BBC

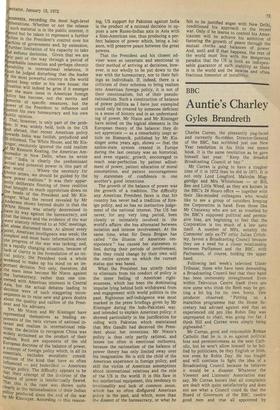

Auntie's Charley

Gyles Brandreth

Charles Curran, the pleasantly pug-faced and currently flu-ridden Director-General of the BBC, has scribbled just one New Year resolution in his little red memo book. It is the same resolution as he gave himself last year: "Keep the dreaded Broadcasting Council at bay."

Mr Curran is going to have a tougher time of it in 1972 than he did in 1971. It is not only Lord Longford, Malcolm Muggeridge and Mrs Whitehouse — or Bill, Ben and Little Weed, as they are known in the BBC's 24 Hours office — together with their like-minded colleagues who would like to see a group of outsiders keeping the Corporation in hand. Even those like Mr Chataway who are not so troubled by the BBC's supposed political and permissive bias, are beginning to feel that the Corporation is too much of a law unto itself. A number of MPs, notably the Commons' only ex-TV critic Julian Critchley, favour a Broadcasting Council because they see a need for a closer relationship between Parliament and the BBC, with Parliament, of course, holding the upper hand.

Following last week's televised Ulster Tribunal, those who have been demanding a Broadcasting Council feel that their hand has been immensely strengthened. Even within Television Centre itself there are now some who think the Beeb may be getting a bit big for its own boots. One producer observed: "Putting on a marathon programme that the Home Secretary had advised against and that an experienced old pro like Robin Day was unprepared to chair, was going too far. I think Hill and Curran were simply being pigheaded." Mr Curran, good and responsible Roman Catholic that he is, is as against political bias and permissiveness as the next Catholic, but he won't allow himself to be bullied by politicians, be they English or Irish, nor even by Robin Day. He has fought and will continue to fight the idea of a Broadcasting Council because he believes it would be a disaster. Whatever the Viewers' and Listeners' Association may say, Mr Curran knows that all complaints are dealt with quite satisfactorily and does not see what a Council could do that the Board of Governors of the BBC, twelve good men and true all appointed by the Queen and Council, cannot do already.

Unfortunately for Mr Curran, he helped to invalidate his own case last October by setting up a complaints tribunal composed of three venerable, if somewhat ancient, former public servants, none of them very eager telly watchers. "What can a complaints tribunal do that the Governors can't do?" Mr Curran would doubtless have asked had anyone put the idea up to him a year before. In answer to that question Mr Curran is now said to be saying in private, "Nothing much." As Sir Hugh Greene, never slow to remind us of his own glorious days as DG, was quick to point out, the hapless trio of distinguished senior citizens were recruited in a " shortsighted attempt to appease those in and out of politics who have been calling for the establishment of a Broadcasting Council." The Independent Television Authority, which actually receives no more than eight or ten letters of complaint a week, set up its own complaints review board with the same aim in view.

Lord Parker, Lord Maybray-King and Sir Edmund Compton got down to work for the first time the other day, but nobody really expects very much of them. After all, their tribunal is a BBC body, set up by the BBC and only able to move into action once the BBC's own internal investigation has taken place and the complainant is still not satisfied. It has no legal status and can do little more than occasionally wave its three fingers at the BBC in admonishment. No one in the BBC intends it to do more.

Despite the Board of Governors, the Three Wise Men and the programme Talkback, in which members of the public can hurl abuse at individual programme-makers who sit defending themselves with wan smiles on tired faces, the Corporation remains open to the criticism that it is, in fact, answerable to no one. Mr Faulkner and Mr Maudling may moan about the Ulster programme and the BBC's coverage of the Northern Ireland situation in general, but they can do nothing to make the Corporation listen to them. As Mrs Whitehouse would say, sitting in the automatically revolving glasshouse her latest book has bought her, "You can tell the BBC you don't like Yesterday's Men or Casanova or Play for Today, but what can you do if the BBC then chooses to ignore you?" Very little, which is just how the producers like it.

At a Christmas cocktail party Charles Curran was heard to rebuke a man for including "three concealed premises in one statement." He is that kind of man, which is why attack is his favourite form of defence. And the line of attack with which he is now going to back up his New Year resolution is to demand a full public inquiry into the future of broadcasting. So far he has promoted the idea only privately, but he can be expected to pronounce on it publicly before long. "He's so keen to get this public inquiry," one producer told me, "that I wouldn't be surprised if he had persisted with the Ulster programme in part because he thought it might precipitate it."

With both BBC and ITA charters coming up for renewal in 1976, Mr Curran may well get his way. Of course, he does not want or expect an inquiry that will suggest anything revolutionary. He believes a public inquiry could only vindicate the BBC and applaud the way it already keeps its house in order, and that's the real reason why he wants one. Mr Curran is optimistic as well as resolute.

Previous page

Previous page