CHESS

It is one of the mysteries of chess that India, the most likely birthplace of the game, has produced so few masters of the art. In the 19th century there was the Brahmin Moheshunder Bonnerjee, who contested some interesting games with Cochrane in Calcutta. But it is not until the advent of Sultan Khan in the late 1920s that one can speak in terms of a true Indian grandmaster. Sultan Khan arrived in Lon- don as part of the retinue of an Indian nobleman, Sir Umar Hayat Khan, ADC to King George V. Master and servant were, in spite of the identity of their last names, obviously not related.

While in London (which he detested because of the weather) Sultan Khan annihilated the best British masters, won the British championship and ended up being promoted to top board of the British Empire team in the chess olympics. During the course of this triumphal career he inflicted defeat on Capablanca, Flohr, Tartakower and other recognised grand- masters. But after six years at the top Sir Umar whisked him back to India and Sultan Khan never again played a top-class chess game. The whole Sultan Khan epi- sode is simultaneously glorious and tragic. Had he stayed at his last Sultan Khan might have become world champion.

For decades India languished with no prospect of another champion, but all this has recently changed with the comet-like progress of Viswanathan Anand, the only player in the world who is regularly able to defeat both Karpov and Kasparov. This week I analyse one of Sultan Khan's games, next week one of Anand's.

Sultan Khan —. Rubinstein: Prague Olympiad, 1931; Stonewall Attack.

1 d4 d5 2 Nf3 c5 3 e3 e6 4 Ne5 Nf6 5 Nd2 Nbd7 6

Indian empire

Raymond Keene

f4 Bd6 7 c3 b6 8 Bd3 Bbl 9 Qf3 h5 10 Qg3

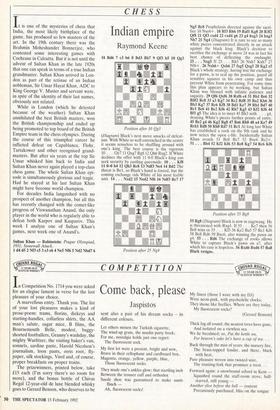

Position after 10 Qg3 (Diagram) Black's next move smacks of defeat- ism. With White so well entrenched in the centre it seems senseless to be shuffling around with one's king. The best course is the vigorous

10 . . . Qe7 11 Qxg7 Rg8 12 Qh6 Rxg2. If White declines the offer with 11 0-0 Black's king can seek security by castling queenside. 10 . . . Kf8 11 0-0 h4 12 Qh3 Rc8 13 Ndf3 Ne4 14 Bd2 The threat is Bel, so Black's hand is forced, but the coming exchange rids White of his most feeble unit. 14 . . . Nxd2 15 Nxd2 Nf6 16 Ndf3 Rc7 17

Position after 25 Ng4

Ng5 Bc8 Prophylaxis directed against the sacri- fice 18 Nxe6+. 18 Rf3 Rh6 19 Rafl Kg8 20 R3f2 Q18 21 Qf3 cxd4 22 cxd4 g6 23 g4 hxg3 24 hxg3 Nh7 25 Ng4 (Diagram) It is rare to see so many white pieces concentrated directly in an attack against the black king. Black's decision to sacrifice the exchange at move 24 was in fact his best chance of deflecting the onslaught. 25 . . . NxgS If 25 . . . Rh5 26 Nxh7 Kxh7 27 Nf6+. 26 Nxh6+ Qxh6 27 fxg5 Qxg5 28 Kg2 e5 Black's whole strategy, having lost the exchange for a pawn, is to seal up the position, guard all sensitive squares in his own camp and thus prevent White from penetrating. For some time this plan appears to be working, but Sultan Khan was blessed with infinite patience and sagacity. 29 Qf6 Qxf6 30 Rxf6 e4 31 Bbl Be6 32 R6f2 Rc8 33 a3 Kg7 34 Rc2 Rd8 35 Ba2 Kh6 36 Bb3 Kg7 37 Rc6 Kf8 38 Bdl Ke7 39 Rhl Bd7 40 Rcl Be6 41 Be2 Kf6 42 Rh7 Kg5 43 Kf2 Kf6 44 Bn g5 The idea is to meet 45 Bh3 with . . . g4, denying White's pieces further points of entry. 45 Be2 g4 46 Kg2 Rg8 47 Ba6 Rb8 48 a4 Ke7 49 Rchl Rd8 50 Rh8 Rd7 51 Rcl At long last White has established a rook on the 8th rank and he now seizes the open c-file. Incidentally Sultan Khan avoids 51 Bc8 Rc7 52 Bxe6 Rc2+. 51 . . . Bb4 52 Kf2 Kf6 53 Re8 Kg7 54 Rc6 Kf6

Position after 55 Rg8

55 Rg8 (Diagram) Black is now in zugzwang. He is threatened with Rxg4. If 55 . . . Ke7 then 56 Bc8 wins or 55 . . . Kf5 56 Keg Ba5 57 Rcl Kf6 58 Bc8 Rd6 59 Bxe6, also winning the pawn on g4. 55 . . . Rd6 The exchange of rooks allows White to capture Black's pawn on a7, after which his case is hopeless. 56 Rxd6 Bxd6 57 Ra8 Black resigns.

Previous page

Previous page