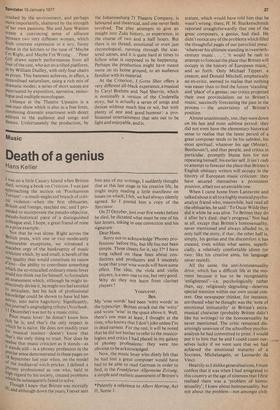

Death of a genius

Hans Keller

1 Was on a little Canary Island when Britten died, writing a book on Criticism. I was just APproaching the section on Posthumous Torture _a much-neglected branch of critical violence—when the first obituaries. British and foreign, reached me; and I proceeded to incorporate the pseudo-objective, Pseudo-historical piece of a distinguished colleague and. I hope, a great friend of mine as a prize example.

Not that he was alone. Right across the aritish press, with one or two moderately honourable exceptions, we witnessed a Macabre orgy of the bankruptcy of music criticism which, by and small, is bereft of the One quality that would constitute its raison cr etre—the ability to contribute something Which the so-miscalled ordinary music lover could not think out for himself, to formulate an assessment which, although he might instinctively divine it, he might not feel entitled tO articulate, lest his lack of professional knowledge could be shown to have led him astray, into naive hagiolatry. Significantly, thisjournal's ungrudging tribute (Notebook, 11 December) was not by a music critic. Poor music lover: he doesn't know how rich he is, and that's the only respect in ,which he is naive. He does not readily trust IS musical instinct—doesn't know that that's the only thing to trust. Nor does he 1..ealise that music criticism as it stands—as it stands still—is a phoney profession in the Precise sense demonstrated in these pages on 18 September last year when, on the model Of mediaeval witch-pricker, I defined a honey professional as one who, held in Igh regard by his society, created problems which he subsequently failed to solve.

h, T ough I knew that Britten was mortally and although down the years, [never sent him any of my writings, I suddenly thought that at this last stage in his creative life, he might enjoy reading a little manifesto on issues on which, I felt, we had always silently agreed. So I posted him a copy of the Spectator.

On 27 October, just over five weeks before he died, he dictated what must be one of his last letters, inking in one correction and his signature : Dear Hans, Sorry not to acknowledge 'Phoney pro fessions' before this, but life has not been simple. Three cheers for it, say I !* I have long talked on these lines about conductors and producers and I sincerely hope that your wise words will have some effect. The idea, the viola and violin players, is a new one to me, but very good. Why do they not learn from clarinet players?

Yours ever, Ben.

My 'wise words' had been 'witty words' in the typescript : Britten struck out the 'witty' and wrote 'wise' in the space above it. Well, there's one man at least, I thought at the time, who knows that I don't joke unless I'm in dead earnest. For the rest, it will be noted that he did not bother to refer to the musicologists and critics I had placed in my galaxy of phoney professions: they were too obvious to be acknowledged.

Now, the music lover who dimly felt that he had lost a great composer would have had to be able to read German in order to find, in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, a simple and realistic assessment of Britten's

stature, which would have told him that he wasn't wrong: there, H. H. Stuckenschmidt reported straightforwardly that one of the great composers, a genius, had died. He didn't notice any of the problems which filled the thoughtful pages of our parochial press: 'whatever his ultimate standing in twentiethcentury music . . 'it would be rash to attempt to forecast the place that Britten will occupy in the history of European music,' and so forth. Only Michael Tippett, a creator, and Donald Mitchell, emphatically an ex-critic, seemed to realise that nothing was easier than to find the future 'standing' and 'place' of a genius; our critics projected their own provincialism on to Britten's music, succinctly forecasting the past in the process — the uncertainty of Britten's position.

Almost unanimously, too, they were down on his last and most sublime period they did not even have the elementary historical sense to realise that the latest period of a great composer tends to be his subtlest, his most spiritual, whatever his age (Mozart, Beethoven!), and that people, and critics in particular, promptly blame him for not repeating himself, his earlier self. It isn't rash to attempt to forecast the place that Britten's English obituary writers will occupy in the history of European music criticism : they have secured themselves a prominent position, albeit not an enviable one.

