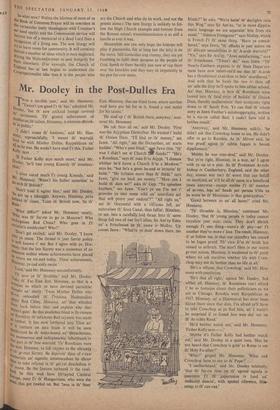

The Churches

Reforming the Reformed

By MONICA FURLONG EvEtt since Dr. Stockwood plunged into the bushes at Carshalton, Anglicans have been reacting like the aunt in The Golden Age, when the curate had heard burglars in the shrubbery and was determined to go and investigate, `Mr. tiodgitts, you are brave! For my sake do not be rash!' It is no secret that the Church of England has been hearing noises in its shrubbery for years; the swish of copes. the clash of thuribles, the echo °f a Kyrie or two. Nor is this all. At other times 4 sad, schizophrenic face has been seen peering through the brandhes, hoarsely crying `No PIPery !' or ,.,'Diiwn with Romista lioctrine!' until 4°Ine of us are utterly bewildered. It was high time someone went to investigiite. Mervyn Stockwood, less biddable than most curates, rush'ed in: wielding the sharp end of his crozier and'knocking down AngloLCatholics left and right. (It is only fair.to mention, though, that his primary intention was to rebuke a naughty curate whoa refused to do what his Rector told him,) Other bishops, less rash or less brave than Southwark, contented themselves with asking, or IniPloring (burnot so far ordering)their clergy t0 Stand loyal to the Prayer Book of 1662 for the time being. For ,while.--eryone agrees that changes are •neeessary it is important to have mutual ground from which to start. To borrow huge gobbets of the Roman missal and translate .1 `1.-41 into English as the extremist Anglo- Catholics do is to sell the ecclesia anglicana up the river.

Liturgical refOrm is in the air : one can smell it unmistakably in the pew, at parish meetings, in the theological colleges, at conferences of clergy, and in private argument with one's friends. Whethq,we like it or not the Book of Common Prayer is bursting asunder at the seams, unable any longer to contain the theological and social changeSof the past 400 years. This generation of Anglicans, gathering its dazed wits together, has realised that to it has fallen the task of continuing, seane say completing, the task the Reformers began: Surprisingly it is warming to the task, and re- examining old truths with a tremulous excitement. (I loved the question Bishop Stephen Neill threw at the Bishop of Salisbury at the last Lambeth Conference, one entirely worthy of the original Reformers. 'Have youTgot a clear,answer, in rela- tion to the Eucharistic sacrifice, to the question "Who offers what to whom'?" 'Poor Dr. Lunt could only hang his . head and shamefacedly answer `No'). After yearsof intellectual conserva- tism the Church of England is in a radical mood, alight with liturgical fervour. it is not simply a matter of re-writing the Prayer Book, but of re- discovering the spontaneity of worship, and of discovering that 'liturgy' means, literally, 'the work of the Church.' Not only its work either; its self-expression, its drama, its passion, its art. its preoccupation, its obsession, its one true love. Clergy have been saying this for years, of course, and now all of a sudden they have been astounded to discover that it is true, that in fact the services of the Church are not the sterile endurance tests they used to seem. Now the problem is to translate the knowledge into a practical form.

In all this the Church of England has been influenced more than perhaps it quite realises by the originality of the Roman Catholic worker- priests. In the spiritual doldrums after the war many young Anglicans, sickened by the bourgeois respectability of their religion, soaked themselves in the writing of the Left-wing French Catholics. Suhard and the Mission to Paris, Godin and Perrin, Jacists and Jocists, became names as familiar to them as Matins and Evensong. Much of what they read they later forgot, but at least one memory stayed to haunt them. When the worker-priests wanted to celebrate Mass they often had no church in which to do so, no altar, no candles, no server, no trained congregation. They borrowed the kitchen of a fellow-worker and temporarily used the table as an altar, blessing a loaf of household bread and breaking it,consecrat- ing a bottle of vin ordinaire for their extraordinary purpose. It was everyday life which was offered on this crudest of altars, and offered so superbly that for a few moments everyone present under- stood who was offering what to whom.

The importance of this offering has now become buried so deep in the Anglican consciousness that since the war nine churches out of ten have made the Eucharist the central service of their Sunday (pushing to one side the intrusive Matins), and many have instituted daily celebrations. But it has gone much farther than that. Enthusiasm is such that now, all over the country, with and with- out the approval of their diocesan bishop, clergy and people are briskly experimenting as they have not done for years, leafing through the early Christian centuries in the search for new ideas and more dramatic methods of expression.

('1 say, listen to this. . . "On the pavement outside the church the paschal fire is started and the great paschal candle lit. The deacon carries it into the darkened church in procession, stopping three times in the midst of the people to cry The light of Christ,' to which the people reply 'Thanks be to God.' Now begins the lighting of the people's candles with the fire of the paschal candle until the church is ablaze with light." Why don't we try that next Easter?')

Many of the laity have, for the first time in their lives, received their Communion from a table in the nave (where they can see what the celebrant is up to), or taken part in an offertory procession. carrying a loaf of bread for consecration (gastro- nomically as well as symbolically an improvement on the usual asbestos disks), or received their Communion in the evening, or eaten a meal after their Communion with their fellow-communi- cants. Candidates for baptism have been received by the whole community of local Christians as in the very early days of the Church, instead of being smuggled in surreptitiously on Sunday afternoons. Experiment is shooting wherever it can find a crevice and a millimetre of soil, and not even the reactionary old ladies can quite manage to weed it out.

So what now? Within the lifetime of most of us the Book of Common Prayer will be rewritten in the vernacular (only theologians with Cranmer's ear need apply) and the Communion service will become less of a memorial to a dead Lord than a recognition of a living one. The new liturgy will try to leave room for spontaneity. It will certainly Include a number of ideas which it once neglected, driving ing the Nonconformists to seek hungrily for them elsewhere. (For example, the Church of England has at last begun to understand the Congregationalist idea that it is the people who are the Church and who do its work, and not the priests alone.) The new liturgy is unlikely to fol- low the High Church example and borrow from the Roman missal; transubstantiation is as stiff a hurdle as ever it was.

Meanwhile one can only hope the bishops will play it pianissimo, for at long last the laity is on the move. Self-conscious and clumsy, they are yet fumbling to fulfil their purpose as the people of God. Speak to them harshly just now or rap them over the knuckles and they may sit impotently in the pew for ever more.

Previous page

Previous page