Afghanistan in 1933-34

Most buildings have a Unique architectural character, but it takes an artist like Byron to reveal it in a photograph.

James Knox is writing the biography of Robert Byron.

Previous page

Previous page