When I came home from Lanzarote and talked about it all to a highly musical psychoanalyst friend who, meanwhile, had read all the obituaries, he said: `To Oscar Wilde they did it while he was alive. To Britten they do it after he's died: that's progress.' Not bad at all, except that Britten's homosexuality, never mentioned and always alluded to, is only half the story, if that ; the other half is, simply, his genius and the discomfort it has created, even within what seems, superficially, a relatively comfortable idiom (or two : like his creative aims, his language never rested).

All the same, the anti-homosexuality drive, which has a difficult life at the moment because it has to be recognisably 'enlightened'—i.e. psychologically rather than, say, religiously degrading—deserves special mention within our own social context. One newspaper thinker, for instance, attributed what he thought was the 'note of emotional immaturity' in Britten's extramusical character (probably Britten didn't like his writings) to the homosexuality he never mentioned. The critic remained disarmingly unaware of the schoolboy psychoanalysis he had committed to print : I would put it to him that he and I could count ourselves lucky if we were sure that we had achieved the emotional maturity of a Socrates, Michelangelo, or Leonardo da Vinci.

Heartily as I dislike generalisations, I must confess that it was when I had emigrated to this country at the age of nineteen that I first realised there was a 'problem of homosexuality': I knew about homosexuality, but not about the problem—not amongst civit

ised people, one's own kind, anyhow. The intervening decades have not weakened my amazement : to me it seems that there is far more iN-repressed homosexuality in the cultured part of our culture than in any other comparable cultural context I have been in touch with. The result is that however much the laws of the country may have improved, the British homosexual can scarcely escape the role of a scapegoat, even after he has escaped into death : the more substantial his mind, the worse his fate. Only if he is a proper nobody can he hope to be unreservedly esteemed (i.e. amiably ignored) in our permissive or post-permissive society.

As for the bigger half of the story, this egalitarian age of ours is one of the worst to pick for any genius : the very concept of genius has been called in question, and not only by the Maoist wing. It is, however, a fallacy to conclude that because Stockhausen isn't quite the genius he thinks he is, Wagner wasn't quite the genius he thought he was, or that Britten wasn't the genius he didn't think he was: his modesty was wellnigh Bachian. He nevertheless knew who he was, and if he or you wanted another word for it, less soiled by romantic abuse, you'd have to find it. There is all the difference in the creative world between original thought on the one hand and, on the other, both productive conventionality and that manner of originality which produces individual mannerisms. At a point in the development of composition where the latter two approaches, singly and combined, have surely gained the upper hand as never before, it is, in fact, far easier than ever before to recognise outright genius, because in our difficult compositorial situation, 'men of genius,' occasional flashes of genius, part-time originality, have virtually disappeared: nowadays you either are one or you aren't, and as always, there are precious few of you who are. To the critics, those few have traditionally stuck out like acutely sore thumbs: our own century's warning example, Schoenberg, produced a crop of historic obituaries comparable to Britten's.

He inscribed his last complete opus to me —the Third String Quartet. I hope it wasn't only (as in the case of Benjamin Frankel's last quartet) because of my knowledge of the genre but, more specifically, in view of what analytic insight [may have shown into his purely instrumental thought, which has always been underrated or mis-rated. The Times obituary drew attention to the second and third movements of the Second Quartet and wholly ignored its most stunning achievement, the sonata structure of the first movement, whose unique double exposition makes up for a lapse, indeed a lack, in the history of sonata thought: concerto apirt, the replacement of the exposition's repeat by its variation had hardly ever happened. There is only one way of repaying new thought, and that is new listening. Let us honour the dead-alive genius by not automatically concentrating, year in, year out, on the evident centre of his reputation, his vocal invention.

Previous page

Previous page