Exhibitions 2

Alma-Tadema (Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, till 2 March; Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool, from 21 March to 8 June)

Glimpse into the ancient world

Martin Bailey

Ama-Tadema's pictures of Roman maidens in diaphanous robes idling on marble terraces have long been dismissed as 'chocolate-box' art. Although one of the most successful Victorian painters, the rep- utation of this most distinctive of artists was to plummet after his death. Alma- Tadema was then ignored by the art world, and only in the early cinema did his influ- ence linger on. The crowd scenes, dress, architecture and atmosphere of his paint- ings inspired a series of films from The Last Days of Pompeii to Cecil B. DeMille's Cleopatra. The exhibition in Amsterdam, which moves to Liverpool in March, is an Anglo- Dutch venture which sets out to resurrect Alma-Tadema's standing as a major Victo- rian artist. Born in a small village in Fries- land in 1836, he was christened Lourens Alma Tadema (legend has it that he later hyphenated his middle and last names so he would come first in art catalogues). After training at the Academy in Antwerp, he married in 1863 and it was on his honey- moon that he developed an infatuation for Roman civilisation. Alma-Tadema toured Italy for two months with his French bride, visiting Florence, Rome and Naples. Above all, it was Pompeii which proved a revela- tion, stimulating his imagination. From then on, he would depict the Classical world.

Sadly, Alma-Tadema's young wife died six years later, and he then moved to Lon- don, explaining that this was 'the only place where my work has found buyers'. In Britain, there was a growing fascination with the extravagance and decadence of ancient Rome, and the artist's images of a golden past were eagerly sought as an attractive escape from the problems of modern society. Alma-Tadema became an almost instant success. He Anglicised his first name, married a 17-year-old English art student, and was soon accepted into the highest social circles. His house and studio in St John's Wood were later decorated like a Pompeiian palace and invitations to his lavish parties were avidly sought. He was knighted by Queen Victoria, ending up with a title and the lyrical name of Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema.

On his death in 1912 he was honoured with a funeral in St Paul's and a memorial retrospective at the Royal Academy. Alma- Tadema then almost immediately fell from grace, although interest in his work has been reawakened since the 1970s, when Victorian art started to become fashionable again.

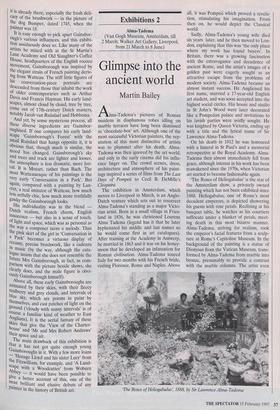

`The Roses of Heliogabalus' is the star of the Amsterdam show, a privately owned painting which has not been exhibited since 1888. Heliogabalus, one of Rome's most decadent emperors, is depicted showering his guests with rose petals. Reclining at his banquet table, he watches as his courtiers suffocate under a blanket of petals, meet- ing death in this most bizarre manner. Alma-Tadema, striving for realism, took the emperor's facial features from a sculp- ture at Rome's Capitoline Museum. In the background of the painting is a statue of Dionysus from the Vatican Museum, trans- formed by Alma-Tadema from marble into bronze, presumably to provide a contrast with the marble columns. The artist even The Roses of Heliogabalus', 1888, by Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema had roses shipped over from the French Riviera during the winter months to pro- vide a constant supply of petals — a sign of both his attention to detail and his wealth.

The other coup of the Amsterdam show is to bring together two masterpieces which were last seen as a pair in 1913. 'The Sculp- ture Gallery' (Hood Museum, New Hamp- shire) and 'The Picture Gallery' (Towneley Hall Art Gallery, Burnley), each seven-foot high, depict two groups of Roman connois- seurs inspecting the latest artworks on sale. In 'The Sculpture Gallery', the works shown are copied from surviving Classical pieces, although Alma-Tadema has used artistic licence to select items from differ- ent periods and places. The family in Roman garb intently admiring a large bronze are his own, with Alma-Tadema in the centre of the composition, an arm pro- tectively outstretched towards his wife and two young daughters.

In 'The Picture Gallery', Alma-Tadema modelled the faces of the toga-dressed con- noisseurs on his successful dealer Ernest Gambart and five other gallery-owners. On the walls, Alma-Tadema has depicted paintings which are based on long-lost works described in Classical literature. But, despite his prodigious efforts to capture the atmosphere of the ancient world, the paint- ings on the walls of 'The Picture Gallery' are densely hung, in the Victorian style.

One of the surprises in the Amsterdam exhibition is an intriguing selection from Alma-Tadema's photographic collection. He assembled over 5,000 professionally- shot photos, some dating back to the 1850s. Most are of antiquities of the Classical world, particularly architectural remains and sculptures. Alma-Tadema carefully sorted these into portfolios by subject mat- ter, using the photos as raw material for objects in his paintings. Although Alma- Tadema used photographs to help create realism in his compositions, he was quite willing to alter an object to make it more appropriate for his painting.

On seeing Alma-Tadema's paintings brought together, his technical skill is evi- dent. In his own day, he was renowned for the way he painted marble, rendering the translucent sheen of its surface. He was once described as a `marbellous' painter, and buyers would usually insist that there a marble object included somewhere in a pic- ture. Yet, despite his skill, Alma-Tadema seems too slick and theatrical to our eyes, too Hollywood. It comes as little surprise in going round the exhibition to find that the owner of 'The Siesta' — a slave girl playing a lute for two reclining men — is recorded as 'J. Nicholson, Beverly Hills, California'.

But whether it is high art or popular entertainment, the exhibition coming to Liverpool provides a fascinating view of the Victorian rediscovery of Classical civilisa- tion. The show is a pleasurable glimpse into the ancient world, a reflection of Alma-Tadema's personal motto: 'As the sun colours flowers, so art colours life.'

Previous page

Previous page